The Emerging Mental Health Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic

Can India cope?;

When the Covid-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the WHO it led to global policies of distancing, quarantines, travel restrictions, and cancellations of schools and large gatherings to aid in decreasing viral spread.

This has sparked perpetual worldwide fear, panic, anxiety, depression, and distress along with concern for suicide, grief, post-traumatic stress, guilt, and long term mental health disorders.

In the general public, significant anxiety is largely focused on family members and loved ones potentially contracting Covid-19, associated with female gender and student status, and is exacerbated by social media, self-quarantine, and misinformation.

Self-reported depression has increased. Other potential at risk populations include pregnant women, parents, children, the elderly, and patients with pre-existing mental health conditions such as OCD.

Medical healthcare workers have increased anxiety, depression, distress, and low sleep quality, with frontline female nurses reporting the most symptoms. PTSD, depression, grief, and guilt are of long term concern.

Future and continued studies exploring the psychiatric effects of Covid-19 worldwide are critical in understanding and treating affected populations.

The pandemic is having a significant psychological impact worldwide as evidenced by continued reports of panic and fear along with heightened anxiety and depression reported in the literature and news.

Both the Indian Psychiatric Society and American Psychiatric Association based on their surveys and research have found an increase in numbers of persons reporting negative mental health impact.

Outbreaks can affect people psychologically by precipitating new psychiatric symptoms in those without mental illness, aggravating a condition in those with pre-existing mental illness, causing distress in caregivers of affected individuals, and initiating fear, anxiety about falling sick or dying, feelings of helplessness, and blame of other people that are ill.

Altogether outbreaks can trigger or potentiate mental breakdowns. There are various psychological vulnerability factors including intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety proneness, and perceived vulnerability to disease.

There is a lack of face-to-face interactions and traditional social interactions, loss of a large sense of control, and deficiencies of adequate and accurate information.

As evidenced by previous epidemics such as the 2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and 2003 SARS outbreak, the psychological impact can outweigh the impact of the infection itself, in terms of the number and duration of people affected.

Psychiatric comorbidities including anxiety, depression, panic attacks, somatic symptom disorder, PTSD, delirium, psychosis, suicidality, and grief have been associated with previous pandemics. Therefore, it is unsurprising that anxiety, depression, PTSD, insomnia, suicide and feelings of distress have been reported in response to Covid-19.

Some anxiety and fear is healthy to motivate people to practise distancing and proper hand hygiene, but a severe amount is debilitating, and indifference puts people at risk.

Additionally, fear can drive feelings of anxiety and unease leading to irrational behaviors such as hoarding toilet paper, masks and hand sanitiser, as seen with Covid-19. It can also drive stigma, suicide, and discrimination as described against Asians, northeastern and Muslim Indians.

This is called health anxiety, caused by an idea of experiencing physical symptoms leading to potential catastrophic misinterpretations of bodily sensations and changes.

For instance, in India a 50-year-old male, described as being obsessed with watching Covid-19 media, contracted a virus which he wrongfully interpreted as Covid-19. He then quarantined himself from family and friends, threw rocks at others that approached, and hanged himself from a tree.

Unfortunately, numerous news headlines allude to increased suicide attempts and suicides worldwide in response to Covid-19. This is likely driven by panic, fear, anxiety, and depression, both in people with or without pre-existing psychiatric conditions.

However, scientific studies need to be conducted to fully understand the cause and factors behind these reported suicides. Health anxiety is a psychological factor influencing how people respond, and ultimately an index of the success or failure of public health strategies to contain the virus and keep people safe.

Other studies suggest that self-quarantine, use of social media, and a lack of credible information contribute to elevated anxiety levels.

A 14-day self-quarantine revealed that anxiety was positively associated with stress and reduced sleep quality, and, along with stress, also reduced the positive effects of social capital.

Social capital is the collection of actual or potential resources associated with a lasting network of mutual recognition, including the will to build trust, participate in community, and generate social cohesion.

In other words, by focusing on enhancing social capital, anxiety, stress, and sleep quality could be improved during periods of self-quarantine.

Furthermore, social media increased the adjusted odds ratio of anxiety compared to less social media exposure, thus identifying social media as a possible contributor to increased anxiety levels during the Covid-19 public health emergency.

Feelings of anxiety, helplessness, and uncertainty can motivate people to use remedies, false cures, and methods detrimental to their health. For instance, remedies used during the SARS coronavirus outbreak included diets of vinegar, kimchee, spicy foods, turnips and smoking cigarettes.

Perhaps Covid-19 will motivate people to turn to diet related remedies, smoking, alcohol, or even illicit substances, but more time is needed to determine this.

Additionally, during pandemics people may go to great lengths to protect themselves by displaying avoidant behavior, decontaminating objects, removing potential sources of contamination, and obsessive hand washing.

In patients with OCD, cleaning, washing, and sterilising compulsions are driven by unwanted intrusive anxiety about being dirty. Thus, fear of acquiring a new infectious disease, such as the highly contagious Covid-19, could worsen these behaviors leading to possible inhalation injuries due to overused cleaning supplies, chapped dry skin, and atopic dermatitis.

Agoraphobia—the fear or anxiety of being in situations perceived as difficult to escape or seek help for—may be exacerbated as people worry about contracting Covid-19 particularly in public areas or places without easy accessibility.

Additional groups of people at risk for developing anxiety and other mental health disorders include pregnant women, parents, and children. Infants and newborns can be infected through inhalation of viral aerosols from coughing, relatives, healthcare workers, or hospital environments.

This raises huge concerns from pregnant women worried about Covid-19 intrauterine transmission and the health of their newborn. Thus far, there is no current evidence for intrauterine infection of Covid-19 by vertical transmission in women late in pregnancy.

