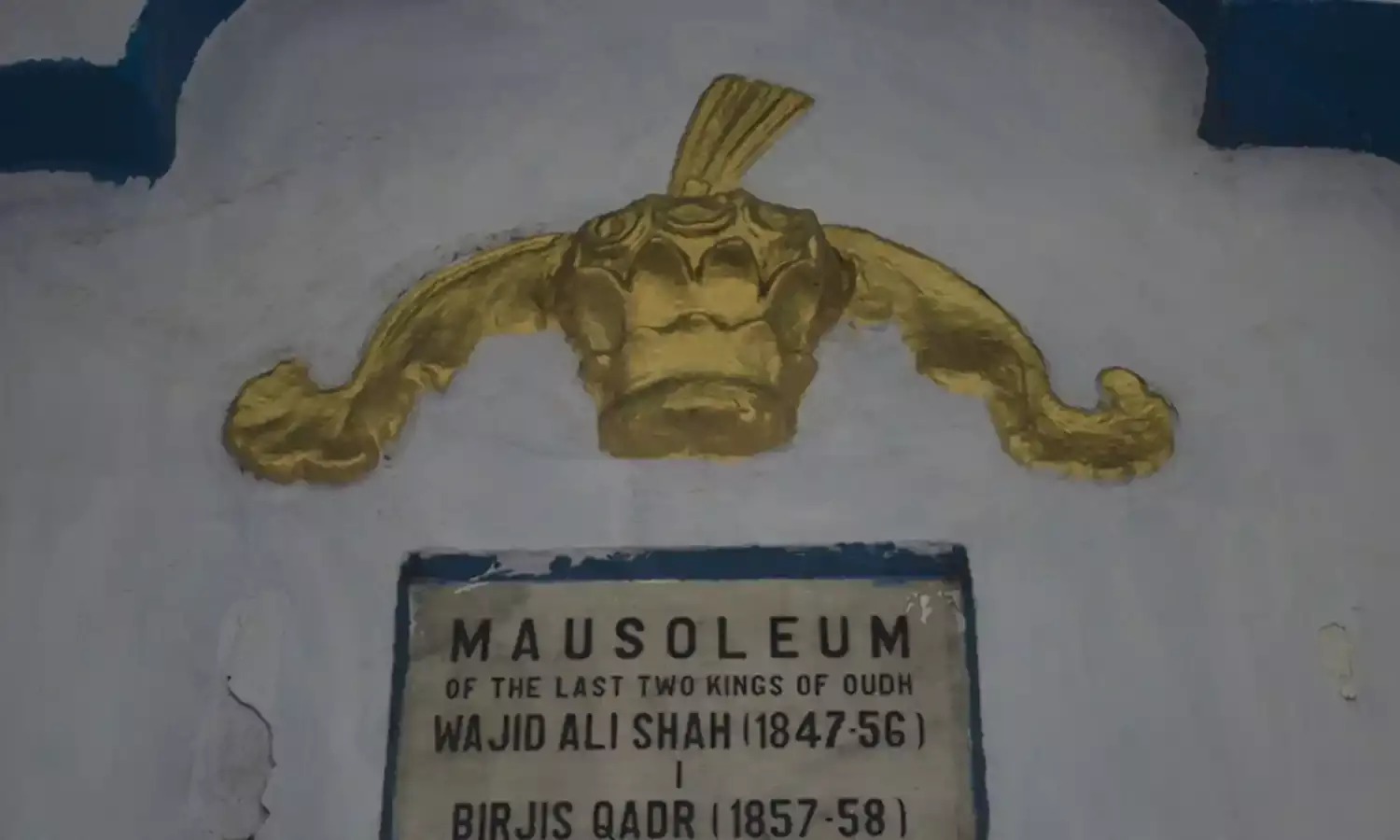

As yellow-ochre rays of the new born sun illuminated the Sibtainabad Imambara, I stepped through its gate toward the tomb of Wajid Ali Shah, Nawab of Oudh and musical Badshah of Hindustan.

I have almost made it my practice to visit the imambara, located at Metiabruz in Kolkata, whenever I am in the city. Built in 1864, it is a replica of Lucknow’s Bada Imambara.

I moved gently towards the eastern side of its main hall where the tomb of Wajid Ali Shah lies.

But my feet suddenly froze.

Somebody is humming an immortal song in Bhairavi, “Babul Mora Naihar Chuto Hi Jaye…”

Since childhood I have heard the song hundreds of times, yet I feel as if the words and its sur or tunefulness are entering my ears for the first time, to calm my brain and soothe my heart.

Who could the singer be?

Extremely curious, I tiptoed toward the source…

And I found it!

