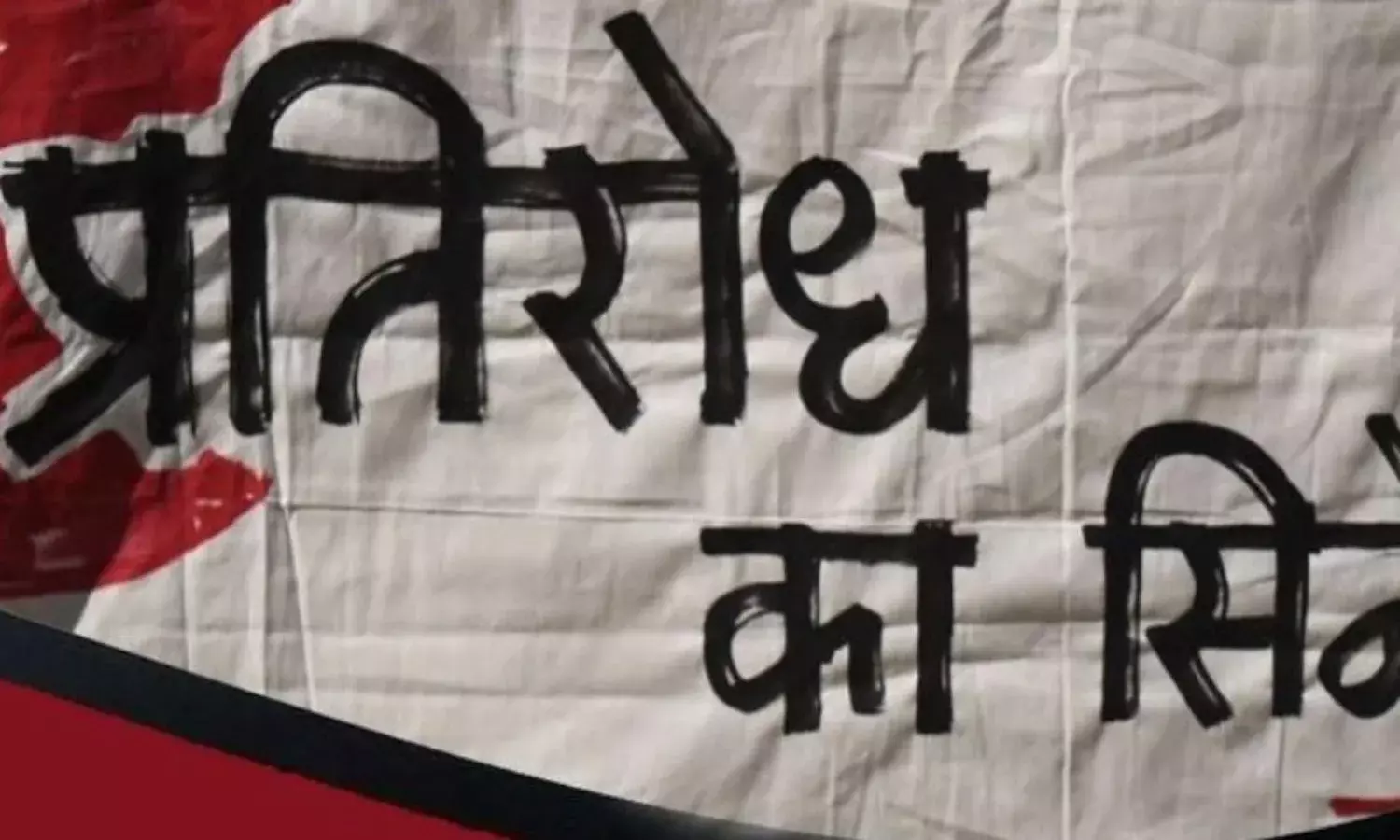

Cinema Of Resistance

In conversation with Sanjay Joshi

For many decades cinema has been a popular medium in disseminating certain ideas of the society. Acclaimed as one of its kind, National Convenor of Cinema of Resistance, Sanjay Joshi relates, in an email Interview with The Citizen, his initiative of taking independent cinema to the corners of Northern India.

