The Story of A Storyteller: Dastango Ramzan, A Few Firangis and Myself

Tales within a tale;

‘Huzoor, thora idhar ayenge aap? Bari inaayat hogi.’ As I was to buy a ticket to enter the Residency in Lucknow, someone very old said ‘Sir, could you please come here?’ Turning I found a man with an ancient look, in his long beard and white kurta-pyjama.

Dropping the idea of buying a ticket, I stepped towards him. He made a very strange request, the last thing I would have expected in Nawabi Lucknow. Pointing to a group of some five or six firangis – foreigners, Franks, white people – he asked me to act as an interpreter, from Lucknavi Urdu-Hindi into English.

‘Huzoor, they are from England and want to know about ancient traditions of Nawabi Lucknow. When I told them about dastangoi, they became very curious. Can you not translate, Huzoor, what I tell them? They will pay me some money too.’

But what do you know about dastangoi? How are you connected with it?

What Ramzan Ali said surprised me. At 82 he was the direct descendant of a family of dastangos who had been narrating stories to the Nawabs of Awadh since the days of Sa’adat Khan.

That was in 1722, and the capital of Awadh, then, was Faizabad. Like the Awadh Nawab Sa’adat Khan who belonged to Persia, Ramzan was also from Faizabad. Incidentally, Iran itself has a storytelling tradition spanning well over 1300 years. Rustam and Sohrab is one such gem.

(A female Dastango narrating Arabian Nights in 1911: Wikipedia )

In 1937 when Ramzan was born four days before Eid, his father Huzoor Iqbaal Khan held a great feast at Charbagh in Lucknow.

When Awadh’s capital was shifted from Faizabad to Lucknow in 1775, Nawab Asaf-ud-Doullah held a great jalsa in his royal court. In that court also, Ramzan’s ancestors were marked by their presence.

In fact, even a hundred years ago, open-air storytelling by men and women would be held regularly in different parts of Lucknow, Rampur and Delhi.

For curiosity’s sake, I asked Ramzan if he had a good stock of stories. He said he had forgotten a large number of the stories he inherited from his Ammi Jaan and Abba Huzoor. However, he still remembers two or three.

Suddenly, the angry words of Khurshid – our very own Shabana Azmi – in Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi flashed before my eyes. The begum of Mirza Sajjad Ali – our very own Sanjeev Kumar – Khurshid is cursing shatranj or chess as it keeps her husband always busy. To top her misery, Hiria the storyteller – our very lovely Leela Mishra – does not remember many stories. She has a stock of only three stories that she narrates every day. She has forgotten the rest.

Sitting under a tree adjacent to the ticket counter of Residency, Ramzan beckoned to the firangis who came forward eagerly. They asked about the oral tradition of telling stories that originated in Arabia. They were particularly interested to know if firangis like them would also listen to such stories from dastangos.

The firangi crowd grew extremely curious upon learning that Ramzan’s ancestors used to narrate dastans or stories to their ancestors in the Residency from 1722 right up to 1857, when the Sepoy Mutiny took place.

He explained to them that after Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was exiled to Calcutta in 1856, at least 82 storytelling families left Lucknow for Calcutta.

The firangi engineers of the Indian Railways who were building the Charbag Railway Station in 1867 also were told stories in the evenings, by his great-grandfather Dastango Ilahi Baksh Khan.

He told them that when the great Sufi pir Nizamuddin Aulia had fallen ill in Delhi, his chief disciple Amir Khusrow would narrate the stories of Qissa-e-Chahar Darvesh or The Tale of Four Dervishes to him. Believe it not, the saint recovered after listening to those ancient dastans.

Ramzan’s style of narration was intoxicating, and the firangis seemed to have been opiated. I too was most surprised to know that the hundreds of opium dens that existed in Lucknow before 1920, employed dastangos on a monthly retainer, to recite tales to afimchis or opium addicts.

Those opium dens dotted different parts of Lucknow including Chowk, Charbagh, Alamganj, Nakhas, Aminabad and near Rumi Darwaza.

Just as Emperor Akbar and other Mughal rulers had patronised this art, all the Awadh Nawabs too kept story tellers in their courts. This gave a major impetus to Urdu literature after 1754, during the rule of Nawab Shuja-ud-Doullah. The storytellers needed new stories and their stock of tales needed renewing.

In fact, Urdu literature owes a lot to these dastans. A dastango couldn’t go on repeating stories from the Thousand and One Nights or Shirin Farhad.

(Rumi Darwaza of Lucknow: in the past this used to be a major place of Dastangos)

It is here that we find the irritation of Khurshid Begum of Shatranj Ke Khiladi, and for good reason. Her storyteller, the old lady Hiria had forgotten all the old stories and couldn’t come up with anything new, or wouldn’t.

Meanwhile, Ramzan was asked by one of the firangis if there were any British in Lucknow who learnt Dastangoi and earned fame for it. There was indeed such a sahib in Lucknow who earned notoriety as a dastango, but no fame at all.

This sahib-dastango performed during the rule of Nawab Yamin-ud-Doulla in 1798, and he was considered a mad by the officers of the Residency. Ramzan does not remember his name.

He was a clerk in the opium godown at Alamganj in Lucknow, Ramzan retold, who took a terrible fancy to the stories – mostly bad – about Warren Hastings, who as Governor-General of India from 1773 to 1785 oppressed the people of Lucknow, Benaras, Allahabad and Kanpur so much that they coined a lyrical limerick:

‘Haathi par howda, aur ghore par jin

Jaldi bhago, jaldi bhago Warren Hastings’

(Saddle your horse and prepare your elephant - Get the hell out of here Warren Hastings.)

