Recalling the Great Non-Violent Struggle of Pashtuns against Injustice

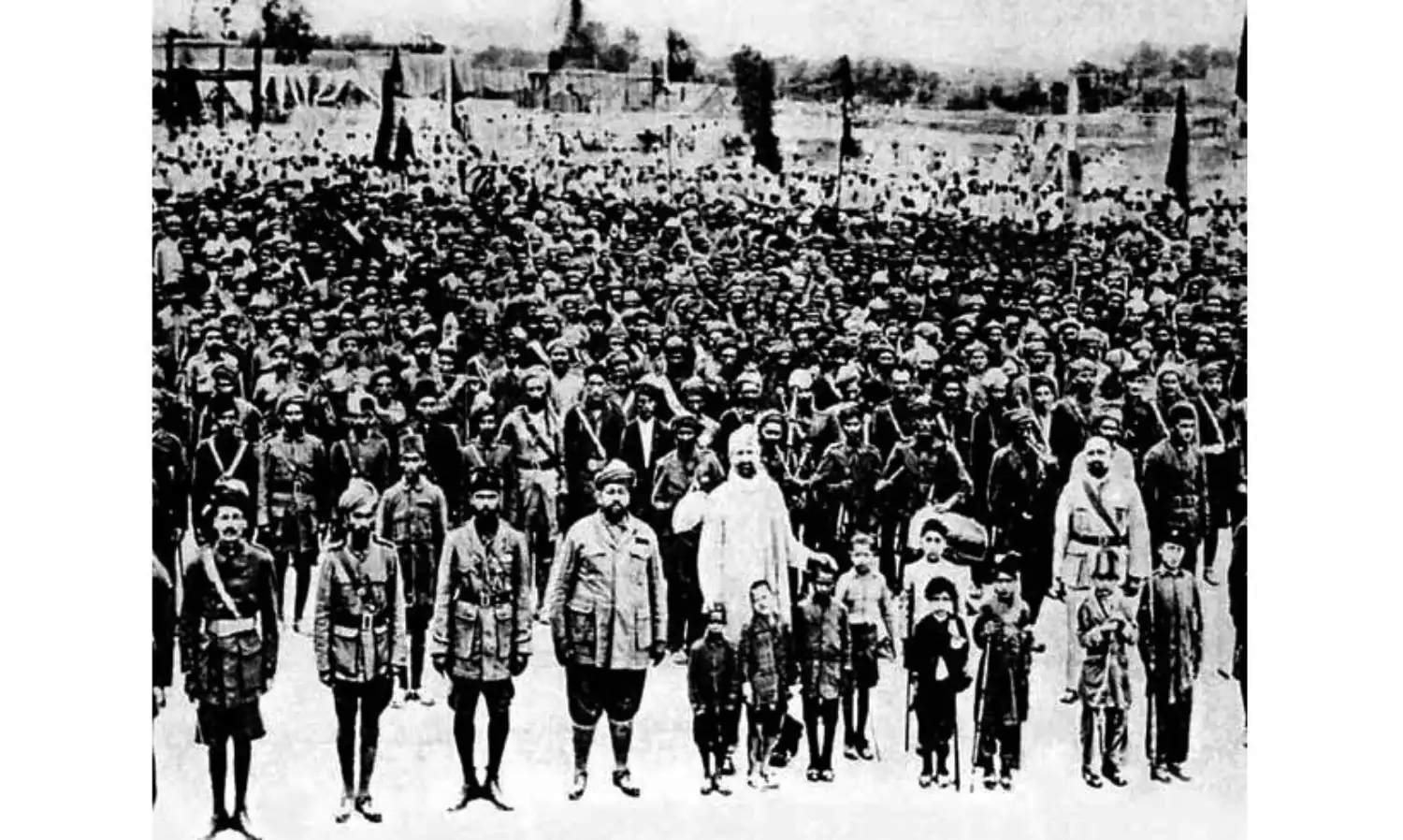

Badshah Khan and the khudai khidmatgar;

The Taliban emerged initially from the residential schools opened in Pakistan mainly for refugees from Afghanistan where highly restrictive fanatic thought was the base of education and many of the pupils had no exposure to any other worldview in their formative years. This was backed by military training and glorification of fighting and dying for a fanatic form of religion.