Similarly, health agencies report that children do not appear to have any higher risk of contracting Covid-19 than adults, but when positive children show milder symptoms. While this knowledge can help ease worry and anxiety in expecting mothers and parents, more research is needed to fully access the effects of Covid-19.

It should also be considered that many parents are now responsible for educating their children, while working from home and managing a household, or scrambling to find daycare or babysitters while schools are closed.

New changes in the environment and sudden stressors regarding children likely drive anxiety and mental health concerns in this population.

Furthermore, without school many children may not have adequate meals, resources, or a healthy environment at home to sustain them during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Additional studies could examine the psychiatric effects of Covid-19 in children including those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions.

Vicarious traumatisation (VT) describes trauma workers affected by interactions and empathic engagements with traumatised patients or patients with mental disease.

It often follows cruel and destructive disasters resulting in serious physical and mental distress due to exceeded emotional and psychological tolerance.

Interestingly, elevated VT was observed in the general public and non-frontline nurses compared to frontline nurses. This is unexpected, as higher levels of distress, anxiety, and depression were found in frontline nurses.

Perhaps frontline nurses have increased psychological endurance, or perhaps more anxiety, stress, and depression along with years of experience and medical knowledge provides a type of protection against VT.

Frontline nurses in this study had more experience and were voluntary compared to non-frontline nurses, indicating that they were likely more readily prepared and willing to handle Covid-19 trauma.

Thus, it is not entirely surprising that the general public and non-frontline nurses were more traumatised than those with training and experience.

Understanding this is important in providing appropriate mental health resources tailored toward particular populations.

Studying this phenomenon across various institutions, countries, and medical populations would be fascinating and may yield insight into the effects of trauma and patient relationships on medical workers.

The economic impact of the current pandemic is already causing havoc around the world. However the associated mental health impact is quickly rearing its ugly head. How fast can India cope?

Ashish Sarangi is a doctor of psychiatry

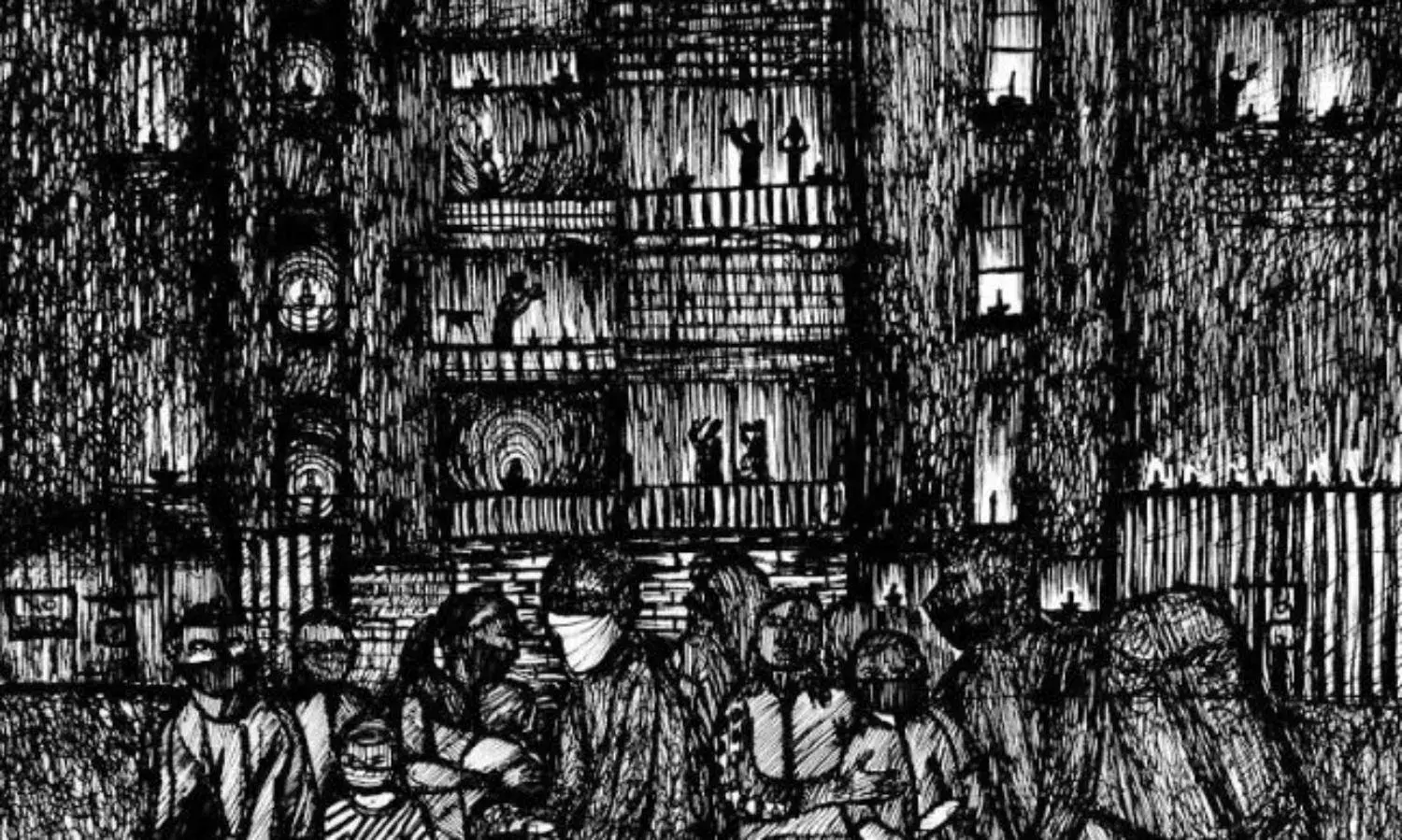

Cover Photograph Nidhin Shobhana