Unity is a Good Thing, but Unity in Subjection?

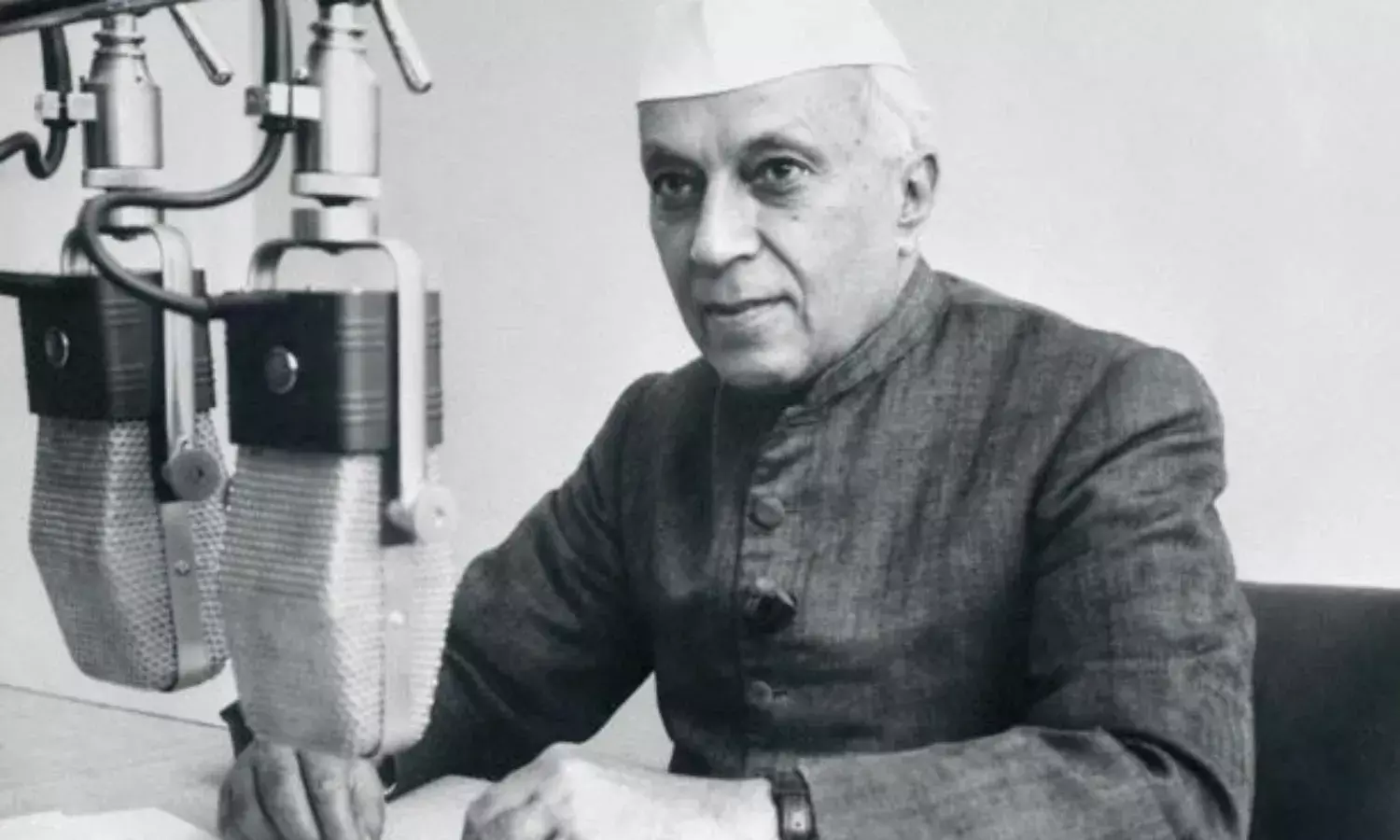

Remembering Jawaharlal Nehru (1889'1964);

Naked coercion, as India was experiencing, is an expensive affair for the rulers. Even for them it is a painful and nerve-shaking ordeal, and they know well that ultimately it weakens their foundations. It exposes continually the real character of their rule, both to the people coerced and the world at large.

They infinitely prefer to put on the velvet glove to hide the iron fist. Nothing is more irritating and, in the final analysis, harmful to a Government than to have to deal with people who will not bend to its will, whatever the consequences. So even sporadic defiance of the repressive measures had value; it strengthened the people and sapped the morale of Government…

The British conception of ruling India was the police conception of the State. Government’s job was to protect the State and leave the rest to others. Their public finance dealt with military expenditure, police, civil administration, interest on debt. The economic needs of the citizens were not looked after, and were sacrificed to British interests. The cultural and other needs of the people, except for a tiny handful, were routinely neglected.

