Discriminated In Life, And in Death

Kashmir’s transgender community

Around 17 years ago, when Tahir Jan, a transgender person, left her parental home in Baramulla district, she only carried some clothes and a few hundred rupees. She said she had no idea then if she would come back home or go live in Srinagar.

In her village in Sopore, she recalls, she had to behave in a certain way. Her family told her how to dress and had put restrictions on her movements. Tahir, now 40, who identifies as a woman, wanted to experience life away from home in Srinagar, without having to bother what her family would think of her.

Once in Srinagar, she never thought of going back and immediately started work as a wedding singer. This she said would not have been possible while living with her family. Later, Tahir moved to becoming a matchmaker, and today, she continues to earn her livelihood from both.

“I had not come to do matchmaking in Srinagar but had come to sing at a wedding without my family knowing about it,” recalls Tahir, who lived with a local family in Srinagar for two years before moving out to live on her own.

In Srinagar, she said she received the support of the transgender community. She was quickly taken in and made a part of the community. Tahir said she started rebuilding her life from scratch. Once she started living and moving around with her community members, she felt her home was with them.

Tahir has not received any monetary help from her family in the past 17 years. As her parents are alive, there has been no mention of, or discussion on, giving Tahir her share from the property.

She may never get her share in the property of her parents, but she knows she has a right over one thing owned by her family, the family graveyard.

“When I am old and feel it is my time to leave the world, I will go back to my native place in Sopore. I know my family will take care of me as they adore me. My graveyard is there and I will be buried there near my forefathers,” said Tahir.

Like other transgender people, Tahir has never thought of buying land for the graveyard in Srinagar because she knows that is one thing that her family will have to give her when she dies.

As per the local tradition in Kashmir, parental property in most cases gets divided among siblings after the passing away of one or both parents. It is rare that parents divide the property among children when alive. Children usually inherit the graveyards too, just like property.

One thing that still connects Tahir and many others like her to their families living in their native villages is the family graveyard, which they will share one day.

Originally from Lalbab Sahib, Arampora, in Baramulla district’s Sopore, when Tahir arrived in Srinagar as a young 20-year-old in 2005, she lived in a rented accommodation in the Alochi Bagh area of Srinagar till 2011.

Proud of her achievements over the years, Tahir, said she finally bought a small two-storey house for Rs 10 lakh in Habba Kadal, Srinagar, five years ago by taking loans. “I am thankful to God for this house that I was able to buy from my hard work,” Tahir said.

Dressed in a striped ‘pheran’ and a chequered black and white scarf, Tahir’s single room first storey home is both a kitchen, a drawing room and a dressing room.

Tahir, who dropped out in school in Class V, fondly remembers her days in her native village.

“My family didn’t like that I was doing matchmaking and singing and dancing at weddings. Till 2008, my mother would tell me to leave all this and do something else. Now this is all I can do,” said Tahir, who comes from a well educated family in Arampora.

Tahir Jan is not the only transgender who has not got their share from their ancestral property. She said she has never talked about her property rights with her parents or siblings.

“Why should I ask for my share in the property and sour the relationship with my siblings? I don’t think my family will ever give me my share in the property when they haven’t talked about it for so many years,” she said, adding as an afterthought, “even if they give me the share, at the end it goes back to them so why ask for it.”

Living alone in her small two storied-house, Tahir talks about her mother and how she pampers her when she visits home occasionally. She lovingly remembers each detail and brightens up.

Though she said her family loves her, she is reluctant to get photographed because she said her nephews and nieces do not like it and one has to also think about them.

“After all, I am a transgender and my family would have to hear this all their life. They have to live with it. Nobody is going to forget that my parents gave birth to me, a transgender,” she said.

Most of the transgenders who come from other districts of Kashmir come to Srinagar in search of a livelihood. Many are school dropouts and cannot get an office job. The city soon becomes their permanent home.

While some transgender people earn enough to buy a small property, many others live on rent, or with their community members in the old city area of Srinagar.

Though they buy houses here, for most of them buying a piece of burial land in a graveyard is never on the agenda. The graveyard forms a part of the property of any Kashmiri. It is either inherited or has to be purchased unlike in the rest of the country.

Tahir said the government should demarcate a separate graveyard somewhere in Srinagar, as many of them who have come from rural areas live in the city all their lives, and then in death, they have to go back. “When a transgender dies, it becomes difficult to take back the body to its native village,” she said.

One of the senior transgender and a known media face for the transgender community in Kashmir, Mohammad Aslam, 50, alias Bablooji, who lives in the Dalgate area of Srinagar with her family, said the government wasn’t paying any attention towards transgender in Kashmir.

