“There Is No Right To Rape By Accident, To Rape By Stupidity….”

The shifting of shame;

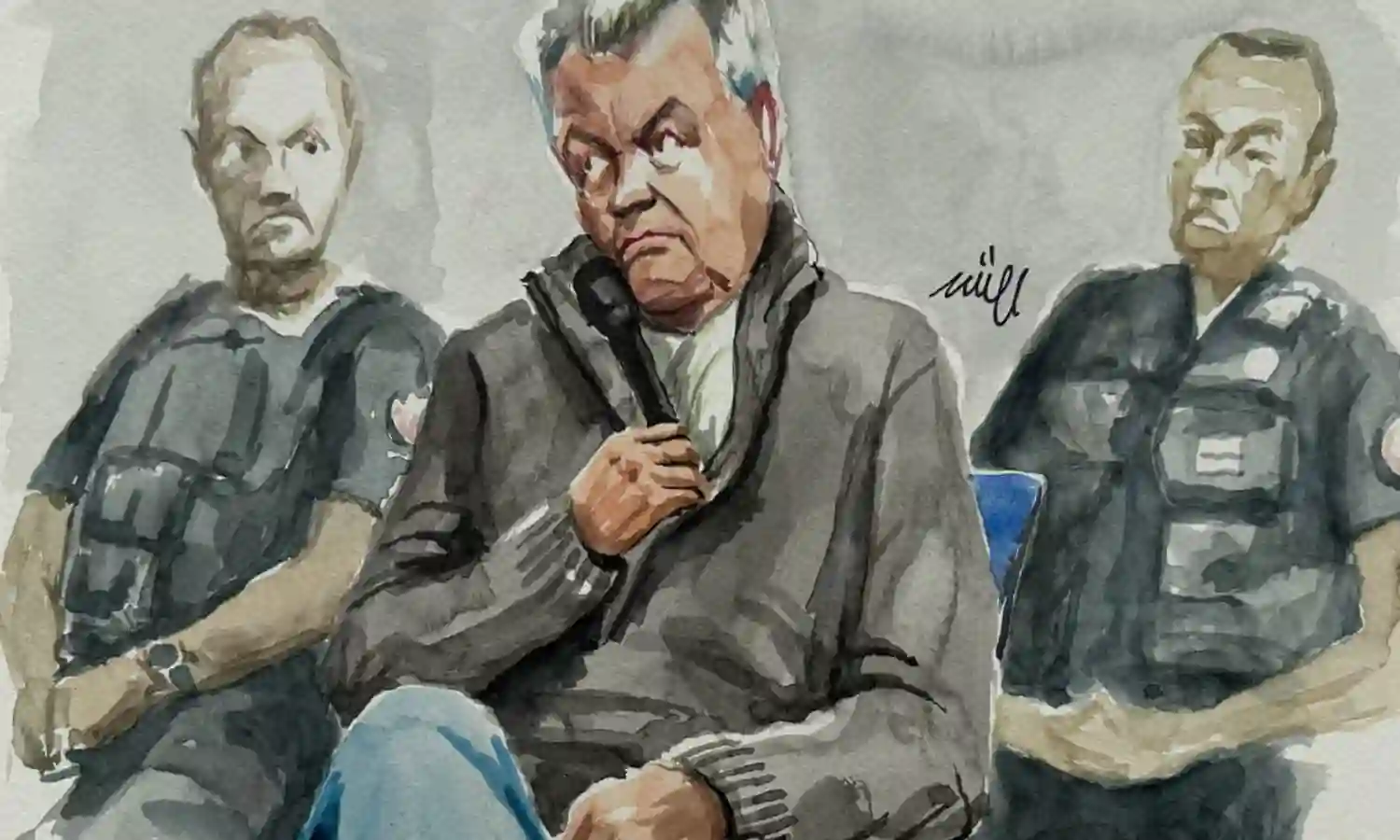

The pretty town of Avignon in southern France is known worldwide for the quaint nursery rhyme linked to the bridge that spans the river Rhone. “Sur le pont d’Avignon, On y danse: “We dance on Avignon bridge”. Last week it became notorious for another reason: the macabre case tried in its courtroom of 72 year old Dominique Pelicot and 50 others for the drugging and rape of Dominique’s wife, Gisele, over a ten year period.

The crime has sent shock waves around the globe, marking one more infamous milestone in the history of the exploitation of women. What is most memorable, however, is the astounding fortitude and courage of the victim.