The changing conceptions of public finance which brought free and universal education, improvement of public health, care of poor and feeble-minded, insurance of workers against illness, old age and unemployment, etc., in other countries, were almost beyond the ken of the Government.

It could not indulge in these spending activities for its tax system was most regressive, taking a much larger proportion of small incomes than of the larger ones, and its expenditure on its protective and administrative functions was terribly heavy and swallowed up most of the revenue.

The outstanding feature of British rule was their concentration on everything that went to strengthen their political and economic hold on the country. Everything else was incidental.

If they built up a powerful central government and an efficient police force, that was an achievement for which they can take credit, but the Indian people can hardly congratulate themselves on it.

Unity is a good thing, but unity in subjection is hardly a thing to be proud of. The very strength of a despotic government may become a greater burden for a people; and a police force, no doubt useful in many ways, can be, and has been often enough, turned against the very people it is supposed to protect…

An authoritarian system of government, and especially one that is foreign, must encourage a psychology of subservience and try to limit the mental outlook and horizon of the people. It must crush much that is finest in youth—enterprise, spirit of adventure, originality, ‘pep’—and encourage sneakishness, rigid conformity, and a desire to cringe and please the bosses…

But that is because the whole system has been built this way, and the subordinates are not by any means the best men, nor have they ever been made to shoulder responsibility. I feel convinced that there is abundant good material in India, and it could be available within a fairly short period of time if proper steps were taken.

But that means a complete change in our governmental and social outlook. It means a new State.

As it is we are told that whatever changes in the constitutional apparatus may come our way, the rigid framework of the great services which guard and shelter us will continue as before. Hierophants of the sacred mysteries of government, they will guard the temple and prevent the vulgar from entering its holy precincts.

Gradually, as we make ourselves worthy of the privilege, they will remove the veils one after another, till, in some future age, even the holy of holies stands uncovered to our wandering and reverent eyes.

Of all these imperial services the Indian Civil Service holds first place, and to it must largely go the credit or discredit for the functioning of government in India.

We have been frequently told of the many virtues of this service, and its greatness in the imperial scheme has almost become a maxim. Its unchallenged position of authority in India with the almost autocratic power that this gives, as well as the praise and boosting which it receives in ample measure, cannot be wholly good for the mental equilibrium of any individual or group.

With all my admiration for the Service, I am afraid I must admit that it is peculiarly susceptible, both individually and as a whole, to that old and yet somewhat modern disease, paranoia.

It would be idle to deny the good qualities of the I.C.S., for we are not allowed to forget them, but so much bunkum has been and is said about te Service that I sometimes feel a little debunking would be desirable…

If its ability and efficiency are to be measured from the point of view of strengthening the British Empire in India and helping it to exploit the country, the I.C.S. may certainly claim to have done well.

If, however, the test is the well-being of the Indian masses, they have signally failed, and their failure becomes even more noticeable when one sees the enormous distance that separates them in regard to income and standards of living from the masses they are meant to serve, and from whom ultimately their varied emoluments come.

Trained and circumstanced as they were, they could only act in that way.

Because they were few in numbers, surrounded by an alien and often unfriendly people, they held together and kept up a certain standard. The prestige both of race and office demanded this.

And because they had largely autocratic powers, they resented all criticism, considered it one of the major sins, became more and more intolerant and pedagogic, and developed many of the failings of irresponsible rulers.

They were self-satisfied and self-sufficient, narrow and fixed minds, static in a changing world, and wholly unsuited to a progressive environment.

When abler and more adaptable minds than theirs tackled the Indian problem they resented this, called them offensive names, suppressed them and threw every possible obstacle in their way. And when post-war changes brought dynamic conditions, they were wholly at sea and unable to adapt themselves to them.

Their limited hidebound education had not fitted them for such emergencies and novel situations. They had been spoilt by a long spell of irresponsibility…

The underlying assumption of the I.C.S. is that they discharge their duties most efficiently, and therefore they can lay every stress on their claims, and the claims are many and varied. If India is poor, that is the fault of her social customs, her banias and money-lenders, and above all, her enormous population.

The greatest bania of all, the British Government in India, is conveniently ignored…

But this argument of over-population is deserving of further notice. The problem today all over the world is not one of lack of food or lack of other essentials, but actually lack of mouths to feed, or, to put it differently, lack of capacity to buy food, etc., for those who are in need. Even in India, considered apart, there is no lack of food, and though the population has gone up, the food supply has increased and can increase more proportionately than the population…

But of one thing I am quite sure, that no new order can be built up in India so long as the spirit of the I.C.S. pervades our administration and our public services. That spirit of authoritarianism is the ally of imperialism, and it cannot co-exist with freedom. It will either succeed in crushing freedom or will be swept away itself.

