Sanjay Nirupam Threatens “Jallianwala Bagh Type of Situation”

April 13 - Anniversary of the gruesome massacre

In a chilling statement that reverberated across India, Sanjay Nirupam, a prominent Mumbai politician from the Eknath Shinde-led Shiv Sena, warned Muslims that agitating against the Waqf (Amendment) Bill, as they did during the 2019-20 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests, could lead to “a Jallianwala Bagh type of situation.”

The remark, widely covered by the media, evoked the brutal massacre of April 13, 1919, when British-led troops gunned down 379 unarmed Indians peacefully protesting colonial rule in Amritsar’s Jallianwala Bagh.

The timing of Nirupam’s threat—coinciding with the historical resonance of that date—lent it an especially ominous tone.

Nirupam was responding to the All-India Muslim Law Board’s declaration that passage of the Waqf Amendment Bill would spark nationwide protests akin to those at Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh against the CAA.

The 2019-20 demonstrations had symbolized resistance to policies perceived as discriminatory, but Nirupam’s invocation of Jallianwala Bagh—a colonial atrocity—recast the spectre of violence in a starkly different context: a domestic conflict pitting Indians against Indians along religious lines.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre unfolded against the backdrop of India’s freedom struggle. On April 13, 1919, around 5,000 men, women, and children gathered in the enclosed garden to protest the repressive Rowlatt Act and the arrests of Congress leaders, Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew, a Muslim Barrister, and Dr. Satyapal, a Hindu medical doctor.

Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, commanding the Amritsar cantonment, ordered his troops—comprising Gurkhas, Pathans, and Baloch soldiers—to seal the exits and open fire. In a relentless 10-minute barrage, 1,650 rounds were unleashed, killing 379 and injuring 1,200. The firing targeted the few narrow exits, trapping the fleeing crowd in a hail of bullets.

The slaughter, unprecedented since the 1857 revolt, galvanized India’s independence movement. A horrified Rabindranath Tagore renounced his British knighthood, and in 1920, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Non-Cooperation Movement. Hindus and Muslims stood united in this fight against foreign oppression, exemplified by the leadership of Kitchlew and Satyapal.

Yet Dyer remained unrepentant, later writing that dispersing the crowd without bloodshed would have made him “a fool,” and insisting India was unfit for self-rule.

Contrast this with Nirupam’s threat. Where Jallianwala Bagh was a colonial assault on a united Indian front, his words signal a modern rupture—an attempt to suppress a minority community under the guise of national interest. This shift mirrors a broader transformation in Indian nationalism. Once a peaceful crusade against foreign rule, it now often glorifies division and violence against fellow citizens.

The reverence for Nathuram Godse, Gandhi’s assassin, and the applause for Pooja Shakun Pandey’s 2021 call at a Haridwar Hindu conference to kill Muslims to “protect” India underscore this dark evolution.

“If 100 of us become soldiers and are prepared to kill 2 million Muslims, we will win,” Pandey declared to a cheering crowd, openly advocating genocide.

The prelude to Jallianwala Bagh also reveals the complexity of that moment. A nationwide hartal called by Gandhi in early April 1919 had sparked unrest, alarming British authorities already unsettled by Hindu-Muslim unity.

In Amritsar, the deportation of Kitchlew and Satyapal incited protests, culminating in violence—eight killed by troops, government buildings torched, and British civilians attacked, including Marcella Sherwood, who was rescued by locals.

Dyer’s response was disproportionate and merciless, extending beyond the massacre to punitive measures like forcing residents to crawl on their bellies in public streets—a humiliation he justified as reverence for British authority.

In Britain, reactions varied. The Morning Post hailed Dyer as “the man who saved India,” raising over £26,000 for him, while Winston Churchill condemned the massacre as a “monstrous event” without parallel. The Labour Party demanded accountability, but Dyer doubled down, insisting India’s stability required a firm colonial hand.

Today, Nirupam’s rhetoric reflects a nationalism no longer defined by unity against an external foe but by the subjugation of an internal “other.”

