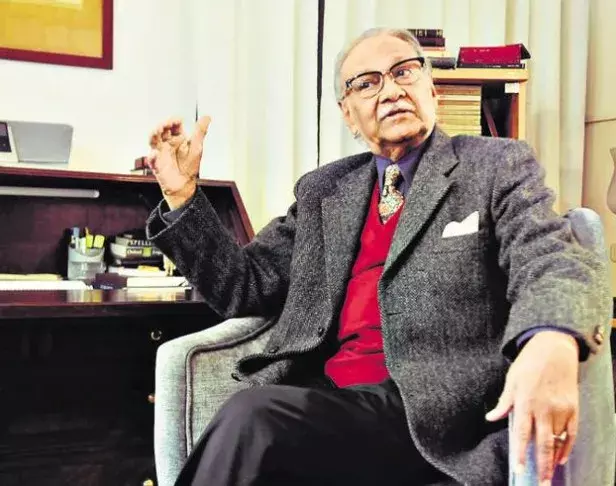

Raj Bisaria - A Cough And the Stage Came Alive

He influenced Indian theatre for over half-a-century- RIP

Once upon a time the most dramatic sound in my life was the voice. The voice that was always heard before Raj Bisaria was seen. Actually a deep cough had first announced Bisaria’s arrival even before the voice, for those waiting to learn all about the stage from him.

Those were dangerously thrilling days when the sound of a mere cough was all that was needed to make us feel alive. Bisaria had introduced us to the magic of life, on stage. I remember how hard he had struggled to make us internalise what William Shakespeare, the English playwright had said about all the world being a stage and all the men and women merely players who have their exit and their entrances and one man in his time plays many parts.

Many decades later I often catch myself skipping to the rhythm of the same tap, tap, tap sound made by the stick used by Bisaria to make walking towards his students less painful. His friends, students and admirers had helplessly watched him suffer from a bad throat, a bad back, and a not so bad love for the stage.

It is easy to use superlatives for Raj Bisaria, the great man of theatre and his bewildered, arrogant presence amongst people who seemed mediocre in comparison. For more than half-a-century, Raj Bisaria influenced theatrical activities in this part of the world.

We grew up watching the lights dim in auditoriums a thousand times before the stage was lit up to herald the start of yet another play produced, directed, and very often acted in, by the impresario in Lucknow.

The thrill of watching drama naturally led to the desire of being part of dramatic activities. Bisaria had already founded the Theatre Arts Workshop (TAW) and later he established the Bhartendu Natya Academy (BNA) now known as the Bhartendu Academy of Dramatic Arts (BADA), and its repertory. I was part of TAW, and enrolled for a course at the BNA soon after it was started in 1976. Here, I witnessed Bisaria battle to give each one of us a voice of our own.

What Bisaria has done on stage is documented. That he had introduced a modern sensibility into traditional ways of doing theatre, including folk theatre, is well acknowledged. As impresario, Bisaria’s reputation reaches far and wide. But, what else was there to him apart from theatre, is a question that had puzzled people who wanted to know him, and to love him even more.

Why was he almost harsh in real life, but endlessly hilarious in comedy performances on stage? Was Bisaria born in Lakhimpur-Kheri because his bureaucrat father was posted in the area at that time? Does he come from a family originally from a village called Bisaria, in Faridpur’s Bareilly district of Uttar Pradesh?’ When did impatience and rage begin to creep into his personality? Could it be from the moment when he lost his mother at a time that he did not want her to go?

Man-woman relationships, and how families fare with all their flaws seem of great interest to Raj Bisaria. That is why ‘Aadhe Adhure’ fascinated him. The play by Mohan Rakesh was obsessively scrutinised by Raj Bisaria who in the true spirit of the teachings of Konstantin Stanislavsky had concentrated on reading in between all the lines that were said on stage.

What was the character thinking, when he said what he had? What would the characters actually liked to say, if they could? What is that unspoken thought of the characters, is what Raj Bisaria’s theatre lessons were about.

Rakesh too was a teacher and novelist, and torch bearer of a new wave of writing. He died at the age of 47 years in 1972, and bits and pieces of what Bisaria said about ‘Aadhe Adhure’ at that time still ring fresh in memory.

It is exciting to wonder if Bisaria’s quintessentially ‘lakhnawi’ character, love for Urdu and of aesthetics can be traced back to his Kayasth ancestry? Who is not aware of how closely the community of Kayasth and Muslims had lived all over Avadh, and in Lucknow.

Their existence was a supreme example of the composite culture of the Indo-Gangetic belt that was soaked in Indo-Persian courtly etiquette. Life in Lucknow more than a century ago had combined Hindu learning with Persian literary traditions. Especially in the 19th Century, Lucknow was shaped by an urban intelligentsia that was beyond religious ghettoisation.

This is the time when Hindus and Muslims had shared state positions, celebrated each other’s holidays, borrowed from each other’s literary and artistic traditions. Europeans had entertained, and hunted with local rulers and talked, traded and intermarried in the city.

