THE LEGACY OF MANMOHAN SINGH

The late PM Could Not Put Politics Back Into Economics Where It Belongs;

Manmohan Singh straddled the Indian economic and political scene for several decades. Those who have gathered to praise or to bury him must assess his legacy against the transformations that rocked the country during those years. His career touched every high spot in government that an economist could dream of. There were stints as Secretary and Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, Chief Economic Advisor and Secretary to the Government of India followed by elevation to the role of Reserve Bank Governor.

Like his colleagues of the era, he began as a die-hard socialist, schooled in dirigiste policies-licensing, public sector control of the “commanding heights” of the economy and a fixed exchange rate. This was the avatar that I first saw when, as Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, he approved the size of State development plans in meetings held with Chief Ministers.

Soon after, his career took a completely different turn to make him, in the eyes of his countrymen, the architect of the economic liberalization, which was ushered in by the 1991 Central budget. We cannot apportion blame or praise for this action, without understanding his role in the exercise and the background and consequences of the policy itself.

The decision to liberalise was not taken by Manmohan Singh, nor were the first radical measures heralded by the 1991 budget speech prepared by him. A coterie of insiders of the Finance, Industries and Commerce ministries had broken the bad news about the dire state of the country’s balance of payments, debt and budgetary situations to the V P Singh cabinet on 1st July 1990. Foreign exchange reserves were barely enough to cover a week’s liabilities. The only way out was an IMF loan, which would come with strings attached.

As the country went to the polls after the collapse of the V. P. Singh coalition, a first slew of reforms to placate the IMF was being designed by a four member committee (of which I was a member), chaired by A. N. Verma, Secretary (Industrial Development), who later became the principal secretary to incoming Prime Minister Narasimha Rao.

“Reform by stealth” seemed the easiest way to avoid criticism and opposition to the essential radical changes, which were presented to the new PM. The blueprint of liberalization was thus a fait accompli when Manmohan Singh was inducted as Finance Minister. Remembering his socialist credentials, however, a senior civil servant who was actively involved in resolving the crisis even expressed the fear that he might not be the right person for the job. This was a gross underestimation of Manmohan Singh’s ability to learn and to adapt. In less than three months, after the landmark budget speech of 1991 laid out the contours of reform, the IMF loan was approved and the country saved from chaos of the kind experienced recently by Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Detractors of liberalisation are wrong to assume that the Finance Minister was only dancing to the tune of the IMF. We are today so totally attuned to its benefits that we have forgotten the sclerotic controls that had strangled entrepreneurship and economic activity before 1991.

The policies of that year dismantled the industrial licensing regime, introduced a floating rupee exchange rate, removed trade barriers, reduced duties to WTO levels and transferred the management of external borrowings from government to the RBI and equity and bond issues to the newly created regulatory body, SEBI.

The Narasimham Committee’s recommendations on financial sector reforms became the basis for setting up private banks and insurance companies and empowering them to recruit employees and set interest rates. Prices of petroleum products were also proposed to be linked to international movements.

Manmohan Singh did not invent liberalization, but, with the backing of Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, he became a willing front for launching the first round of reforms that had already been planned and prepared by others.

Liberalisation saved us from chaos and swept India into the global economy. The Finance Minister and his colleagues must, however, be faulted for letting it splutter to a halt, when the IMF pressure was lifted as reserves improved and the loan facility withdrawn. Retreating before the first signs of opposition and protest, they let the momentum of reform peter out over the next two years.

Unfinished tasks which are still pending include the framing of labour laws that are fair to both employers and workers and the rationalization of procedures for setting up and running businesses. The farm sector is untouched, since cultivators still have little access to inputs, credit, markets, crop insurance or fair prices.

We have the largest proportion of young people of any country, but we do not yet have a vision for providing them education, health or social security through the combined efforts of the public and private sectors, as many European countries do. Partly-done liberalization measures have, on the other hand, handed the economy over to crony capitalists and created acute income inequalities, high levels of unemployment, malnutrition and poverty with poor prospects of growth.