“Transgenders, who are the residents of Srinagar city, have family graveyards but those who have come from other districts and left home 40 or 50 years ago do not have graveyards in the city,” said Aslam, who identifies as a transwoman.

Aslam said when her teacher Haji Ghulam Mohammad, a transgender originally from Kenihama village in Budgam district, died at the age of 90, his family didn’t show much interest in taking his body for burial in his native village. “My teacher had come to Srinagar when he was 15 years old and lived in Srinagar for 75 years but had not purchased a graveyard [plot] in the city even after living here for so many decades. When he died, we had to pool in money and buy land for his burial in the local graveyard,” said Aslam. According to her transgender people who have come from rural areas do not have a graveyard in Srinagar city, and there was a need for a burial place for them.

She said as the ownership of graveyards in Srinagar city was with locals, burying someone who had not already paid for a space was not possible there. “Nobody can even think of using any graveyard if he or she doesn’t have its inheritance or ownership rights” she said.

Dr Mansoor Ahmed, who is the first PhD scholar from the University of Kashmir to have worked on Kashmir’s transgender community, said most had no property rights in their father’s property.

“Even if the father has kept a share for the transgender child, it is never given to him or her when the father passes away. The connection with the biological family is mostly based on economics. If the family is getting some monetary benefit, they will stay in touch as most of the transgenders living in Srinagar are from rural areas.

“If there is no such benefit, the family will disown them even in death, as was the case of one transgender some years ago in Dalgate, Srinagar, who wasn’t allowed to be buried in the graveyard in Srinagar by locals. The transgender community had to buy the graveyard for the transgender and then bury him.”

Mansoor said most of the transgender had not got a share in their ancestral property in Kashmir. “Even if any transgender gets a share in the property, it would be a single room. I met one transgender person who was given one room in the house and that was doubled as his kitchen, bathroom and bedroom. In that room, he also accommodate people from his ‘baradari’, a term used by transgender for their community,” said Mansoor, who during his research has witnessed

He said there was a demand from them for a separate graveyard and a separate colony, but cautioned that it would exclude them more and add to their already burgeoning problems.

“Their visibility in society is less because they are facing a stigma due to their transgender identity. Instead of accepting them as a transgender, we see them as people trying to entertain us,” the post-doctoral fellow said.

Around 100 transgender community members whom Mansoor interviewed for his research told him that there should be a graveyard for them in Srinagar. “They are nowhere in the social, economic, political or cultural structure of society,” he said, adding there was a need for sensitisation and awareness among people.

Currently working as a postdoctoral fellow at the department of sociology, University of Kashmir, Mansoor’s thesis titled ‘Transgender Identity in Kashmir: A sociological Study’ threw light on the community’s problems, living status and arrangements and overall life of transgender in Kashmir.

“Even if they don’t want to leave home and live with their families, circumstances and discrimination within the family force them to leave their homes as they have no other option,” he said, adding they were being ridiculed in society so at the government level, a lot needed to be done.

When a transgender dies and their family is informed, they willingly or unwillingly have to take the body home for burial in the end even if the transgender hasn’t visited home for years. This also lets the family lay claim to the property that the transgender has accumulated all his or her life.

A young transgender person, Irfan Mir, 28, who is known by her sobriquet Mehak, said as they were in the business of matchmaking and singing and dancing, they preferred living away from their family. Mehak has bought a separate house in the old city Srinagar, where she lives with around 12 transgender persons, since 2010.

“I have bought two properties with my own hard earned money, including a big hall, where we can hold our functions or observe the mourning period of any community member who passed away. Seeing me do well, my family started calling me more often,” said Mehak, who feels a sense of satisfaction that her family consults her in every decision.

Mehak, who identifies as a transwoman, said if the family of a transgender is well-off, they give the property share but if the family is poor, the transgender will earn and help his or her family.

She said when transgender persons from rural areas come to Srinagar, they have no financial support from the family. “They may have land or property in the village but that is left behind. Most of them live on rent here in Srinagar and it is not possible for them to buy a graveyard plot in the city when the priority is to earn for a two-square meal,” said Mehak.

She said in most cases, when a transgender person dies, the family comes to take the body because they know he or she must have a good amount of money, household items, gold and silver and they could lay claim to it.

Mehak said they were thinking of buying a graveyard somewhere for the transgender community by pooling money with the help of those who were doing well.