They were then unleashed as a heavily armed militant force for narrow political objectives in Afghanistan without heed to the very serious adverse longer-term impacts of such an action. The Taliban comprised mainly Pashtun people who live on both sides of the Durand line in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In due course a similar group with equally violent actions on the Pakistan side also emerged, although it is much smaller as it never had official support.

The Taliban are now widely regarded as one of the most violent and socially regressive forces in the world. This is largely correct, but an unintentional and unfortunate extension of this understanding is to regard the Pashtun people as a very violent people. This is wrong, and in particular it is important to recall at this juncture the time when the Pashtuns were organised for one of the most inspiring non-violent struggles which drew well-deserved extensive praise from none other than Mahatma Gandhi.

The reference here of course is to the great movement under the inspiring leadership of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (also called Badshah Khan - the King of Khans - and Frontier Gandhi) which was a non-violent freedom movement that prospered in parts of the Pashtun dominated region during 1920-1947, peaking around 1930-1935 with the involvement of nearly a hundred thousand soldiers of peace.

As is well known, these were years of freedom movement in undivided India against colonial British rule led by Mahatma Gandhi, who pioneered the biggest anti-colonial peaceful movement. In the main Pashtun area of undivided India centering around the city of Peshawar, this struggle was led by Badshah Khan, a friend and admirer of Mahatma Gandhi.

During these days Badshah Khan had successfully raised an ‘army’ of peaceful ‘soldiers’ called ‘Khudai Khidmatgar’ or servitors of God. Every khudai khidmatgar had to take this oath: ‘I am a Khudai Khidmatgar; and as God needs no service, but serving his creation is serving him, I promise to serve humanity in the name of God.

‘I promise to refrain from violence and from taking revenge. I promise to forgive those who oppress me or treat me with cruelty. I promise to refrain from taking part in feuds and quarrels and from creating enmity. I promise to treat every Pathan as my brother and friend. I promise to refrain from anti-social customs and practices. I promise to live a simple life, to practise virtue and to refrain from evil.

‘I promise to practice good manners and good behaviour and not to lead a life of idleness. I promise to devote at least two hours a day to social work.’

Describing the importance of this oath for the people of this region, Badshah Khan’s biographer Eknath Easwaran writes, “Non-violence was the heart of the oath and of the organisation. It was directed not only against the violence of British rule but against the pervasive violence of Pathan life.”

During 1930-31 came the real test of endurance of their commitment to non-violence as the colonial police and army rapidly escalated their brutal repression to check the spread of the freedom movement.

According to a report prepared by the Congress Inquiry Committee, a protest demonstration in Qissa Khawani Bazar was dispersing peacefully when “all of a sudden two or three armoured cars came at great speed from behind without giving warning of their approach and drove into the crowd. Several people were run over, of whom some were injured and a few killed on the spot. The people were not armed - [not even with] stones or bricks. The crowd behaved with great restraint, collecting the wounded and dead.”

More people collected. The troops were ordered to fire. “Several people were killed and wounded,” the report continues, “and the crowd was pushed back some distance. At about half past eleven, endeavours were made by one or two outsiders to persuade the crowd to disperse and the authorities to remove the troops and the armoured cars.

“The crowds were willing to disperse if they were allowed to remove the dead and the injured and if the armored cars and the troops were removed. The authorities, on the other hand, expressed their determination not to remove the armored cars and troops. The result was that the people did not disperse and were prepared to receive the bullets and lay down their lives. The second firing then began and, off and on, lasted for more than three hours.”

