Mukti Bhawan:A Celebration Of Death, And Life

Do you know that there is really a Mukti Bhawan in Benares where old people go to die? But there is a clause that says that they can stay only for 15 days and if they do not die within that time, they will have to leave the home.

Must they really leave the home? So, what happens when suddenly one day, Dayanand Kumar (Lalit Behl) the 77-year-old retired school teacher announces to his son, daughter-in-law and grand-daughter that he has decided to go to Benares?

The family, settled in Kanpur is shocked. Rajeev (Adil Hussain) his son, who works with an insurance company, does not have a happy relationship with his father but is not really aware how much he loves and cares for the old man though they do not see eye to eye in most matters.

The family is shocked because the old man is not even prepared to wait for the marriage of his only grand-daughter just round the corner. When Rajeev says he has work to attend to, Dayanand arm-twists him emotionally him by telling him to put him in a taxi and he will go it alone.

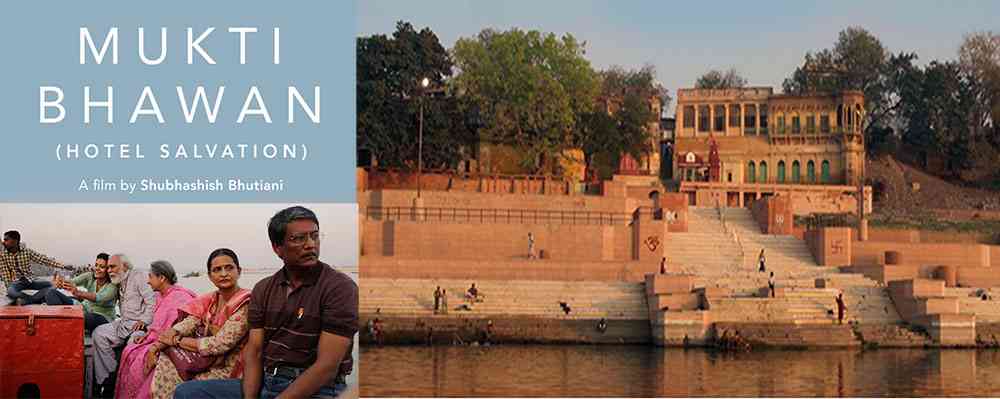

Benares, the holy city has been the backdrop of several memorable films like Rituparno Ghosh’s Chokher Bali and more recently, Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan. In Mukti Bhawan, Benares is both a city and an ideology ingrained among many Hindu men and women who are convinced that it is the only city in the world where dying can give them moksha – freedom from being ever born again, thus, ironically both defying and denying the Hindu belief in rebirth.

The concept of moksha is also found in Jainism and Buddhism. Moksha also means refers to various forms of emancipation, liberation, and release. One cannot stop wondering whether Dayanand really had been dreaming of his “time” having “come” or, whether he was using this as a plea to leave the family to its own devices and find his own salvation?

Benares is not a microcosm of the rest of the county. As presented in this film, it is a world unto itself, encapsulated within the fossilised lives of the dozens of doddering old men and women who have chosen to leave their grown children behind to redefine a new home here where they learn to live within deplorable conditions, cook their own food, get their own provisions and if they need help, they must pay for it.

But they also create their own spaces of entertainment such as watching soppy, syrupy and sentimental melodramas on the single television set, attending the daily poojas and singing bhajans and keertans together which shows that they are enjoying the very business of living and not really waiting for death.

Among them there is Vimla Mishra (Navnindra Behl) who arrived with her husband 18 years ago and stayed back when he died soon after leaving her alone. But she is not alone. She has brought her baggage of wonderful cooking, graceful hospitality and friendliness along with her, pointing out that old people waiting for death are not as depressing and as defeatist as we think they are.

The film is constantly punctuated with small touches of humour, sometimes vocal and sometimes through simple suggestion. While journeying from Kanpur to Benares in s share taxi, the cabbie picks up speed as Rajeev asks him to. But Dayanandji tell his to slow down lest he reaches “up there” before he reaches Benares!

The superstitious nature of some of the guests of Mukti Bhawan is shown through fleeting touches when an old man steps back to allow an animal to pass by, or, Dayanand striking a warm friendship with Vimla who constantly pokes him with jokes and philosophical anecdotes, offering glimpses of charm and life within these people who are supposedly waiting for death.

Dayanand adds his own touch of irony when he throws away the very bad lunch his son has cooked for him, or, complaining about the thin mattress, or, asking Rajeev to get him his regular morning glass of milk when there is no milk in the home. So off Rajeev goes to fetch milk and comes back without getting it – it is too late. “Benaras is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together” wrote Mark Twain.

But Mukti Bhawan belies this statement because the Benares we see in the film is alive and kicking and throbbing with life amidst the dying and the dead. While pyres burn on the ghats, two old men practice the pranayaam on the steps of a ghat, first Dayanand and later, his son Rajeev take a dip in the Ganges and rise up to offer Surya Pranaam.