The 28-year-old transwoman said while parents stay in touch out of love for their child, siblings of transgender persons usually stay in touch because they know they have monetary benefits. “When a transgender person dies, his or her siblings come to us to ask for the property they have accumulated. In death, they accept him or her because they know they have money,” she said, adding the relations in this world were mostly based on money.

Dr Aijaz Ahmad Bund, founder, Sonzal Welfare Trust, which works for the welfare of transgender, said most transgender members were denied property rights by their families.

“We know that they have been thrown out by their families, which means they do not even have the family ownership. This community may be in denial but we know the truth,” he said, adding none of them had ever come to him to help them get their share in the family property.

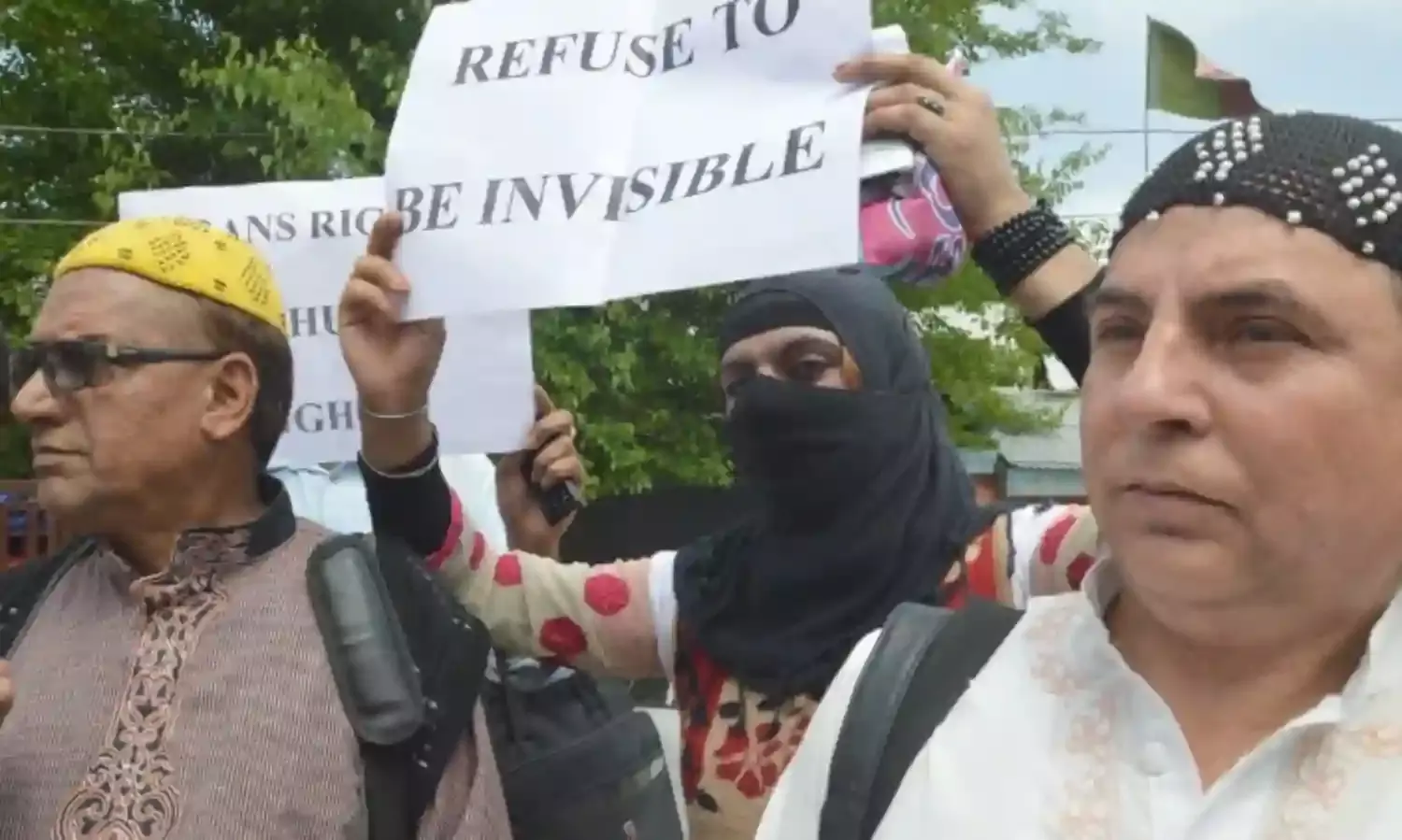

To provide for protection of rights of transgender people and their welfare, the Government of India has passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, but in Kashmir, transgender community continues to be neglected and marginalised.