What is Cinema of Resistance?

In 2005, In a meeting at Allahabad it was decided we would launch a series of film festivals. I proposed that we should focus on documentaries. There were good documentaries being made based on people’s movements and the issues of society in 80’s, 90’s and even in first decade of 21st century. With the advent of technology it became a bit easy to make documentaries, features in this decade. Documentary and screening were a possible combination. So, we decided to hold a film festival in Gorakhpur. As per the political line of Jan Sanskriti Manch, it was clear from the beginning that we would not compromise on our cultural activism. So, there was no question of corporate funding. We worked on crowdfunding and campaigned for people’s support for funds.

So, the idea generated from here that Cinema of Resistance would be a connect among people’s movement, people and cinema. Not only documentaries but also features, full length movies which speak for people would be a part of our film festivals.

Would you like to call it a movement? If so, why?

We had started screening cinema since 2006 in Gorakhpur. Now, as we are in it’s 13th year, we have successfully toured Bhilai, Azamgarh, Balia, Lucknow, Dewaria, Allahabad, Etah, Nainital, Pithoragarh, Ramnagar, Udaypur and in all small and big cities it had spread. I will not talk about big metros like Bangalore and Kolkata but in Uttar Pradesh the meaning of cinema was restricted only to Bollywood.

In these many years, through small and large screenings we have built an audience. Certainly, it is a movement in the form of a campaign. Now people call Saeed Akhtar Mirza, Nagraj Manjule, Girish Kasaravalli and their likes and contribute to the cause from their pocket. What other parameters of a movement can we expect to see? It is a continuous movement. In the coming days it has to be intensified for a larger audience exceeding the present scope of semi-urban or urban phenomenon.

What is the objective of this movement?

We want to reach to the masses through cinema as a medium. Our objective is to work as a transparent, honest, interactive, regular and non-profiting agency of communication between people and cinema by representing the real issues of people as opposed to the contemporary mainstream media and cinemas. The idea is to show a detailed picture of current socio-political concerns such as the effects of demonetization or the issues related to interstate highways and so forth through cinematic expressions.

Who are the participants?

Those who are fighting for their voices to be heard, those who want to understand and see a better society are the main participants of this initiative. When a film festival is planned we try to create a chapter for the local people who are willing to participate in this movement. The idea behind this is to create a certain understanding of cinema to the local people in terms of viewing, receiving and reciprocating about the cinema’s content. The participants vary from school students, teachers, factory workers, office clerks, university students, teachers, karmacharis, homemakers. We try and expand our reach to all sections of the society and even to kids through different kinds of film festivals.

Another segment of the participants are the filmmakers. They not only contribute by making films but also by putting in fund-money. In this initiative, the filmmakers and the audience become a major participant by sharing a stake.

How would you like to describe the journey of CoR till now?

The journey is very engaging. Till 2006, I only used to make films. Then after I concentrated on screening cinemas rather than making one. In 2018, I can say that I am not alone. With me, there are many filmmakers, social activists, researchers, painters, story writers, trade union activists and political activists.

Till now, we have been able to screen 100 feature films, 300 documentary films, 25 short and animation films, 10 lecture demonstration, 5 poetry sessions, 6 music concerts, 10 painting exhibitions, 20 Children's sections and numerous Q&A sessions. We have also premiered 14 important Indian documentaries. They are Flames of the Snow (Dir: Ashish Srivastav), In Camera (Dir: Ranjan Palit), Notes from a Global City (Dir: Surabhi Sharma), Conflict: Whose Loss Whose Gain (Debranjan Sarangi), Main Tumahara Kavi Hoon(Dir: Nitin K Pamnani), Mati ke Lal (Dir:Sanjay Kak), Red Ant Dream (Dir: Sanjay Kak), Atash (Dir: Avneesh Singh) , Milaange Baabe Ratan De Mele Te (Dir: Ajay Bhardwaj), Sawaal Ki Jarurat (Dir: Sanjay Joshi), Comrade Zia-ul-Haq (Dir: Imran and Sanjay Joshi), Chuka Bhi Nahee Hoon Main (Dir: Sanjay Joshi) , Quaid (Dir: Mohd. Gani) and Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai (Dir: Nakul Singh Sawhney).