Gisele, who says she is only an ordinary woman, took everyone by surprise by refusing to exercise her legal right to a trial in camera. She sat in stoic silence among strangers as the video made by her husband was played out in the open courtroom to disprove beyond doubt the ludicrous defence narratives offered by her molesters-that she was a willing participant, that they were either ignorant or had been duped, that, in the words of one rapist, he had only raped her in body, not in his mind!

“There is no right to err, to rape without intention, to rape by accident, to rape involuntarily, to rape by stupidity, to rape by lack of culture," argued Gisele’s lawyer as reported by Le Monde. The criminals had all “made a choice”. And, they were all found guilty. Dominique will spend 20 years in jail. The others will be imprisoned too for shorter periods.

Gisele abandoned the cloak of anonymity to ensure that the burden of guilt was shifted to the guilty criminals, not to the innocent victim, as is usually the case in rape cases. She has succeeded in her mission and has been admired and applauded.

Male reporters and spectators who were present in the courtroom found it impossible to deny the truth of the incriminating video or look at it for more than a few minutes. And it was the criminals, not the victim, who lowered their gaze and masked their faces as they slunk out after the sentence was pronounced.

Persons from weak groups, caught in unequal relationships, suffer the same fate as Gisele. Common decencies, like the right to consent, are denied to people of such communities. Their powerful exploiters see them only as inanimate objects and mere possessions. It is the kind of treatment meted out to children and weaker men, to slaves and servants, to peasants and “lower” castes, to civilians and conquered people, when the army marches in.

Its most pervasive manifestation is that based on gender, in the belief shared by many societies that women, who represent one half of humanity, can be used and abused with no right to consent or participation, nor even to know what is being done to them. This is the lowest form of depravity, masquerading as strength and machismo.

As Gisele’s story took over the air waves, women of all hues and countries who know and experience similar traumas assembled to thank her. Some of their reactions reinforce what we already know about objectifying and shaming victims and the ubiquity of rape in domestic settings. But, the episode has also raised new questions and pointed to fresh strategies for shaming and punishing exploiters.

Discussion of the rape problem is generally focused on saving women from dangers lurking in public places. Activists know, however, that the truth is scarier, that there are more incidents of molestation, which are rarely shared, that occur inside homes, from which victims cannot escape.

The Avignon case demonstrates how women are exploited by those whom they trust, by close family members who live with them. Many persons convicted in the Gisele episode were her neighbours and acquaintances. This is the uncomfortable fact that we prefer to ignore.

In India too, the furore that follows reports about rape is generally confined to debates about the safety of women in vehicles and on roads. Meetings are now being held by the Aam Aadmi party with women’s groups in the capital to canvass support for the Assembly elections, but they are only talking about street lights, CCTV cameras and marshalls in buses introduced over the last decade.

Is anything being done about shelters and counsellors or legal and financial support for women, who face the same dangers at home? The incident in France is a reminder of what every country hides away, how little they do to protect victims from abuse.

It is generally believed that closed-door testimonies create a helpful ambience for raped women to talk freely about their experiences and emotions. Yet, in the Gisele case, it was the open-court hearing that worked in her favour. It was this that demolished the pretexts and excuses of the rapists, who were hoping to hide from the community and shift the blame. Her decision might encourage more women to speak out in future and put the burden of guilt where it belongs-on the shoulders of criminals, instead of on innocent victims.

The judgments in the Avignon case have also provoked discussions about the concept of consent, which is at the heart of the definition of rape. French law is not based on this notion, as it only speaks of "violence, coercion, threat or surprise". Many believe that a narrow interpretation gave the accused loopholes for escaping from the charges against them. This was why they did not get longer prison sentences.

In cases of rape, there is always concern regarding the nature of the legal proof required to establish that sex has been coercive, not consensual. Not everyone agrees with the feminist argument that the statement of the victim should be taken as final, even if it is not corroborated by circumstantial evidence or oral testimony.

From the moral point of view, however, there is no ambiguity. A sexual act without the consent of a participant is always rape. Unfortunately, the need for consent is still not accepted by many societies.

Gisele’s bold stand is reminding us that rapes will continue to occur so long as women are viewed as objects, who have no right to their own choices and feelings.

Renuka Viswanathan retired from the Indian Foreign Service. The views expressed here are the writer’s own.