Closing his eyes and reclining against the imambara wall, just a few feet from Wajid Ali Shah’s final resting place, a man no older than 18 was humming the song.

Wearing a white pyjama and milky kurta in the Lucknowi style, he appeared submerged in the raag. He did not know I stood before him. I stood still to allow him to complete the song. But suddenly he stopped. Maybe his senses said someone was standing before him?

Salam Walekum!

Walekum Salam! I replied. What is your name?

Ali Ashraf, Janab!

Ashraf, your voice is very melodious.

Nahi, Hazrat! Yeh Gana Hi Aisa Hai to Jo Aapke Gale Ko Surila Bana Deta Hai… Please do not credit my voice, credit this song. It automatically makes the voice of the singer melodious.

The young man was absolutely right. This gem in Bhairavi is such that it adds a honeyed touch to its singer.

How strange that its composer, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, was dubbed by the East India Company a “failure as a ruler” yet he ruled over Hindustan culturally adding new dimensions to its world.

Huzoor! Hind me to Sikandar bhi aya, Nadir bhi aya, par koi rah na gaya… In this country, lots of kings successfully invaded and won. But their names are not being remembered by people.

Aap Rangeele Nawab aur Zafar Badshah ko le lo, hum aaj bhi unhe zinda rakkhe hai unke gane ke saath. Take two Mughal kings Muhammad Shah and Bahadur Shah – we are alive through their songs.

Had Ashraf read my mind?

In fact, a question always puzzles me whenever I come to the mausoleum of any ruler marked by controversy, or those who failed to make a mark in their role as ruler. This list is not long but their contribution to Hindustani music and culture is tremendous.

Take Wajid Ali Shah, Jahandar Shah, Muhammad Shah Rangeela or Bahadur Shah Zafar. Hindustan was ruled by hundreds of Badshahs and attacked by such mighty persons as Alexander and Nadir Shah.

We hardly utter their names despite the fact that they were great warriors and successful rulers. But there hardly is a day when songs of the failed badshahs like Wajid Ali Shah, Jahandar Shah, Muhammad Shah Rangeela or Bahadiur Shah Zafar are not hummed or sung with heart.

Alexander, Nadir Shah or hundreds of able rulers are lost in the passages of time but not these four failure rulers. Another very puzzling fact is that two other rulers we consider controversial, Allauddin Khilji and Firoz Shah Tughlaq, played most crucial roles in developing Hindustani music.

Is it that the realm of music is not for traditional rulers who are too mundane? Is it that they were mundane but in some recesses of their mind were philosophical in nature?

In fact, unless you are metaphysical or ethereal by birth, Ragas, Raginis, Ghazal or musical rhythms cannot perhaps interact with your body chemistry.

Before we take this up, let us know Ali Ashraf a bit better.

Son of a Persian scholar father and a classical singer mother, Ashraf received the gift of Ragas, Raginis as a matter of birth and bearing. His ancestors, all experts in Lucknowi Gharana of Kathak and classical Hindustani Ragas, migrated to Calcutta from Lucknow way back in 1858.

Only a year ago, all Oudh in today’s Uttar Pradesh had surrendered itself to the conflagration of the Sepoy Mutiny. Ashraf’s ancestors fled from one place to another to escape the dragnet of the East India Company.

They fought in the Mutiny for Begum Hazrat Mahal against Kampani Bahadur: the British East India Company.

It was over a year’s Odyssey escaping from Oudh, hiding in jungles, fording rivers and finally reaching the French colony of Chandernagore (today’s Chandannagar) some 40 km away from the Imperial British capital Calcutta.

Chandernagore in those days acted as a temporary shelter to the mutineers of Lucknow, Benaras, Cawnpore, Allahabad, Patna and other hotspots of the Ghadar or Sepoy Mutiny, as Kampani Bahadur launched a massive search for those who had fought for Begum Hazrat Mahal, wife of Wajid Ali Shah and Queen of Awadh.

Usually, those fugitives would stay inside French territory as the British could not arrest them there. Ali Ashraf’s ancestors also stayed there for a few months and started reaching Metiabruz in Calcutta clandestinely one by one.

The process took several months.

Although the French colony was very safe, the singers, musicians, baijis and dancers who participated in the Ghadar of 1857 in Oudh had no future there. The reason being the French, unlike the British, had little interest in Hindustani classical music or dance.

Hence, moving out to Calcutta was a professional necessity for them. So Ali Ashraf’s family moved to Metiabruz.

An interesting fact about the sociocultural milieu of Bengal of 18th and 19th century Bengal is that political troubles in Delhi, Agra, Oudh, Bundelkhand, Baghelkhand, Nagpur, Gwalior and Dharwad (in today’s Karnataka) greatly helped it to grow.

All these places became extremely disturbed with the decline of Mughal power.