Only with one type of state is it likely to fit in, and that is the fascist type…

There is a great deal of talk of safeguards in these days of constitution-making. If these safeguards are to be in the interests of India, they should lay down, among other things, that the I.C.S. and similar services should cease to exist in their present form and with the powers and privileges they possess, and should have nothing to do with the new constitution.

Even more mysterious and formidable are the so-called Defence Services. We may not criticize them, we may not say anything about them, for what do we know about such matters? We must only pay and pay heavily without murmuring…

It is, of course, an impertinence for a layman to argue about military affairs with a Commander-in-Chief, and yet perhaps even an armchair critic might be permitted to make a few observations.

It is conceivable that the interests of those who hold the Empire by the sword and those over whose heads this shining weapon ever hangs, might differ. It is possible that an Indian army might be made to serve Indian interests or to serve imperial interests, and the two might differ or even conflict with each other.

A politician and an armchair critic might also wonder if the claims of eminent generals for freedom from interference are valid after the experiences of the World War. They had a free field then to a large extent, and from all accounts they made a terrible mess of almost everything in every army—British, French, German, Austrian, Italian, Russian…

Politicians, like all other people, err frequently, but democratic politicians have to be sensitive and responsive to men and events, and they usually realize their mistakes and try to repair them. The soldier is bred in a different atmosphere, where authority reigns and criticism is not tolerated. So he resents the advice of others and when he errs, he errs thoroughly and persists in error. For him the chin is more important than the mind or brain.

In India we have the advantage of having produced a mixed type, for the civil administration itself has grown up and lives in a semi-military atmosphere of authority and self-sufficiency, and possesses therefore to a great extent the soldier’s chin and other virtues…

We have now a military academy at Dehra Dun where gentlemen cadets are trained to become officers. They are very smart on parade, we are told, and they will no doubt make admirable officers.

But I wonder sometimes what purpose this training serves, unless it is accompanied by technical training. Infantry and cavalry are about as much use today as the Roman phalanx, and the rifle is little better than a bow and arrow in an age of air warfare, gas bombs, tanks, and powerful artillery. No doubt their trainers and mentors realize this…

What is our objective: a peasant State or an industrial one? Of course we are bound to remain predominantly agricultural, but one can and, I think, must push on industry.

Our captains of industry are quite amazingly backward in their ideas; they are not even up-to-date capitalists. The masses are so poor that they do not look upon them as potential consumers, and fight bitterly against any proposal to increase wages or lower hours of work…

To talk of improving these staggering conditions by philanthropy or local efforts in rural uplift is a mockery of the peasant and his misery.

How are we to get out of this quagmire? Means can no doubt be devised, although it is a difficult task to raise masses of people who have sunk so low. But the real difficulty comes from interested groups who oppose change, and under imperialist domination the change seems to be out of the question.

In what direction will India look in the coming years? Communism and fascism seem to be the major tendencies of the age, and intermediate tendencies and vacillating groups are gradually being eliminated…

There are already clearly marked fascist tendencies in India’s young men and women, especially in Bengal, but to some extent in every province, and the Congress is beginning to reflect them.

Because of fascism’s close connection with extreme forms of violence, the elders of the Congress, wedded as they are to non-violence, have a natural horror of it.

But the so-called philosophical background of fascism—the Corporate State with private property preserved and vested interests curbed but not done away with—will probably appeal to them. It seems to be at first sight a golden way of retaining the old and yet having the new. Whether it is possible to both have the cake and eat it is another matter.

But the real drive towards fascism will naturally come from the younger members of the middle class.

Actually, at present, it is part of the middle class in India that is revolutionary, not so much the workers or the peasantry, though no doubt the industrial workers are potentially more so. This nationalist middle class is a favourable field for the spread of fascist ideas.

But fascism cannot spread here in the European sense so long as there is a foreign government. Indian fascism must necessarily stand for Indian independence, and cannot therefore ally itself with British imperialism. It will have to seek support from the masses.

If British control were wholly removed, fascism would probably grow rapidly, supported as it would certainly be by the upper middle class and the vested interests…

I write vaguely and somewhat academically about current events, and try to play the part of a detached onlooker… What would I do now? What would I suggest to my countrymen to do? Perhaps the instinctive caution of a person who dabbles in public affairs comes in the way of my committing myself prematurely. But, if I may confess the truth, I really do not know and I do not try to find out. When I cannot act, why should I worry? I do worry to a large extent, but that is inevitable. At least, so long as I am in prison, I try to save myself from coming to grips with the problem of immediate action.

All activity seems to be far away in prison.

Excerpts from An Autobiography (1936)