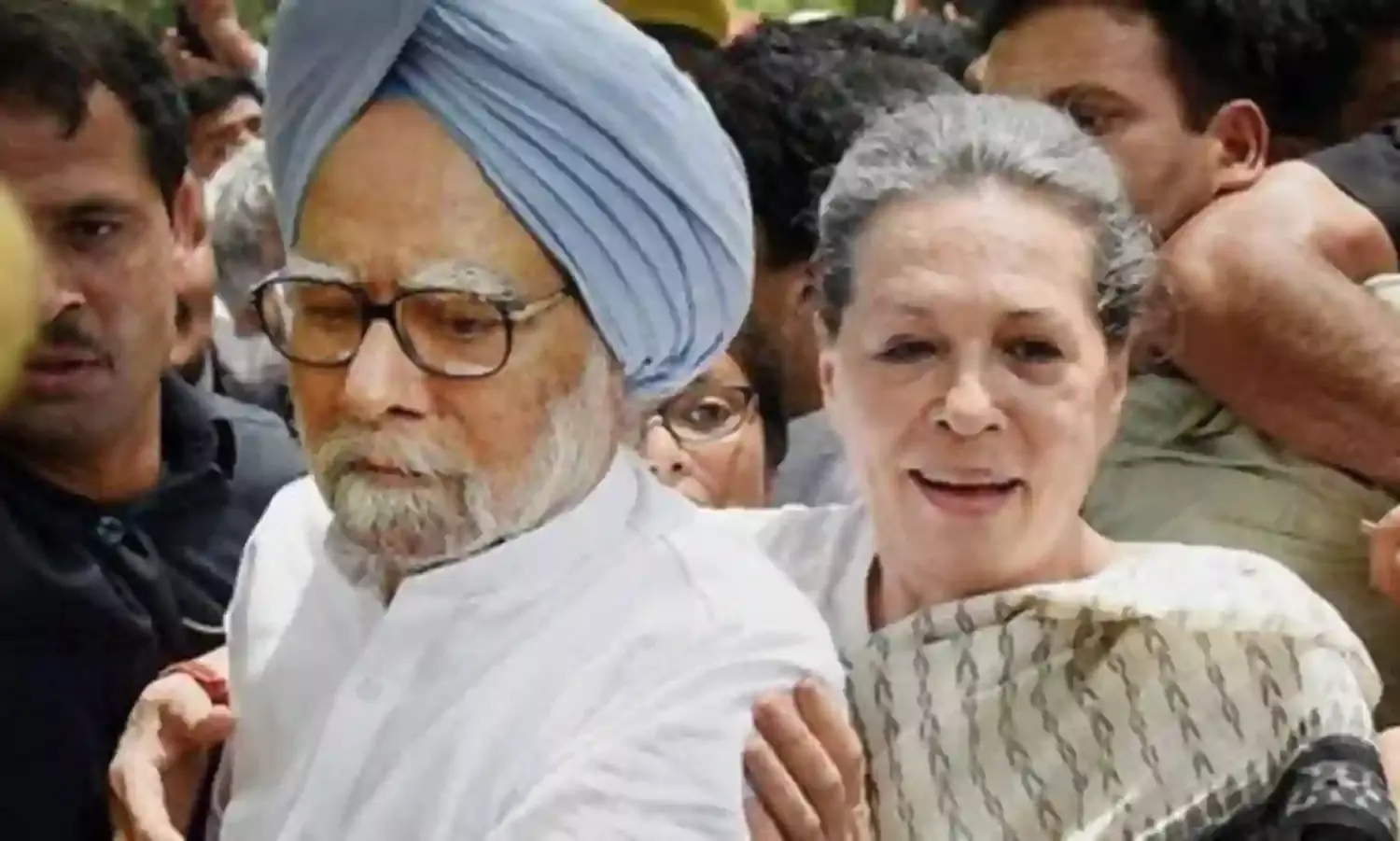

With the shift to political management on becoming Finance Minister, Manmohan Singh honed his oratorical skills through learned interventions in Parliamentary debates. He was rewarded with membership of the Rajya Sabha, after the Congress government was replaced by the NDA. His final chance to leave a mark on the country’s development came when greatness was thrust upon him, when Congress President, Sonia Gandhi, placed him at the head of the UPA coalition after winning the 2004 election.