“They are not ready to face their families because they have internalised shame and guilt. They feel the humiliation faced by their families is because of them,” the activist said.

Bund said the transgender community was not organised enough to handle an event like death on its own. “Their social structure is not so strong in Kashmir,” he said.

“The transgender population is living in a perpetual state of conscious victimhood. They know they are being violated and victimised and they have kind of normalised it. The violence, abuse and discrimination that they go through starts from home only. transgender identity doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is already othered and marginalised” said Bund, who has been working as a transgender activist since 2011, adding the.

Bund, who has worked extensively with Kashmir’s transgender community, maintains a record of people he has worked with. This includes their age, parentage, present address, native residence, academic qualification, occupation, current living arrangement, assets, tenure of migration from their native villages and documents such as Aadhaar card, ration card, election card, passport and identity card and contact information. In most of the forms, the space near the assets on the forms reads, “property denied”.

Bund said most transgender people who lived with their families in Srinagar do so because they earn and take care of the family, and own property. So in those cases there are least chances of them being evicted. “The relationship they share with their families is purely economical,” said Bund.

He said when Nadeem Ahmed Ganai, a transgender in his 30s died of brain haemorrhage in 2018, his family had categorically refused to take the body. “When we called the family, they said he had brought disrepute to them all his life so they cannot take the body. I can never forget the words that his family said,” said Bund.

Ganai was from south Kashmir’s Anantnag district but was living in a rented accommodation in Srinagar since he was 10 years old.

“After the father and the brother refused to take the body, we contacted his sister. It was after a lot of persuasion that the sister agreed, with a caveat that no transgender person would accompany the body to Qazigund in Anantnag district,” said Bund, adding the case is documented as the body was sent for a post-mortem and was lying at the local police station for the whole day after the family was not ready to take the body home for burial.

The community members know that asking for their share in the property would mean shutting the door on the relations and being cut off completely. For most of them who are not from Srinagar, the property as well as the graveyards are the ones they have in their villages.

In Kashmir, locals buy land for family graveyards. There is no government land to bury the dead. The graveyards are also handed down from one generation to another unlike in the rest of India.

Kashmir’s transgender are a marginalised community who live in clusters or alone away from their families. Disowned by their families, they have nothing to call their own.

Most of them leave their home early on in their formative years, robbing them of all rights that they are entitled to. Left to fend for themselves and pushed to the peripheries of society, they have no social security.

“The social welfare department had decided to pay Rs 1000 as an old-age pension to transgender people above the age of 60 years. But that involves a lot of paperwork so most do not want to go through that grind. Neither the state government nor the Central government has done anything for us. The government only remembers us at the time of elections,” said Aslam.

She feels the government should at least demarcate some land for a graveyard in the city as it wasn’t possible for a transgender to buy land for burial when the land rates were skyrocketing.

As per the Census of 2011, Jammu & Kashmir has more than 4,000 transgender people. A majority of them have been disowned by their families due to the taboo associated with being the third gender.

Most of them work as matchmakers and dance at weddings. As age catches up with them, work dries up. Old age for them is a curse as it brings poverty and there is no one to look after them in the absence of family.

Most of the graveyards in Srinagar have been used for generations, in designated places. As the transgender community lives from hand to mouth most days, buying land for burial is not even on the list, when the daily fight is to earn for food to keep going.

The taboo attached with the third gender is the reason why most families disown them in life and sometimes even in death.

Former head of the department of history, University of Kashmir, Prof Bashir Khan, who said there was a need for various organisations and ‘anjumans’ to come forward and help the transgender community of Kashmir. Such organisations are already operating in the rest of the country.

Prof Khan said in other states, there are cemeteries provided by the government where Muslims bury the dead, but in Kashmir people have to buy land for burial. “It is unfortunate that people have to buy land for burial in Kashmir. The concept of cemeteries in other states could have been replicated in Kashmir given the paucity of land,” Prof Khan said.

Khan said transgender community in Srinagar were facing a lot of problems and were looked down upon in their own families and even in society. He said as Muslims, people do not give much credence was not given to property rights.

“We have not accepted transgender people wholly and that shows in mosques for instance. I have not seen any transgender offering prayers in a mosque in my life. This could be because people do not like to pray in close proximity with them or they themselves do not want to enter the mosque knowing what problems they will face”.

He said more than the common people, it was the responsibility of the religious elite and political elite to do something to uplift the transgender community. He added there was a need for intervention from the government so that members of the transgender community could through various initiatives be provided graveyards and other facilities.

The story was reported under NFI Media Fellowships for Independent Journalists.