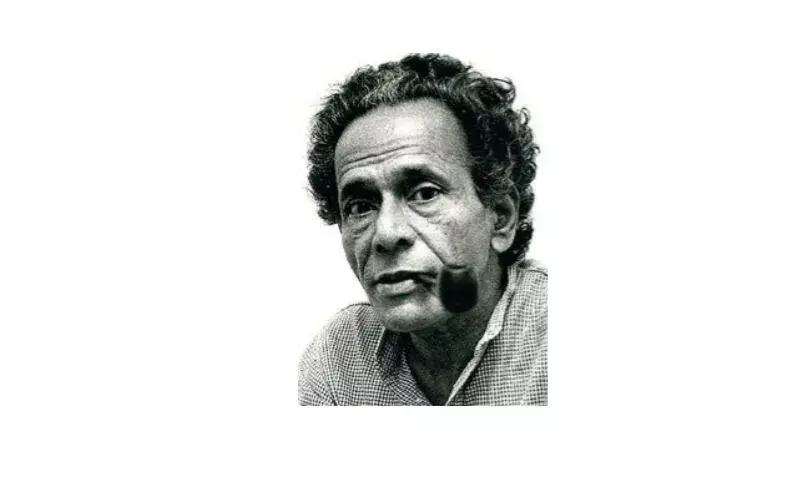

Theatre personalities from Mumbai, Kolkata and Delhi came together to celebrate the centenary of legendary Habib Tanvir under banner name ‘Dekh Rahe Hai Nayan; over August 30, 31 and September 1. The celebrations included master classes, panel discussions by theatre veterans, a book launch, film screenings, music performances and a dastangoi tribute to Habib Tanvir and his contribution to the history of theatre not only in India but across the world.

The programmes were curated by the theatre stalwart M. K. Raina and Tausif Rahman, in consultation with noted theatre critic and author Anjum Katyal of Kolkata.

Veterans such as Naseeruddin Shah, Ratna Pathak Shah, Raghuvir Yadav, Sudheer Mishra, and theatre giants from Bengali theatre came together to pay their respects to Habib Tanvir. Each of these theatre veterans spoke about how their association with Tanvir had changed their way of thinking about theatre and about life forever.

Tanvir, the legend of contemporary Indian theatre, was also a writer, poet, actor, organiser of progressive writers and people’s theatre. He passed away on June 8, 2009 at Bhopal. Tanvir, whose plays make him a true citizen of the world, will be remembered for his abiding commitment to the values of secularism and progressive ideas.

His ideology was shaped in the crucible of the left wing cultural movement particularly IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association) and (Progressive Writers’ Association).

This writer had met him only once backstage at a Mumbai theatre, after his group had staged Charandas Chor many years ago as part of a theatre festival. I could see that I was meeting one of the most grounded personalities in the country. He introduced me to his Bengali wife and their pretty daughter.

In the midst of urban angst and modern plays with and without props, Charandas Chor was a delight, with its fluctuations between satire and the politics of being, embellished with simple narrative and wonderful acting. The idea took a little time to seep in, conditioned as I was, to the completely different oeuvre of Bahurupi, Badal Sircar and Utpal Dutt. But when the reflection began, the memory remained archived in my memory.

Tanvir’s approach to folk culture distinguishes itself sharply from other contemporary theatres and theatre directors. His approach and idea about the folk in particular and his cultural consciousness in general, evolved within the left wing cultural movement particularly IPTA.

Tanvir’s theatre drew on folk elements in the drama and on the other, there are elements of the revivalist and archaic kind of traditional theatre. Tanvir’s theatre offers an incisive blend of tradition and modernity, folk creativity and skill along with the medium critical consciousness.

‘Agra Bazar’(1954), was based on the times of the 18-th-century Urdu poet, Nazir Akbarabadi, an older poet in the generation of Mirza Ghalib. He used students of Jamia Millia Islamia, local residents and folk artists from Okhla village and created an ambience never seen before in Indian theatre.

The play was not staged in a restricted space, but in a bazaar, a marketplace. Set in the early nineteenth century amid the bustle of a colourful street market in the iconic North Indian city, the play is woven together by the wonderfully human voice of the poet Nazir, which explores some of important cultural and socio-economic issues of the period, such as the declining influence of the Urdu language and the growing power of English in colonial India.