Benares in this film is stripped of glamour and cinematographed with its crowded, labyrinthine lanes and bylanes with people crowding around, cycle rickshaws on their way to somewhere, dotted with small and big processions carrying the dead covered in zari-bordered red chunariyas moving towards the different ghats to the numerous funeral pyres in different stages of cremation.

The panoramic view of the ghats held in mid-long and long shots, the Ganges with its boats framed by the camera sometimes closing in on the faces and backs of Dayanand and Vimlaji sailing on a boat, shots of the famous evening Aarti with the river lit up with the reflections from the rotating lamps, captures the ambience of a city that is carved in history for all time.

The cinematography, with shards of light slanting in through the windows of the shabby rooms of Mukti Bhawan, the walls with the plaster peeling off, the bright pink-painted wall of Vimla Mishra’s tiny room with its own pooja corner and cooking knick knacks, a dirty mosquito net forming a veil for a weeping voice, the barely furnished office of the house reflects not only the emotional involvement of the cinematographers but also the award-worthy contribution of the art director and the careful and cautious and aesthetic vision of the editor who knows where and when to cut a scene and move on to the next one without losing out on the thread of the story at any point.

The music is low key, filled with prayers and chants and echoes of Ram Naam Satya Hai bringing the city throbbingly alive and keeping it there!

“Isn’t there a better place we can move to?” asks Rajeev and Mishra-ji, (Anil K. Rastogi the wise old caretaker and manager of Mukti Bhawan says, “Yes, there is, round the corner where you must pay Rs.500 per day,” with a poker face and toneless voice. Rajeev keeps silent because they do not have that kind of money.

During the first 15-day stay, Dayanand falls seriously ill and a concerned and tearful Rajeev thinks that the end has come. They hug each other and say “sorry” but Dayanand gets well and the father-son relationship metamorphoses in different ways. There is a purging of emotions, regrets and pains the father and son have about each other and then, slowly, thaw sets in and we see them munching peanuts on the ghats and cracking childish jokes. Dayayand says he would like to be reborn a tiger and if not, a kangaroo.

When his son asks him why a kangaroo of all things? He says that the kangaroo has pockets where he can keep his spectacles and things. Then Rajeev laughs and tells him, “then you will have to be born in Australia!” “So what, Australia it will be,” says the father to his laughing son.

While Rajeev complains that his father always bashed him up in class never mind who was the wrong-doer, Dayanand points out that Rajeev has been an authoritatian father whose daughter is terrified of him. “But I never ever beat her,” says a surprised Rajeev and Dayanand at once says, “is terror bred only through physical violence?” Rajeev’s long stay and extensions of leave puts his job in jeopardy and as father and son draw close to each other, Dayanand asks him to leave.

The acting deserves all the stars that are there in the rating hierarchy and Adil Hussain’s special Jury Mention at the recent National Awards is like a consolation prize for the one who breasted the tape in this race of excellence in performance. Lalit Behl as Dayanand, Geetanjali Kulkarni a Rajeev’s wife (remember her from Court?), Navnindra Behl as Vimla Sharma and Palomi Ghosh as Sunita, Rajeev’s daughter are no less in this performance rich film. Adil as the very frowining Rajeev who does not know what to do with his recalcitrant old father, and is shocked by the sudden rebellion in his daughter has perhaps the most challenging role of his career in this film and he could not have done better. Anil K. Rastogi as Mishra-ji is wonderful in his no-nonsense, grounded and practical approach the character demanded.

The film leaves the viewer with more questions than offers answers and many of these are uncomfortable Are these old people who retire to a waiting-for-death life in Mukti Bhawan really waiting for death to come and visit them and give them salvation?

Or, have they left their old life behind to redefine life on their own terms in their own way, with their own forms of enjoyment that can came in any form – bhajan, pranayaam, surya pranaam, watching television without others breathing down your back and hurrying you to finish off and go to bed? Did Dayanand really dream of death chasing him?

Or, did he want to turn his back on a son who was forcing his daughter to a marriage she does not want to be trapped in?

Or, was this a way to smoothen the rough edges of his relationship with his only son, knowing this was the only way to stay together for some time? All this and much more, makes Mukti Bhawan the film it has turned out to be.

One of the saddest realities of Indian cinema is that a film like Mukti Bhawan, that marks the directorial debut of 25-year-old Shubhashish Bhutani has to be plucked off Kolkata theatres within one week.

Mukti Bhawan is perhaps the most poignantly philosophical films released this year presented through a straightforward, simple narrative of an old man who thinks he is going to die, through his seemingly turbulent relationship with a caring but ever-frowning son that thaws as they struggle it out in Benares together till it is time to say goodbye.