The opium clerk also came to know that kala aadmi or black man or the native believed that firangis were born from the eggs of chickens, pigeons and ducks. That is why they were so white: ‘Ande se nikla firangi gora…’

On hearing my translations, the firangis had a hearty laugh. They offered Ramzan some money. And I, abandoning my desire to enter the Residency, asked Ramzan to take me to his 210-year-old house in Charbagh. I was curious to know more about him.

When we reached his home located in a very narrow lane lined with houses that probably date back to the days when the capital of Awadh was shifted from Faizabad to Lucknow, he shouted for his son Yusuf to bring me a cup of tea.

The story of this storyteller is really tragic. Ramzan’s only daughter, Amina, was killed in a riot in Meerut together with her husband. His wife died as a cancer patient. Now his son was insisting on selling the house and heading to Saudi Arabia or Oman.

But Ramzan would not sell the house. Serving us tea, Yusuf admonished him: ‘As soon as you die, I will sell the house and leave the country.’

Some eight of nine months later, I visited Lucknow again on tour. The first thing I did was to return to that narrow lane in Charbagh where Ramzan lived. As I reached the door of his ancient house, I found that quite a few people had gathered there. I asked what had happened?

Ramzan Mian, the Dastango, is dead and we are carrying his body to the grave!

Yusuf is now free. He can sell the house and fly to Oman or Saudi Arabia.

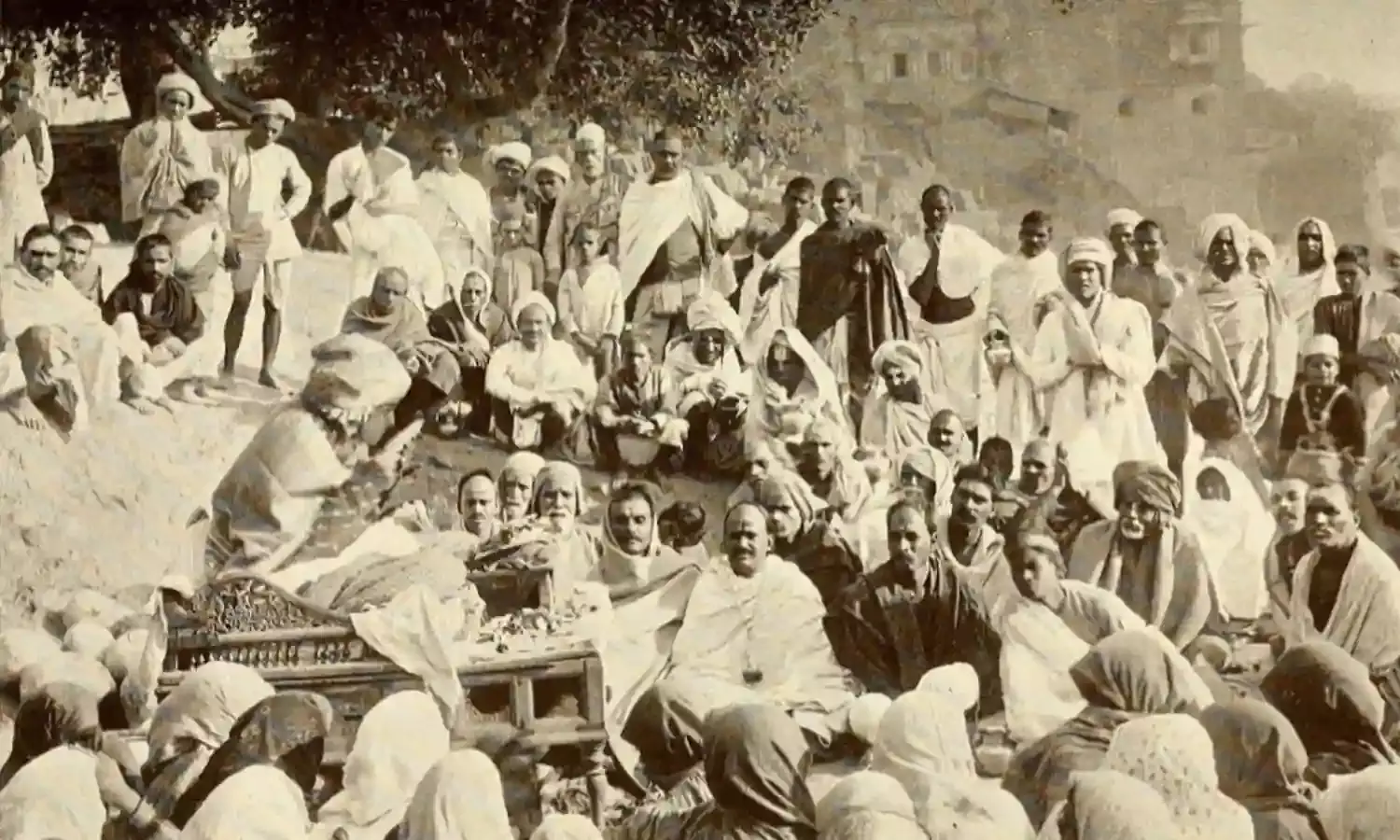

(A Dastango reciting epics among villagers in 1913: Wikipedia)