In 1958, he formed Naya Theatre with his wife. Tanvir’s abiding contribution to contemporary culture is his remarkable incorporation of traditions of folk and tribal theatre, music and language into his modern formal craft.

The power of his plays delighted and moved audiences cutting across all class boundaries from the man on the street to the powerful elite. The many awards and accolades – the Sangeet Natak Academy Award (1969), the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship (1979), Padmashri (1983) and Padma Bhushan (2002) among many others sat very lightly on his slender shoulders.

A story goes that he had once asked Naseeruddin Shah how much he should charge for a role in a film offered by a Mumbai producer. Naseeruddin asked him to quote Rs. 10 lakhs but he asked for just Rs. 3 lakhs! That was Habib Tanvir for you.

Tanvir was perhaps the first theatre director to incorporate the sense of folk material in the Indian theatre and among them, songs were the first of its kind to be used in his plays. Apart from finding these songs attractive, it had a strong anthropological interest and Habib went out of his way to learn and experience its musical insights.

The interest for the music can be gathered from his childhood days and his experience in IPTA for exposing him to the wide variety of folk music in India.

Chhattisgarh region has rich forms of folk elements and a wide range of folk tunes. Habib Tanvir remembered songs that were sung in the fields, at harvest time, in the temples, during the rituals and those authentic songs, death songs, marriage songs that were a part of regular life there.

But instead of its vastness, Tanvir could manage to reflect a little of it on the rustic stage. He slowly realised that the traditional form was disappearing with the influx of modernity taking the folk elements away with it. He took upon himself the agenda of saving it from extinction. He decided to incorporate these into his production.

Tanvir taught his troupe these folk songs, locating them at the workshops, from older artists. Besides collecting traditional songs, Habib very imaginatively blended the folk tunes with the existing melodies or interwove traditional words with newly written verses.

In ‘Agra Bazaar’, songs are used to make philosophical comments on the action as well in the narrative form as mentioned in the scene of the fakir’s songs and the vendors’ songs. Tanvir was less concerned about using elements of song and music as an extrinsic to the essential dramatic unfolding of the play in the form of fillers or interludes.

He used music and songs as an intrinsic feature linked directly to other aspects of the structure of a play. He managed plays with a mammoth cast, such as ’Charandas Chor’, which included an orchestra of 72 people on stage and ’Agra Bazaar’, with 52 people.

‘Charandas Chor’ (1975), Tanvir’s most famous work, based on a story by Vijaydan Detha is about a typical folk hero who robs the rich much in the style of Robin Hood and evades the law until he comes up against one wall he cannot scale—his own commitment to the truth.

Tanvir’s theatre was not fixed to any one form as a whole. His works reaped the skills and energies rooted in folk performance and made them relevant to secular and democratic perspectives.

This made his performances on stage or anywhere, challenging, thought-provoking and entertaining. The play is often described to be a play of paradoxes which shows that Charandas, a thief by his own admission, is more “honest” and truthful than wealthier, ordinary and elitist people who are greedy, exploitative and corrupt. This includes his own guru who made him take five vows and Charandas did not break one even once.

During the five decades of his stint in theatre, Tanvir gave memorable productions like ‘Agra Bazar’ [1954], ‘Mitti ki Gari’ [1958], ‘Gaon ka Naam Sasural Mor Naam Damaad’ [1973], ‘Charandas Chor’ [1975], ‘Jis Lahore Ni Dekhya’ [1990], and ‘Rajrakt’ [2006], of which many are renowned as classics of the contemporary Indian stage.

Though initially, he directed his folk plays with Hindi dialogue, he later changed them to the original Chhattisgarhi dialects and though they were a bit tough to follow, this did not affect their popularity among the audience.

He also did cameo and character roles in Hindi films. One memorable role was in Sudhir Mishra’s ‘Yeh Woh Manzil To Nahin’ which was a politico-historical film. Others are ‘Prahaar’ directed by Nana Patekar, ‘Charandas Chor’ directed by Shyam Benegal and ‘Gandhi’ directed by Richard Attenborough.

Tanvir once said, “Unless we can go back to our own traditions and bring a world of consciousness to bear upon the knowledge of our own tradition, we cannot evolve the new kind of vehicle of expression which is necessary for a technical age, where the new demands are made.”