At the Hyderabad Zoo with friends recently one was shocked to hear them introducing mammals to their kids; each reference was from characters in animated Disney films. Films made in another continent, speaking a language different from that which the kids spoke at home and presumably not made with Indian kids as the primary audience.

There was neither a single mention of species that find place in our ever alive mythologies nor of those mentioned in their school text books or story books. No mammal, except the lion, was identified as being part of the state. Eavesdropping on conversations of other families during the trip, and speaking to others after the trip,confirmed the fears. This was possibly how a majority of our urban house-holds perceive forests and wildlife.

Sheer disconnect of the urban population from a part of its cultural heritage; the wild life that we share the country with. Our disconnect from forests has meant that the forests and wildlife are not part of our lives, conversations and ethos.

Vadodara, for example, a city that gets its name from banyan (vad) and is home to approximately 150 odd crocodiles along the 25 km stretch of river that runs through it, is not associated with either. That the Gendi Gate, a landmark at the heart of the city, was named thus on account of rhino fights held at the venue, for the Prince of Wales more than a century ago, was not a fact known to many even in the city!

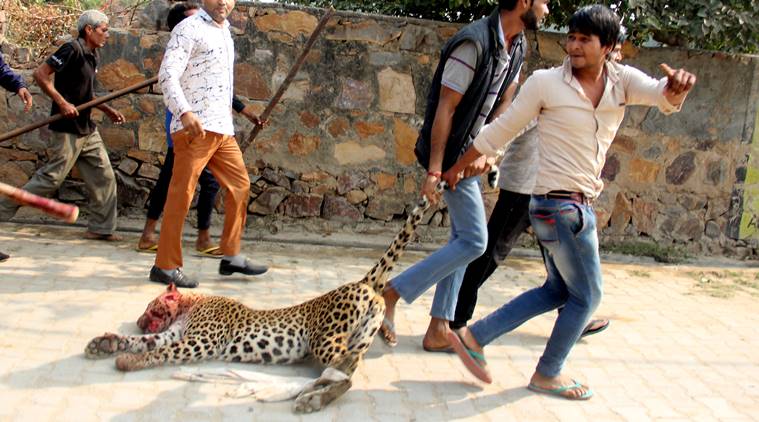

Forests and wildlife have acquired an almost negative connotation. They are to be feared, to be stayed away from and its denizens akin to thugs of the British era. Little wonder then than we do not allow few of those who are spotted in our urban areas to continue with their lives.

The scenario appears all the more stark when we consider that we as a nation are

- Leaders in wildlife research in the region; we also train people from neighbouring countries:

- One of the most tolerant nations in the world if we go by the number and diversity of animals.

This increasing disconnect of the urban population from forests and wildlife raises some uncomfortable questions.

Is it due to our education system which from our initial years gives us a distorted picture of animals? We have school text-books with sentences like ‘cows give milk’ or ‘wild animals stay in national parks and wildlife sanctuaries’. Have they ended up conveying that wildlife and forests are far off? Which cow voluntarily gives milk or which wild animals are aware to boundaries of our national parks and sanctuaries is a discussion for another time.

On the other hand we also boast of a vast body of work on environment education. From actions by the BNHS almost a century ago to the backing by the highest Court in the country. Have these efforts failed to deliver?

Are we just not bothered? When we go for safaris in tiger reserves we are not bothered about the species other than the tiger and we do not think twice about troubling the animals in the zoo. This author recalls being told by a tourist that till the tiger comes around the canter everyone should play music! Some months ago police in Hyderabad filed a case against a young man for getting into the tortoise enclosure and standing on the poor creature. He clicked pictures and even had the audacity to put them up on the social media. This could hold true for environment as a whole if we are to look at the images of trash generated at the Cold Play concert after taking pledges to the contrary.

We appear to have become tuned to be scared of the unknown rather than be thrilled to get the opportunity for fresh experiences. On top of it we seem to possess an endless urge to control and manage. As a consequence we are scared of walking in a forest though it may bear far less risk than walking in our city and we are comfortable in situations where we can control and manage the forests and wildlife. Forests and wildlife are also fine on our calendars, t-shirts and computer screens where they are sterile and dead.

Have we miserably failed to preach beyond the proverbial choir? In its rush for conferences and publications is the wildlife conservation community left with no time for the community beyond its small circle? To add to it many of the publications which come up from the circle are meant to be understood and read by a few.

These and other questions on similar lines are pertinent as we rush from a primarily rural to an urban country. Deliberations on some of these may help us understand if and how these urban areas will survive, sustain and flourish in the long run.