In his study of nonviolent movements, Gene Sharp includes a description of the firing in Qissa Khawani Bazaar:

“When those in front fell down wounded by the shots, those behind came forward with their breasts bared and exposed themselves to the fire, so much so that some people got as many as 21 bullet wounds in their bodies, and all the people stood their ground without getting into a panic. A young Sikh boy came and stood in front of a soldier and asked him to fire at him which the soldier unhesitatingly did, killing him. The crowd kept standing at the spot facing the soldiers and were fired at from time to time, untill there were heaps of wounded and dying lying about.”

A Lahore newspaper which represented the official view itself wrote to the effect that people came forward one after another to face the firing, and when they fell wounded they were dragged back and others came forward to be shot at. This state of things continued from 11 in the morning to 5 in the evening.

There were many more such incidents. The brave Pathans continued to pass the test of endurance and their commitment to peace and non-violence. The result was that within a few months their support increased dramatically. The Khudai Khidmatgars had started with a strength of about one thousand only, but by the end of the September there were nearly eighty thousand volunteers.

Another equally inspiring and dramatic development was when the Hindu soldiers of the Garhwal Rifles refused to fire on the peaceful Pashtun Muslim freedom fighters, even when they knew that they would get the most severe punishment for their insubordination. In fact these brave soldiers led by Chandra Singh Garhwali told their officers that they could blow them from their guns if they wanted, but they would not fire on such peaceful freedom fighters.

The peaceful resistance spread widely despite the fact that Badshah Khan and other leaders were arrested. His two sons and elder brother were also arrested.

Another inspiring aspect of the movement is that Pathan women were encouraged to participate actively in the freedom movement and many of them came forward to play an important role. Badshah Khan opposed the purdah system (veil) and emphasised the equality of women.

Several important lessons can be learnt from recalling this glorious phase of non-violent struggle. Firstly, the entire Pashtun community should not be a given a bad name because of the spread of Taliban in the area. Both in Afghanistan and Pakistan, for several decades they voted for and elected secular political parties. When a people become most violent or most peaceful depends largely on circumstances. Many Pashtuns are known to have resisted the spread of Taliban and fanatic forces even at the cost of their life.

It is when such efforts are constantly suppressed (Badshah Khan and his followers faced jails and repression even at the hands of Pakistan’s government after the end of the British rule) that the chances for people’s feelings of oppression and injustice to be pushed towards the path of fanaticism and extremism increase. This is particularly true if the government itself encourages it, as certainly happened in Pakistan for a long time.

When the Taliban was being created and prepared for a very violent role, there were hardly any efforts at the world level for checking it at the right time. Instead the big powers appear to have been supportive. Even at a later stage when the dangers of unleashing a very fanatic armed force capable of capturing state power were becoming clearer, there were not much efforts to check this.

An important question is: what was the official response to the forces of peace?

It is well known that the colonial rulers were cruel in suppressing it. But after independence and partition, under the new Pakistani government too Badshah Khan had to spend most of his time in jail and/or under serious restrictions. So many cases were foisted on him and he faced so many difficulties and oppression that he just could not get the opportunities he needed to spread his message of peace among more people.

The international community also neglected this important force of peace and its leader. On the other hand those who worked in a framework of violence and fanaticism continued to get a lot of support and funds, and this increased greatly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

The chances of building a peaceful resistance never got a chance. As this region became more and more an area of big-power rivalry, the entire effort by big powers was to get the support of one violent group or the other to sort out immediate issues, and in the process opium cultivation, its processing into heroin and smuggling were all boosted, with more and more people getting addicted and also dependent on it for economic support.

Hence the region was pushed more and more towards becoming a region of guns and opium, a far cry from the world of peace, cooperation and philanthropy which Badshah Khan had tried to create for his people.

Can his vision be revived again today for this deeply troubled region? This is the question that needs to be asked by all peace-loving people.

Bharat Dogra is a journalist and author who has written on peace, justice and ecology for nearly five decades