Question The Rapist, Not The Victim

No one asks why he was out at night…;

In the light of the brutal rape and murder of the 31-year-old doctor studying for her post-graduate degree in respiratory medicine, it would be in the fitness of things to take an in-depth look into what leads to rape, what happens to the victim, and the political, social and emotional impact of the rape on the victim/victims, the society and the masses.

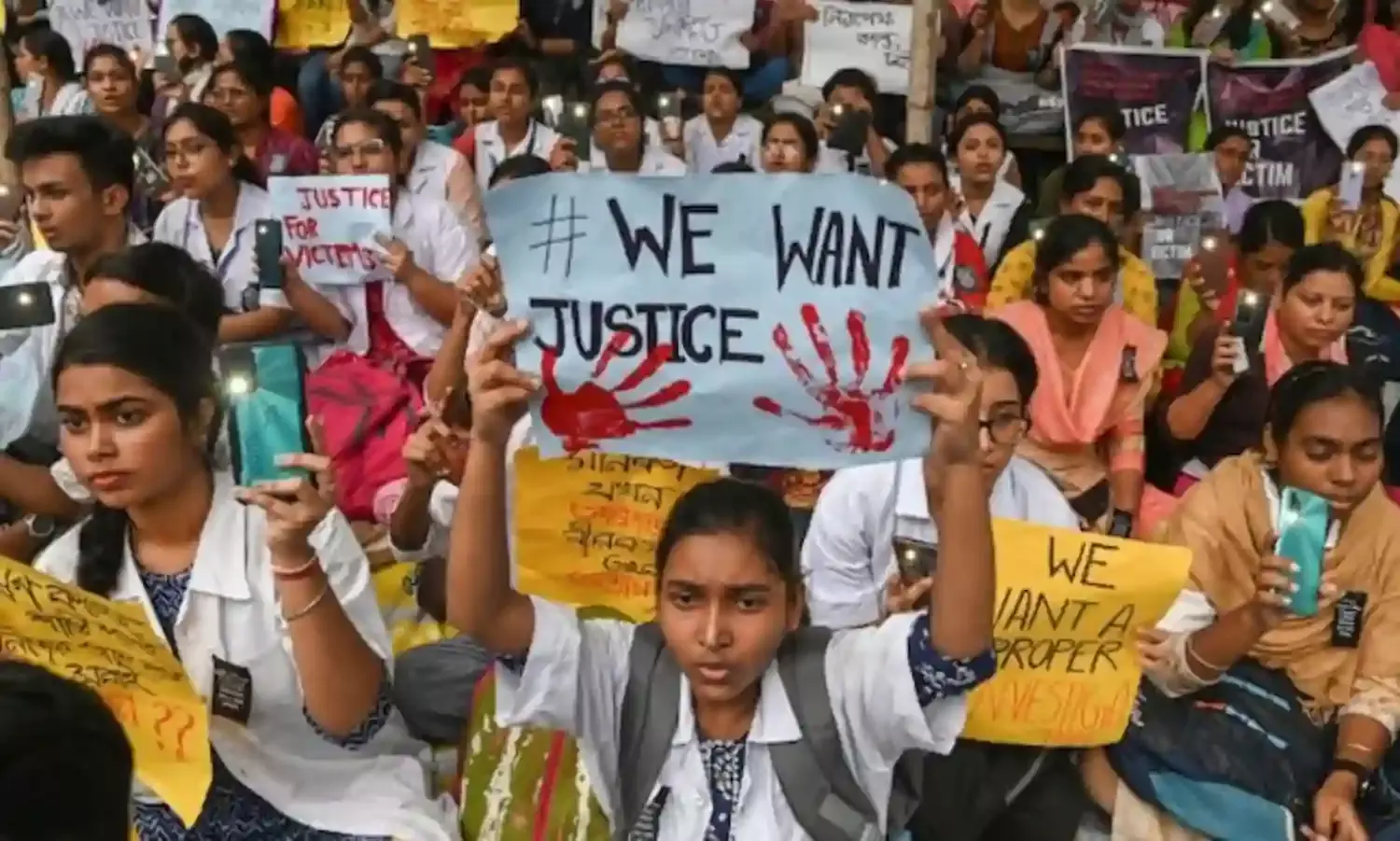

The Kolkata gang rape and brutal murder has led to a nation-wide movement by men and women across lines of caste, class, status, colour and occupation. It is perhaps because this crime is even more shocking r than Delhi’s Nirbhaya rape case.

