WhatsApp Alleges Indian Political Parties are Misusing the Service for Election Gains

The BJP plans to create three WhatsApp groups for each of India’s 927,533 polling booths;

India’s political parties are misusing the social messaging service WhatsApp, said a senior executive on Wednesday. Carl Woog, head of communications for WhatsApp, told reporters there’s mounting concern that party workers in India may misuse the app to spread false information and sway voters ahead of the 2019 general election.

“We have seen a number of parties attempt to use WhatsApp in ways that it was not intended for, and our firm message to them is that using it in that way will result in bans from our service,” Woog said. The company did not name any political parties or give details of the alleged misuse, but cautioned against the use of automated tools for mass messaging.

India’s next Parliament will represent a society that is far more technology driven and influenced than ever before. Five years ago only one in five Indians owned a smartphone. Now that number has almost doubled, to 39 percent.

WhatsApp is the most popular social media service here by far, with over 200 million people estimated to be using the app. Its popularity prompted the head of the governing Bharatiya Janata Party’s IT cell, Amit Malviya, to dub the 2019 elections the “WhatsApp Elections”.

The popularity of social media apps, especially among young voters, has led to a situation where political parties are stepping up efforts to increase their digital presence, while also criticising the spread of rumours and “misinformation” through social media.

Sources say that the BJP has drawn up plans to create three WhatsApp groups for each of India’s 927,533 polling booths.

The Congress has its own social media strategy, also heavily reliant on WhatsApp groups and forwards, and regional parties are not far behind.

This writer witnessed the power of WhatsApp groups in informing electoral strategy whilst covering the Gujarat assembly elections in 2017. As our team of reporters entered Vadgam, the constituency Jignesh Mevani contested from and won, we were told that WhatsApp messages had been doing the rounds asking people not to let Mevani enter their villages.

“He’s said things such as ‘Modi ho ya guy, kar do usko bye bye’ - Modi or a cow, bid them goodbye now - and that if he had two sisters he would marry one of them off to a Muslim. These type of comments haven’t gone down well with the Hindu community at large,” a local resident Mukesh told us at the time.

These WhatsApp messages were circulated in groups consisting solely of Hindu voters in the area.

The practice of classifying voters on the basis of their religion - but also their caste, economic status, age and location - is reportedly a key component of the political social media strategy.

Shivam Shankar Singh, who for two years worked in data analytics for the BJP, told TIME magazine that ahead of the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections, WhatsApp groups were created along caste lines.

“That allowed the BJP to send a specific message to a specific caste group. It’s basically used to reinforce things... So if you have certain anti-Muslim tendencies, then the propaganda will be directed to telling you how bad Muslims are.”

“Everyone is playing the game,” said a political party source on condition of anonymity. “The BJP is far ahead, because they were first to focus on a social media strategy, but also because they have more resources than anyone else.”

The problem isn’t so much the WhatsApp groups being created by political parties - and joined by voters - but rather the nature of the content being circulated in them, the party source said.

“It’s the kind of stuff you’ll never see on the verified social media handles of any political party. For instance, groups created by BJP workers will often have a lot of forwards about claims like Muslims overtaking Hindus in India, or supposed proof that a temple existed below the Babri Mosque.”

Last month, on Facebook, Twitter and in WhatsApp groups, an image of an old man who had seemingly committed suicide by hanging was accompanied by a message claiming that one more priest from the Ram Janki temple in Raebareli had been murdered by “jihadis”.

The image was circulated through social media, particularly in pro-BJP WhatsApp groups, with an emphasis on the word jihadis, used as shorthand for Muslims.

The information accompanying the image was debunked by online fact checkers, most prominent among them the website AltNews. However, the false connection to “jihadis” had already served its purpose, and as each WhatsApp group comprises a closed list of 256 people, the reach of fact checking initiatives remains limited.

The example illustrates how easy it is to spread misinformation on closed services like WhatsApp, without any checks or balances. “There is the risk of misinformation leading to violence,” the party source admitted.

Parties, the government and big media have remained silent about the vacuum created by the erosion of a free press, which is evidently being filled by users of social media services, preferring instead to blame the app itself.

In 2018 the Indian government pulled up WhatsApp over a spate of lynchings across the country, fuelled by rumours that were spread using the messaging service. The ministry of information technology declared that a large number of “irresponsible and explosive messages filled with rumours and provocation” were being circulated on WhatsApp.

At least 30 people were lynched in different parts of the country on various pretexts, in what came to be known as the “WhatsApp killings”. Nothing was said about the people or organisations at the source of these rumours, who were able in an infamous case to assemble a thousands-strong mob on 20 minutes’ notice.