This journey is important because of our realisation that such an initiative is crucial for the public. Not only this, but what has been exciting is that this initiative has marked in itself an importance in the gambit of independent cinema. Taking a responsibility like this can also be considered as a full time job and indeed a much needed one for anyone. I was born and brought up in Allahabad. Because of CoR I could step out of my native place and connect with people in Gorakhpur, Jaunpur, Sultanpur and many other cities. So, this journey has been very personal and exciting for me. Most importantly, in running this initiative we have not depended on any corporate agencies for any type of fund. Had we depended on big funding agencies, we would not have reached to so many people and spread the cause of people’s cinema. Now, people ask us to come to their city, they make arrangements, sometimes they do commit mistakes but learn quickly, they are now capable of organising such festivals on their own and without any big funding agencies.

What were the hurdles that you had faced during this journey?

We are working in Hindi speaking belt which is essentially a culturally backward section as compared to Bengal, Maharashtra or Kerala. Here in UP the minimum infrastructure required for screening is missing. We don’t find a space free from noise, where 100 people can sit, a dark condition can be made and projector screen can be set up. So, infrastructure has been one of the major hurdles that we have faced. Secondly, we are apprehensive about the policy level changes on guidelines of public screenings, something which may create problems for us and very much possible in this “Achhe Din wali Sarkar”. But, till now it had been a fun-filled journey. We have converted the places into temporary cinema halls, people have come to help us to install dark-room before the start of a cinema and in this way now there are quite a few cinema activists.

What do you think is the significance of such an initiative in the current socio-political scenario?

First of all, it is a less expensive medium to connect with people under the technological efficiency. When people realise that even the workers’ protests at a closed factory site can be the content of a cinema, it undergoes a cultural change. 25 years ago, you needed to go to cinema hall to watch a movie. Now, you just need a laptop and the cinema through internet, hard disk or you can watch the cinema on your mobile phone as well. The making of cinema has also become much easier with technological innovations. You can discuss with an attentive audience and invoke social issues through a cinema. I don’t think there is any other sharp tools to engage in political discussion.

The current status quoist parties use this audio visual medium the most in running fake stories, propaganda, incite riots and win elections. They are backed by big corporate funding agencies. There was a time when big cutouts of M G Ramachandran and Jayalalitha were being put up in Tamilnadu. But nowadays the more clever parties make mobile videos and invest their energy to set up mass-forwarding machinery. This technology have been used by these parties to gather votes. But this same technology can be used to question the socio-political culture as well. This is the simplest way to communicate with the people. So, I believe showing meaningful cinemas is a highly political activism.

What are the future works that you have envisaged?

The most important work for us is to make available all the positive contents in regional languages. There are many films which need to be translated in Hindi, Bengali, Oriya, Geharwali, Kumouni and other regional languages. Most of the important documentary films are in English which these people don’t understand. They still try to make out through visuals. So, for better understanding, there is a need of translation.

Anand Patwardhan, Sanjay Kak and their likes do make their works available in Hindi. Those who does their work in English, we ask for their permission and translate it into Hindi. Recently, I have translated Subrat Sahoo’s work which is based on Dam project to be implemented in Himachal Pradesh. We also provide voice over artist to the filmmakers who work on shoestring budget or no budget at all.

Secondly, we organise workshops to discuss the importance of Cinema as a medium, definition of cinema etc. Currently, we are working with school students and teachers. We also travel with cinemas to explain the development models in villages and cities. We are working on promoting independent cinema, creating a corpus for the aspiring filmmakers, to make access to equipments for screenings and other means to support independent artists.

Cultural groups and individuals have welcomed our idea of ‘No Sponsorship’ and thrust on people's funding. We are receiving proposal of starting new festivals from several small towns of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Punjab, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Odisha and Bengal. We assume that by the end of 2018 we will be coordinating with at least 15 such festivals.