The Kolkata doctor was gang-raped and murdered during her working hours, within the ‘safety’ of her medical hospital premises. She was on a short break, during her long hours of night duty. This proves that the brutal rape and murder has turned out to be a ‘power rape’.

Almost all cases of rapes, are power rapes, sometimes going by the acronym of “custodial rape.” Despite amendments and legal reforms, there has been little change in practice.

“All types of custodial rape” includes superintendents of remand homes, hospitals, and persons in charge at police stations with women in their custody. The issue of custodial rape is based on the power equation between the male ‘custodian’, and the female who is under his ‘custody’.

She is vulnerable to his advances as he holds ‘power’ over her. This ‘power’ can be emotional, economic, administrative, political and even legal. However, this reasoning, appears as fragile when more and more statistics of custodial rape are unfolded.

In September 1985, J, a 13-year-old girl, was gang-raped by the police who arrested her on a false charge of theft. She was a poor Dalit girl who worked as a maid. She was raped for two days though the charges against her had been withdrawn.

In March-April 1983, 19-year-old KD, a destitute of Amdug village in Bongaon, 24 Parganas, was raped by her employer Pawan Kumar Murarka for several days. Later, she was lodged in jail for 16 months while pregnant under the excuse of ‘protective custody.’

When actor Shiney Ahuja was arrested on a rape complaint lodged by his part-time domestic maid, the first thing he reportedly said to the police is that, it was consensual sex. He was echoing what hundreds of molesters and rapists have said before him.

Whenever a girl or woman in a position of subordination to a man, complains about having been sexually harassed, molested or raped by him, the first question raised is – “was it consensual”?

Then some ask, “what was she wearing? Was her behaviour and attitude appropriate? What time of the day/night was it?”

No one asks anything about the offender because patriarchy, that defines the society in which we live, is understood as man’s unjustified structural domination of women, which places a higher value on whatever is projected as male gender identity.

There is also the assumed implication that a supposedly ‘respectable man’ would not condescend to sexually abuse a ‘low-class’ woman like a maid or an official subordinate.

The Hathras gang-rape of a young Dalit girl has been preceded, and followed, by many rapes. The victims include girls raped by their family members, teachers, aquaintances, employers, ‘upper caste men’and of course strangers.

These cases also throw up the ironical reality of contemporary Hindi cinema, where ‘rape’ had once been used as a marketing strategy to draw the crowds through titillating frames. The depiction of this crime that was also used as a plot strategy to add to ‘audience pull’ has now faded almost into obscurity even in mainstream films. This was noticed even during and after the Nirbhaya rape several years ago.

In 1972, a 16-year-old girl, M, was raped at Chandrapur district, Maharashtra by four men, including two police constables. Their names were Ganpat and Tukaram.

The Sessions Court acquitted the rapists on the preposterous ground that M “had actively connived with them in the act”. The case went to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court over-ruled the High Court judgment on grounds of insufficient evidence, describing the rape as “peaceful intercourse”. The judge capitalised on the fact that the victim happened to have a boyfriend.

The judge insinuated that she was of “questionable character”. How does a girl prove that sex with a boyfriend was NOT consensual but was rape?

What right does a boyfriend, fiancé or male friend have to even touch a girl’s body without her consent? In November 1979, four lawyers challenged this judgement.

Many letters were sent to various judges, organisations and women’s groups. The Feminist Network, established in 1978, was one of the recipients of the letter.