Muslim rulers were surrounded by an administration dominated by members of the Kayasth and Khatri communities.

For people of all backgrounds and from social margins everywhere Lucknow held out the promise of reinvention in its cosmopolitan embrace, writes Nasima Aziz in ‘Lucknow: Wandering in the Lanes of History’.

It is said that Lucknow became Lucknow because the rulers hunted out the best talent found in every community, irrespective of the religion and caste of citizens. For nearly a century the region of Avadh was taken care of by the most talented people from around the world.

The Kayasths were recognised for the multiple talents they possessed and were promoted as a critical link in society’s many relationships. They were made equal participants with the elite in matters of language, diet, dress, mannerisms, lifestyle and etiquette.

While they never intermarried or converted to Islam, they shared many common experiences such as primary education, and qawwali at the sufi dargah with Muslims. Shiva Das Lakhnawi, author of the popular publication Shahnama Munawwar Kalam, was an active member of the Chishti Sufi circle.

In Lucknow, the Kayasths had enjoyed positions of responsibility as ministers. Along with the ruling elite they had celebrated eid, commemorated muharram,and built imambaras.

The Persian language was used by the bureaucracy for practical purposes to earn a living but it was also a language of self-expression. In their study of the Persian language both teachers and students in Lucknow went into the depth of Persian literature and poetry, reading classics like the Bustan and Gulistan of the great Persian poet Sadi.

Another topic that begs discussion is if Bisaria’s love for drama is at all inherited from the gifted last ruler of Lucknow, Wajid Ali Shah? The most beloved entertainment of that time was the ‘mushaira’, that assembly of poets where poetry was recited till the wee hours of every morning.

The king was a poet too but he had played the sitar, he was fond of singing and he loved to dance as well. He took entertainment in mid 19th century Lucknow to Himalayan heights. In a literary culture largely dominated by the oral tradition of reciting verses, Wajid Ali Shah introduced prose and drama.

He wrote ‘Radha Kanhaiya Ka Qissa’ and staged the Rasleela, the cosmic dance of Lord Krishna. Along with Bindadin Maharaj, father of the Lucknow gharana of Kathak dance, he composed a dance drama with countless gopis, the milkmaids all madly in love with Lord Krishna.

During the performance each gopi would go into a trance, and imagine that Krishna had swirled only with her and none other. Wajid Ali Shah had made Hindu heroes converse on stage in Urdu verse and in Avadhi dialogue with Muslim princesses, and with female dancers dressed like fairies.

Ishwari Prasad Narain Singh, the Maharaja of Banaras was a patron of the Ram Leela in Banaras, the outdoor theatre performances based on the life of Lord Ram in several parts with each episode of the story staged in a different location against colourful props and settings similar to TV serials of today. In 1851, Wajid Ali Shah invited his friend Ishwari Prasad Narain Singh to be the chief guest at his performance of the musical River of Love.

Similar performances staged routinely in mid 19th Century Lucknow were a craze. Wajid Ali Shah also staged action filled romantic musical extravaganzas embracing heroes from popular Hindu mythology. The cultural trends blazed by the king were immediately imitated by the literati.

Mirza Amanat, contemporary poet composed the very popular musical drama called Inder Sabha under the patronage of Wajid Ali Shah. There is the memory of Bhartendu himself, famous as the ‘moon of India’. Born in 1850 in Banaras, Bharatendu Harishchandra was swayed by the Bengal Renaissance. He had revived interest in plays from the Puranic era and made them available in Hindi and used the new media of the printing press to influence public opinion. That the state government together with Bisaria to name Lucknow’s drama school after Bhartendu is only natural.

The legacy of Bisaria’s love for theatre is probably an extension of his profession as a teacher of English Literature at the Lucknow University. In pursuit of more, Bisaria had travelled to London to train at the British Drama League. His dream was to elevate the standard of the performing arts here to a professional level within a modern work ethic.

After having staged numerous plays by American and European writers in Lucknow, Bisaria expanded his interest to local theatre, including the art of the Nautanki. He invited the late Gulab Bai, last queen of Nautanki performances to talk to the students of BNA about her art.

Once our class was escorted by Bisaria to a night long Nautanki performance by the Great Gulab Theatre Company in the suburbs of Lucknow, of which I have no recollection. That is because one of my class fellows gave me a generous glass of thandai laced with a fat pinch of opium to drink.

That knocked me out for many hours. I had enjoyed the thandai but regret to this day to have missed a live performance of the legendary Gulab Bai.

From 1966 Bisaria had staged important plays from the West. From the early 1970s he caught up on what was being written in Hindi. He had put up an unforgettable version of Dharamvir Bharti’s ‘Andha Yug’ at the open air stage of the National Botanical Garden.

I had dreams of working with Bisaria again. During the lockdown in times of Covid, I had suggested to Bisaria that we do an online series on YouTube of conversations of love between two citizens against the spread of hate around us. He was excited. But ill health, and his suspicion of high technology prevented him from realising this dream. He passed away at the age of 89 years last week. Rest in peace Raj Bisaria.