Indian Cinema Invisiblizes The Sex Worker

Taalash- The Answer Lies Within

Rima Kagti’s Talaash (2012) which features sex workers not for their titillating characteristic but as victims of circumstance, where some want to go out of the profession while the rest remain because the world of sex workers does not offer either a choice or an exit point.

Talaash – The Answer Lies Within is not an ideal choice that throws up adequate space to study the sex worker as a working woman and her position or the lack of it in the nether world she occupies, which many Indian films directed by men offer. But this was taken because it sheds light on a hitherto tragic part of the sex-worker’s life.

The most powerful statement Rima Kagti makes through Talaash – The Answer Lies Within is the absolute “disempowerment” of a woman who becomes a sex worker. Her “work” identity barely provides her with the bare necessities of life and nothing more. Once she steps into the trade mainly by force of circumstance, she is reduced to a bonded slave and has no respite. If she is trapped in a police arrest along with other girls; the staff in the jail often force her to sleep with them without paying for the service.

So, the sex worker in films or in real life, does not have any power or control over her life or her work or her income till death releases her from the bondage. There is no dignity in her work, her life and most tragically, in her death. If one follows the film closely, all this, and much more, are unfolded through the character of Rosie/Simran.

The financial exploitation and poverty are not hinted at in the film which is not really a part of the story. But it would have helped understand the tragedy of working women like Rosie whose “date of expiry” is forever threatening her very existence.

The circulation of money and its abstraction as a sign in a system of exchange serves as a mirror image for woman as a sign in a system of exchange. Ironically, women who form the very commodity that is exchanged, have little or no control over the money that is exchanged. Nor do they have access to the circulation of money.

The large number of pimps, musclemen, self-appointed protectionists within and without the legal machinery, the brothel madams and the local politicians form an unending link in a chain of middlemen who cut into the meagre earnings of the prostitute placing her back to the poverty she began from.This circular reality of poverty offers the tragic irony of her existence.

Through Rosie, Kagti tells us that If a sex worker’s death is accidental or murder or suicide, or, if she suddenly goes missing, no one knows, because no one cares whether she lives or dies and no one performs her funeral rites. Besides, she never existed so how can a woman who never existed, die? This is the bottom line of Talaash – The Answer Lies Within that comes across in the end when one realises what the real mystery behind the uncanny “accidents” is all about.

For the estimated more than three million sex workers in India other than the travails of informality, they are further marginalized along two other axes. One is the cloud of criminality associated with their occupation (2), which gives the law an unnatural power over them and is used brutally by local police to threaten, harass and routinely extort money and sexual favours. This semi-underground status precludes them from accessing the legal system for recourse to the discriminations they live with every single day.

The other is the underlying strain of morality that keeps them outside mainstream limits, keeps them ghettoed in ‘red light areas’ and envelops them in a stifling social stigma that justifies public misbehavior towards them, social ostracism, eviction from prime properties and exclusion from health services or access to education for their children.

The three sex workers present three different facets of the profession. Mallika has been “rescued” and purchased by her lover Shashi. But Shashi is a pimp who keeps living with her within the same brothel. He treats her very badly and is not married to her. Besides, he is a pimp that means that there is no guarantee that he will not push her back into sex work all over again once his crush is over. When Shashi dies, she is pulled back against her wishes into the same trade. If Surjan saves her, it is no act of courage on his part but it has been motivated by his strange friend Rosie, who says she does not need to be “rescued” to lead a better life which is not easy, but suggests that he save the poor Mallika from her terrible condition.

The slightly elderly prostitute who Tehmur fills with unreal dreams of a moneyed future is a tragic figure of a once-in-demand sex worker who does not believe in the promises made by Tehmur who is himself in dire straits. So, though she finds a route of escape as the train in which she was supposed to escape to a different future begins its run, she begins to weep uncontrollably as she now knows that Tehmur will not come. The bag filled with money lies near her feet.

Rosie, also known as Simran as sex workers have several names, is out on a revenge spree because her three clients allowed her to bleed to death though they could have saved her because taking her to a hospital would have created a scandal as Armaan Kapoor was a high-profile celebrity. They saved the friend who fell along with Rosie though, for the rest of his life, he remains chained to the bed not able to move or talk or even recognize people.

But they did not bother to save Rosie and left her to die on a deserted street in the middle of the night. Ironically, Rosie defines the moral fabric of the entire story of several dysfunctional individuals brought together through completely different tragedies of their own. Surjan digs out the skeletal remains of the dead Rosie who was buried clandestinely by Shashi and performs her last rites – alone. He recognises her from the large ring she always wore and finds her by the sea where the three ‘accidents’ happened and she always said was “my space.”

So, revenge for a sex worker happens only after she is dead, not before. This suggests that Rosie is a woman who draws strength from her death as a ghost. This gives Surjan the rationale to accept his wife’s explanation of the seances she goes through with the Parsee neighbour and when he finds an envelope with “Dadda” written in Karan’s hand in a drawer. This however, is the weakest link in Rima Kagti and Zoya Akhtar’s script which does not permit the estranged couple to reunite naturally but falls back on unexplainable phenomena that lie beyond any scientific argument to bring them together.