Frequent wars, political murders, conspiracies in corridors of power, revolts or factional infighting that began among the Mughal claimants to the throne of Delhi after the death of Aurangzeb Alamgir in 1707 came as a boon for Bengali culture.

Cities like Dhaka, Bhawal, Rajshahi and Jessore (now in Bangladesh), Murshidabad, Burdwan and Coochbehar started attracting singers, musicians and dancers from trouble-torn pockets after the time of the Mughal king Jahandar Shah, himself a great artist and patron of art, music, dance and literature.

At that time, Calcutta was not even born. Its existence was restricted to three small villages: Govindapur, Sutanuti and Kalikata. After it became the capital of East India Company in 1772, the town started attracting musical talents.

Those were the days of Kalawants of the northern and central parts of Hindustan. Kalawants, classical singers, poets and lyricists, drummers and musicians, played the most dominant roles in shaping different raags and gharanas. They also popularised the forms of raags and raginis that are now well known.

Traditionally and by sentiment, Kalawants hated war, skirmish, revolts, uprisings or political disturbance. That is why they were one of the most migratory communities of Hindustan in those days, as they would leave a disturbed place to move to another where peace existed.

A Strange Coincidence…

At a young age, Ali Ashraf seems to know much about the history of Hindustani classical Gayaki. He offered me a very important story idea and also the scope to research it. This is the strange coincidence, of three Mughal shahs and one badshah, who were all connoisseurs of the classical Hindustani gharanas of music and dance.

They all failed as effective political rulers. But they are the crown jewels of Hindustani classical music. No successful emperor or ruler can match them in this field. In their defeat as rulers, they succeeded in ruling people’s hearts and minds.

Taking Ashraf’s advice, I indulged in knowing Jehandar Shah more closely.

As British historians taught us, he may have been leading a life of whims, fancies and frivolity with his favourite wife Lal Kunwar, a descendant of Mian Tansen of the Court of Emperor Akbar, but his contributions in the field of music, dance and art just cannot be minimised.

Jahandar Shah was a man of contradictions. One often wonders, how could he submerge himself in sangeet while waging pitched battles and weaving conspiracies against his relatives out to grab Delhi’s Masnad?

Received Mughal history dubs Jahandar Shah as the “Lord of Misrule” but it was he who is still praised by many for holding evening programmes of song and dance at the Diwan-i-Khas in Delhi’s Lal Qila.

Like a sad song, his life came to an end on February 11, 1713 when professional stranglers squeezed the life out of his body. He was defeated by Farrukhsiyar and put to death. That was the end of his journey.

Then there is the other Mughal Badshah marked by failures who yet succeeded stupendously in music and dance, Muhammad Shah Rangeela.

Rangeela Badshah should also be saluted for promoting what we call Urdu. In fact, Urdu owes its growth to this Sultan who was defeated by Nadir Shah, who may have been a successful warrior but no Delhi-wallah would like to utter his name for the massacre he perpetrated in the city.

But every day, some musical channel or the other plays tunes to this song of Rangeela Nawab set in Miyan Ki Malhar:

mohammad shah rangeele re

sajna

tum bin main ka

ab din ratiyaan

kachhu na suhaawe

mohammad shah rangeele re…

Who says he was a failure? Not the Shairs of Urdu, of course.

Rangeela Nawab is said to have converted Urdu into the language of the Mughal Court in Delhi, promoting it as a lyrical language of Sher-o-Shairi. In fact, he had also invited “the first Urdu Shayar” Wali Dakani to his court.

And Muhammad Shah Rangeela not only popularised qawwali but also made several reforms in kathak dance. He was also instrumental in shaping khayal singing, which still runs almost the same. For this he is said to share the credit with Naimat Khan, Sadarang, Feroz Khan Adarang…

Rangila Badshah’s last days were tragic. After the defeat of the Mughal army in battle, he suffered terrible mental trauma and kept himself in a room after bolting it from inside. On April 26, 1748 his journey came to an end.

Similarly, the Mughal Badhshah Bahadur Shah Zafar is also considered a failure. But was he? No! He still rules our heart. He added a new dimension to the Urdu Ghazal. Defeated in war in 1857, the East India Company exiled him to Burma where he died on November 7, 1862.

Zafar Badshah is dead, long live Bahadur Shah. Otherwise, why would we still be humming:

Na kisi ki aankh ka noor hoon

na kisi ke dil ka qaraar hoon

jo kisi ke kaam na aa sake

main wo ek musht-i-gubaar hoon…

Coming back to Wajid Ali Shah, we find the same story. He failed as a successful ruler yet has ruled our hearts for well over a century since his inteqaal in Calcutta on September 1, 1887.

Still we hum his Babul Mora…