The selection of Manmohan Singh was hardly accidental. Other senior leaders, who could claim the position (Pranab Mukherjee, Arjun Singh or even Chidambaram) had at one time or another defected from the Congress for short periods of time. As a person with no political backing, Manmohan Singh was the only one who could be relied upon to step aside when needed to install the member of the Nehru-Gandhi family being groomed for the job.

His appointment was noteworthy, because he was a “nominated” prime minister, who would spend the entire decade of prime-ministership as a member of the Rajya Sabha, at the very limit of democratic functioning that you can get under a cabinet system of government. There is no legal bar to the government being led by a Parliamentarian of either House. The implicit assumption is, however, that the situation will be “regularised” as quickly as possible by getting her/him elected to the House of the People.

What Manmohan Singh did is tantamount to a British PM, being drawn from the House of Lords, which is unthinkable in this day and age. Could we contemplate Jawaharlal Nehru, for example, running his prime ministership as a member of the Rajya Sabha? Manmohan Singh never tested his position and political legitimacy by turning to the voters of any constituency to endorse him and his policies.

Yet, opposition leaders, the media and observers of the political scene, national and international, chose to ignore this patent democratic anomaly in the largest democracy of the world. It is rarely alluded to perhaps, because politicians of all persuasions and parties would like to follow the Manmohan Singh example and rise to prime-ministership without facing the arduous test of the popular vote!

The elevation of Manmohan Singh as Prime Minister was also an experiment in separating political management and governance, leaving the former to the party and the latter in the safe hands of an economic expert. An apolitical person as prime minister was particularly anomalous for the monolithic Congress, in which power is generally concentrated in the hands of the prime minister.

During the Singh decade, however, political leadership remained with the Party leader, who took decisions in conclaves in which the PM took a back seat. Manmohan Singh set himself no political goals; his role was formal, ceremonial and consensual. He was content to be a spokesman, mouthing public justifications for party decisions and assuming the party mantle when directed by the leader.

Within Parliament, he performed legislative and debating functions, as he had done earlier as Finance Minister and member of the Rajya Sabha. But, he took no interest in formulating tactics to embarrass or outwit the opposition. We saw him occasionally looking uncomfortable and out of his depth at political rallies, although remaining a member of the Working Committee.

Unlike the general run of economists who are immersed in abstract concepts and statistics, Manmohan Singh was compassionate and open to populist arguments and explanations. But, deprived of the obligation to win elections, he never acquired the skills that come from campaigning in streets and houses, holding public meetings and mingling with the common herd. Although eloquent and effective in Parliament and on podia, he could not communicate politically with ordinary people. His Red Fort speeches on Independence Day improved over time but were never memorable. He was respected by the public, yet did not arouse the affection commanded by popular leaders.

Manmohan Singh must then be judged not by the political yardstick but by the progress in achieving developmental goals and the performance of the country’s economy-the areas in which the Congress party sought his leadership and in which he hoped to make a difference, while accepting the prime-ministership.

He teased out a consensus with techniques learned at the Planning Commission, using Cabinet Committees, headed by senior colleagues to formulate answers to thorny issues and disperse prime-ministerial powers among rivals like Pranab Mukherjee, who was later placated by the award of the Presidency. He also scrupulously respected and deferred to consultative procedures and Parliamentary institutions, a practice that has been rudely discarded by the Modi government.