In a meeting on the case, 11 members concluded, that a woman’s organisation be formed exclusively to combat rape. The Forum Against Rape was formed in January 1980. But M’s four rapists were never punished.

Another victim, MT, of Baghpat, Uttar Pradesh, was dragged in torn clothes through open streets to the police station for ‘investigation’. However, she was then raped there.

Rapes by people in custodial or ‘power’ positions was one of the reasons that led to the passage of the Criminal Law ‘Amendment’ Act of 1980, after three years of parliamentary inquiry and mounting public pressure. This is said to be an improvement on the previously functioning Criminal Procedure Code 1973 and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Besides increasing the amount of minimum punishment for any kind of rape from two years of rigorous imprisonment to seven years which could be stretched to life-term, one of the principal introductions was a new section called ‘Custodial Rape.’

in March 1978, RB, a young girl, was gang-raped by T. Surinder Singh, a police sub-inspector, and other policemen in Hyderabad. They also murdered her husband who was in custody of Nallakunta Police Station. But the Sessions Judge of Raichur acquitted all the accused in the case.

In response to this discriminatory judgement, the Indian Federation of Women Lawyers, the Stree Shakti Sanghatana and Vimochana, all women’s organisations, filed a petition at the Karnataka High Court.

It was placed before Justice Vittal Rao who admitted the petition on October 1, 1982. The petitioners contended that the decision of the Sessions Judge was wrong and illegal, and prayed that the same might be set right and the said persons be sentenced according to the law. The State government had also filed a separate appeal challenging the acquittal order.

According to a news report dated August 18, 2024, a minor girl from Punjab was allegedly gang raped on a public bus in Dehradun. The assault occurred at the city's inter-state bus terminus (ISBT) on her arrival from Moradabad.

The police registered a case late last night, prompting an investigation into the matter. A roadways employee has been taken into custody.

In Uttar Pradesh, a man allegedly raped his 13-year-old daughter in Amethi while he was in an inebriated state, police said. In the complaint, the victim said that she was alone at home on August 8 when she was attacked.

She lodged the police complaint on August 14 . Police said efforts were underway to nab him. The victim's mother, who had gone to her sister's place in Delhi, passed away on August 10 according to the police.

A Bengaluru Student, returning from a party was raped by a biker who gave her a lift. Police said the woman, who is a final year degree student in a city college, was returning home to Hebbagodi after a get-together in Koramangala.

Police have arrested a 69-year-old man for allegedly raping a teenage girl in Madhya Pradesh's Shahdol district, on August 14 and was reported to police the next day.

Susan Griffin, in an article published in 1971, extended Susan Brownmiller’s argument in ‘Against Her Will’, in which Brownmiller argues that the actuality and possibility of rape has served as the main agent in the “perpetuation of male domination over women by force.” to include what she calls the justification for the “male protection racket.”

With the prospect of rape lurking everywhere, a man could argue that a woman needed protection: his protection from every other man. So “each man could maintain his hold on his women by threatening her with what could be done to her, in the absence of his protection, by the rest of the men.”

No woman, it follows, should be without her “protector.” In this sense, all men benefit from rape by justifying and reinforcing their power and control over women.

Latest crime data suggests over 31,000 rape cases were reported across the country in 2021. In India, the largest number of rape victims belong to the lowest rung of the economic ladder – women driven to extremes of poverty. Or, those in a power of subordination in terms of the male superior be it an uncle, a cousin, a father, a boss, a coach, a teacher or a boss. Or, where there is a schism along casteist lines.

The Hindi-Urdu phrase for rape is ‘izzat lootna’ which literally translates as ‘robbing of honour.’ What honour? That ideology of honour that Kathleen Barry in ‘Female Sexual Slavery’ has pointed out as implicit female guilt in all sexual contact outside marriage, never mind whether it is through coercion or through self-will.

Whose honour? Not the woman’s honour, but the man in whose custody and power the woman lives and works. In ‘Against Her Will’, Susan Brownmiller argues that the actuality and possibility of rape has served as the main agent in the “perpetuation of male domination over women by force.”