WhatsApp responded by reducing the number of contacts or groups a user could forward a message to, from 100 down to five in India, and to 20 globally.

“It’s a step,” said the party source, “but you’re battling sheer manpower. Besides, you can forward to five people 20 times and still get to a hundred.”

With polls approaching, political parties are finding ways to circumvent the restrictions placed by WhatsApp, after joining with the government to pressure the company to impose those limitations in the first place.

Woog, speaking to reporters, said that the company was engaging with political parties to explain that the app was not a “broadcast platform”.

“We are trying to be very clear going into the election that there is abuse on WhatsApp. We are working very hard to identify it and prevent it as soon as possible,” he said.

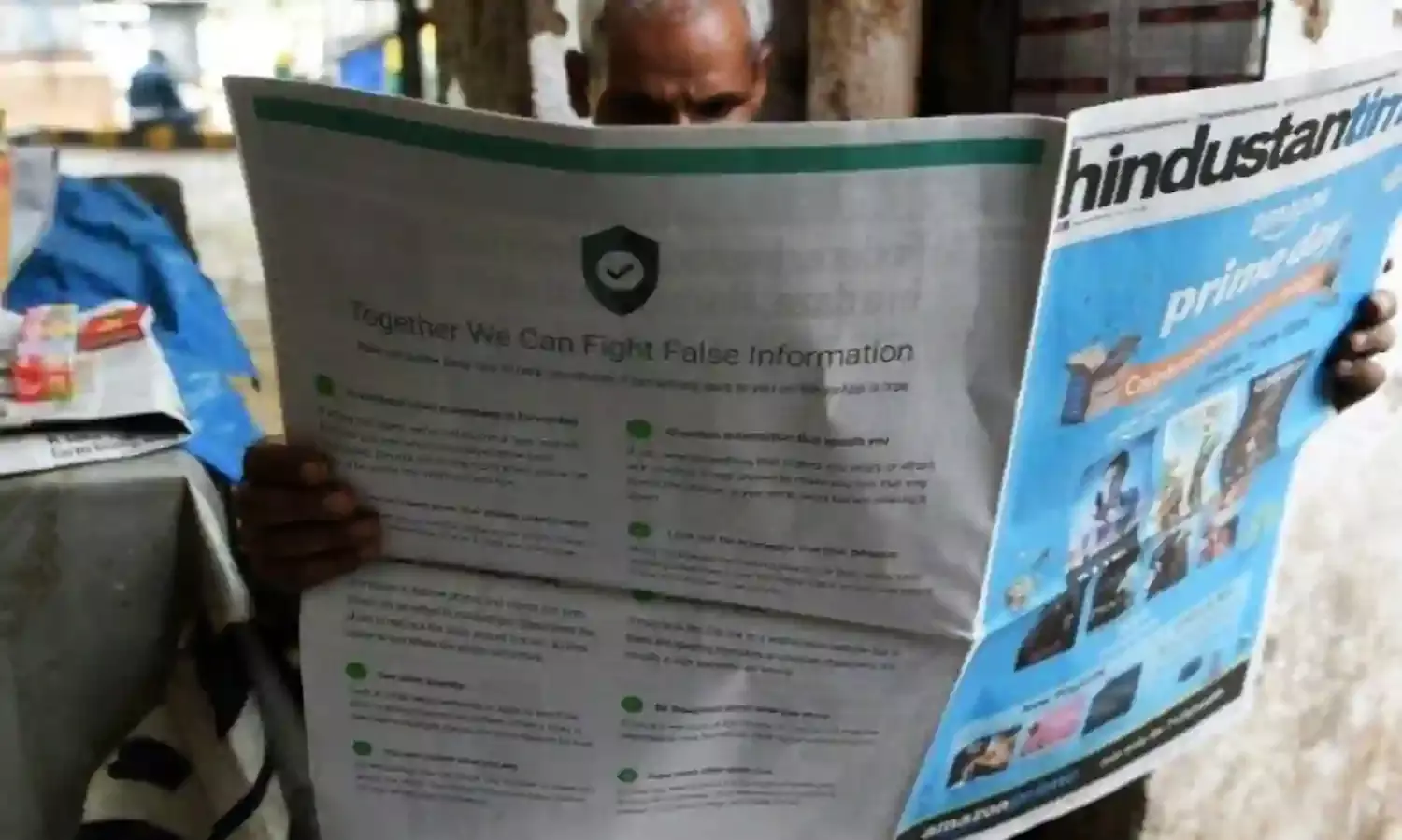

(Cover Photo: WhatsApp took out full-page advertisements in Indian newspapers offering "easy tips" to identify fact from fiction.)