The Waqf Bill, like the CAA, has become a flashpoint in a polarized landscape where dissent is met not with dialogue but with threats of historical violence. Indian nationalism, once a beacon of peaceful resistance, now risks being overshadowed by calls to dominate, divide and unleash violence.

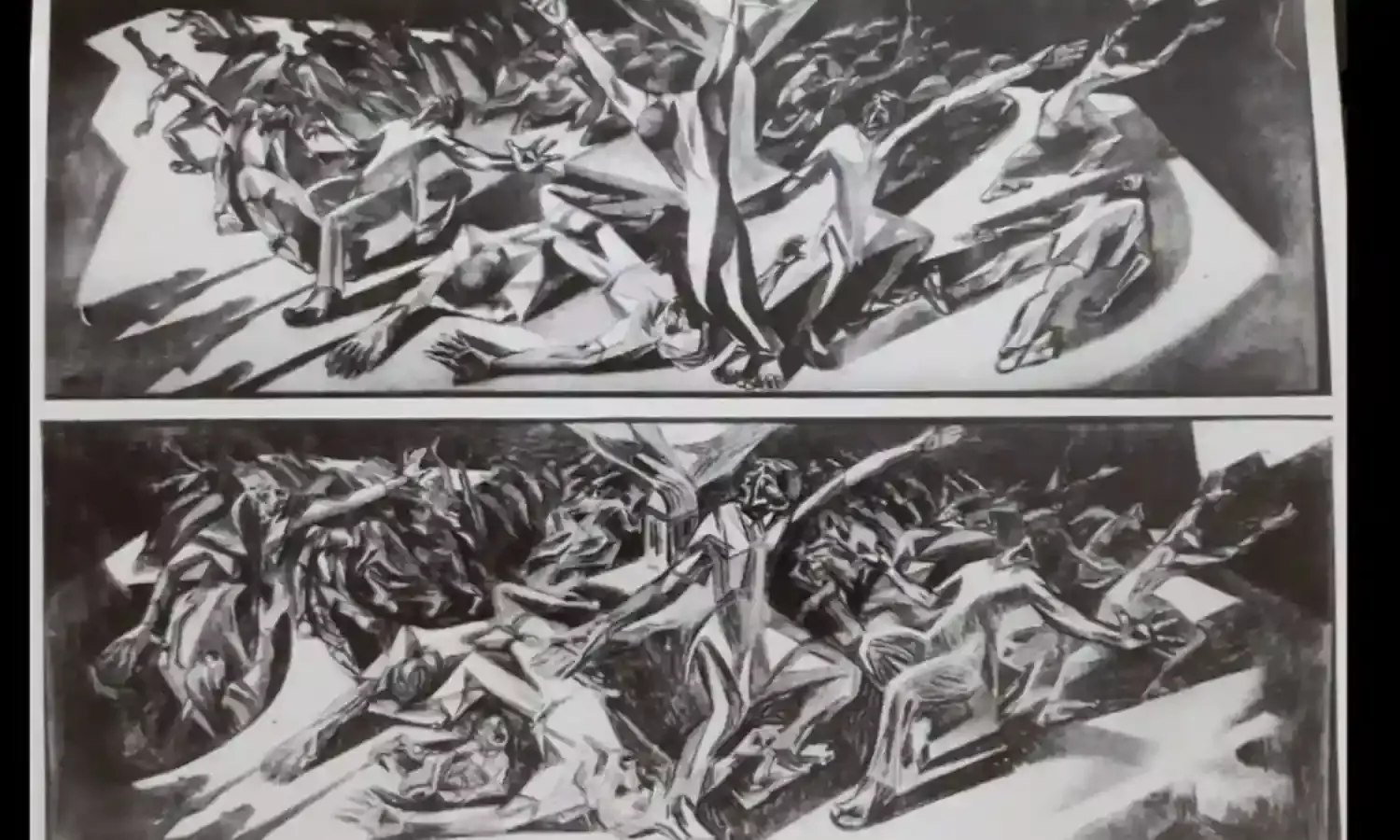

Cover Photograph: Jallianwala Bagh sketches pencil and charcoal by artist P.N.Mago.