From day one, Manmohan Singh set his sights as PM on putting the country on a double digit growth path. And there was general rejoicing when it happened at last in 2010. Only to quickly slump to the familiar level-close to the “Hindu” rate of growth of 3.5%.

The excuse that this was due to the worldwide recession that followed the 2008 financial crisis is not credible. As an inward-looking economy, with a large population in the working age bracket with capacity for hard work and a huge appetite for infrastructure and consumer goods, India was the ideal environment for a successful stimulus program. It could have drawn on idle productive capacity around the world to upgrade infrastructure-build roads, schools, railway lines, hospitals, metros and urban facilities-, unleash the potential and skills of its people, create employment and stimulate growth.

Financial resources could have been raised for the purpose through spectrum auctions (if not to levels overestimated by the CAG) without raising taxes, increasing the debt burden or selling the crown jewels (public undertakings). Unfortunately, the telecom and surface transport departments which had to be mobilized were run by ministers belonging to a coalition partner, who were slow to cooperate.

The only solution was political. The DMK supremo, Karunanidhi had to be invited to join the national effort to transform the economy. In the absence of a communicator of the caliber of G K Moopanar to convey the message, the party and the prime minister failed to achieve the impossible.

A part of the blame could be laid at the doors of coalition politics. Never, during the Singh decade, did he assume his rightful role as economic leader within the UPA, nor even among the Congress ministers of his cabinet. In retrospect it appears that many of these excuses and constraints were exaggerated. It is widely known that the PM had got his way by threatening to step down when the Left parties were baying at his heels for bowing to the nuclear deal. On that occasion, Sonia Gandhi had rallied around the PM and risked the fall of the government.

It seems today that he had chosen the wrong issue to take a stand. The country might have been better off if he had perceived his primary mission to be its modernisation and rejuvenation so that it could realize its potential. And sought to achieve this by raising resources through spectrum auctions for investment in the critical sectors that were crying out for public capital.

At a more mundane level, however, Manmohan Singh did a great deal to revamp schemes in many sectors. We who worked in the Planning Commission in that period were involved in pushing through innovations like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Program, the Health and Urban Development Missions and the Right to Information Act, which have substantially improved the lives of citizens. Even the hostile government that replaced the UPA in 2014 has not dared to abandon these programs.

But, Manmohan Singh never functioned as primus inter pares among the Congress ministers of his cabinet. It is not clear if he had been invested with authority over all of them or whether he chose not to exercise it. Without it, he enjoyed minimal influence in economic policymaking. His vaunted abilities in finance and his claim to have liberalized the economy in the nineteen nineties had earned him the prime ministerial chair, but these abilities remain unutilized throughout the decade as prime minister.

No wonder, within the government, there was poor understanding about the fallout of the recession in India and adverse global events were tackled in an uncoordinated and lacklustre fashion.

When Singh became prime minister, many hoped that an honest prime minister could by himself introduce the right policies and provide good governance. That myth has now been shattered. Corruption is a luxury that we cannot afford. It is useless for Congress leaders and some others to applaud Manmohan Singh for being “personally honest” whatever that means. No one emulated him, some even mocked him.

For the country to develop, the muck heap of politics must itself be cleansed in the public gaze by patriots who put principles before position and the country’s welfare ahead of party considerations. The Aam Aadmi Party has repeatedly shown that personal and party finances can be transparent and clean. Every rupee of public spending must filter through to our hungry people.

The biggest lesson from Manmohan Singh’s shortcomings as Prime Minister is that political power must not be divorced from political responsibility, as the Congress tried to do with a prime minister distanced from the electorate. We cannot afford another prime minister from the Rajya Sabha, who has not sought popular support or has already been rejected by voters. Even the newest kids on the block, the novices from the Aam Aadmi party, have shown their mettle by vigorous campaigning,

Adam Smith, the father of economics, had a good reason for referring to it as political economy. The late PM could not put the politics back into economic policy, which is where it belongs.

Renuka Viswanathan retired from the Indian Administrative Service. The views expressed here are the writer’s own.