The film insists all along that Surjan does not believe in occult practices and seances so one has to bring the ghost of a dead sex worker to avenge her death for him to believe in ghosts and in occult practices and this brings the fragmented couple together. It is a sad comment on the film that does not give enough footage to Rosie which would have strengthened the cause of the sex worker who is the least empowered among all working women across the world.

Rosie, Mallika and the other women are all working women. But sex work does not have any legal sanction. So, they have no Aadhaar Card, no Ration Card, no Pan Card and no Voter’s Identity Card. They have no contractual agreement for their work, no pension and no retirement benefits. Nor do they have a birth certificate and rarely if ever, a death certificate. In other words, there is no proof that they exist and therefore, there is no proof of their death. When Surjan Singh Sekhawat asks Rosie why there was no investigation when a sex worker went missing, Rosie says, “Why would anyone bother?”“Why did anyone not look out for the missing woman?” he asks and her answer is, “how can a woman who did not exist go missing?”

One merit in the narrative lies in not dwelling upon the back stories of any of the characters in the red-light areas but underlines the back story in the lives of the mainstream characters of Surjan and Roshni, separately and together. Sadly, the entire film is focussed on Surjan Singh Sekhawat and his problems – personal and political and the other characters are reduced to shadowy figures needed to strengthen his back story. In other words, Talaash is much more about Surjan Singh Sekhawat than about his wife Roshni or the elusive intriguing woman in his life called Rosie.

One must unfortunately point out that no Indian film-maker either from parallel cinema or from the mainstream has dealt with prostitution as a basic socio-economic problem of a capitalist, patriarchal society. There has been no attempt, in any guise whatsoever, to deal with the basic problems that nag the prostitute - medical assistance, drug, STD and AIDS programmes, or with the decriminalisation of the prostitute.

In practice, she continues to bear the brunt of punitive law-enforcement measures and legal strictures. Public opinion does not condemn the prostitute in condemning prostitution. She is the most visible figure, the central agent of the system and as such, the invariable target of police, judges, law-makers, the State and even social reformers.

At the same time, she is rendered ‘invisible’ in real terms because so far as her economic identity is concerned, her contribution to the nation's GDP is not counted as she does not “exist.” The truths that ultimately come out are: that the buyers are seldom punished or convicted, even when they are guilty under the law. They repeatedly insist that “the law isn't for people like us” even in films. They are right. Integration and rehabilitation of the prostitute in cinema have been few and far between.

The most significant question that arises in all this is that – does this not make the director and scriptwriter Rima Kagti and Zoya Akhtar equally culpable in marginalising and rendering the sex workers “invisible” – in terms of footage, visual presence, plot and theme -factors they have actually aimed to demonstrate and attack in and through the film? Rosie has very little footage in the entire film and this dilutes the significance of her existence as a surreal figure. Does this not make Kagti and Akhtar equally complicit in marginalizing the sex workers that they are critiquing the society of doing?

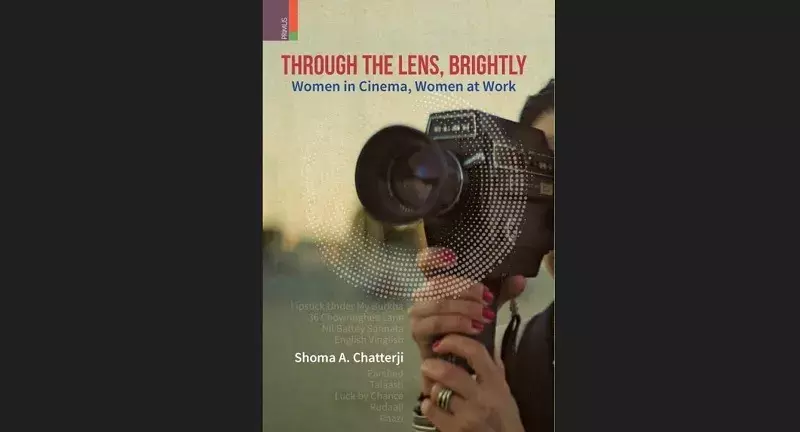

This is an extract from the author’s book THROUGH THE LENS, BRIGHTLY – WOMEN IN CINEMA, WOMEN AT WORK, Primus Books, Delhi, 2023. This book written by SHOMA A.CHATTERJI was included in the four-books shortlist entered for the MAMI 2024 Best Book on Cinema Award. The book is an in-depth exploration of how women directors have represented working women in their feature films and whether this work-identity has empowered these women or not.

The most significant question that arises in all this is that – does this not make the director and scriptwriter Rima Kagti and Zoya Akhtar equally culpable in marginalising and rendering the sex workers “invisible” – in terms of footage, visual presence, plot and theme -factors they have actually aimed to demonstrate and attack in and through the film? Rosie has very little footage in the entire film and this dilutes the significance of her existence as a surreal figure. Does this not make Kagti and Akhtar equally complicit in marginalizing the sex workers that they are critiquing the society of doing?