Who Is Afraid of Books?

Cops seem to have shed all pretensions

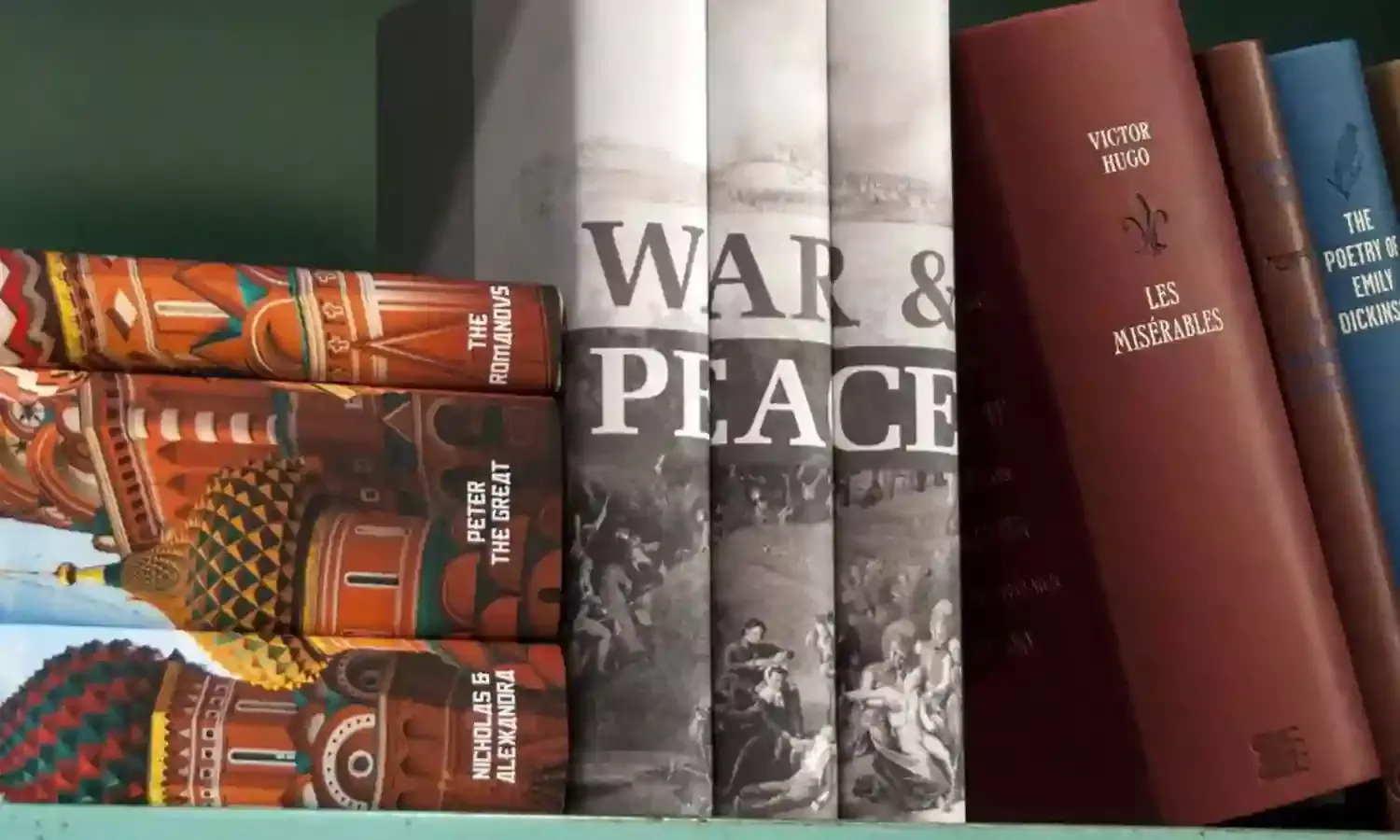

The clarification that it was not Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace, but a little known title "War and Peace in Jungle Mahal" authored by a journalist that was found objectionable by the police among other 'incriminating documents' in the much publicised case does little to cheer one up.

Historically, rulers have always had a strange love hate relationship with books. Personally some of them could be scholars or great connoisseurs of books, but when it came to books that questioned their wisdom or policies, they had no qualms in even burning down every copy, besides throwing authors into the dungeon.

During our freedom struggle, keeping certain books in the house could land one in very serious trouble with the law. The colonial government regularly proscribed books, which its agencies thought could promote among the subjects disloyalty to Her Majesty, or even instigate them to raise war against the state. If a suspect was a member of any party opposed to the government, recovery of proscribed books from that person was enough to prove a charge of sedition. Still, in general the police then would look only for books that were officially proscribed.

In independent, democratic India, the police seems to have shed even that pretension.

During the '70s when the Naxalite movement spread like wildfire among the students and youths in West Bengal, possession of any book on communism was severely frowned upon by the police. And if one had a copy of the little "red book", there was no escape from arrest, painful interrogation and, ultimately, incarceration for long periods. It appears that the situation has changed little since then.

India can be really proud of a publication industry that produces hundreds of titles every day on all conceivable subjects. There must be readers who buy most of those books; otherwise, the industry cannot be as thriving as it visibly is.

I do not think any of these titles are proscribed by the authorities. If they were, the publishers would not market them. Still, possessing a copy of a book - proscribed or not - seems to be fraught with danger if it deals with subjects that the authority has reason to suspect has the potential to 'foment trouble' or points to the possessor's sympathy with groups inimical to the government. If the book reveals or even hints at some unpalatable truths about certain actions of the government, it likely would spell doom for the possessor.

The thought scared me a bit and made me look at my own humble collection to see if there was anything that could link me to the ideologies that the government is not enamoured of. My retirement days are divided between Delhi and Kolkata. So are my books. I have a few in my flat in Delhi, some in my ancestral home in north Kolkata and a few more in my apartment in Kolkata's northern fringe.

I find in Delhi I have several books on Indian history, including a volume by Romila Thapar. God, will they believe that I had bought that book decades ago as a supplementary reading material on Indian history, and not because at that time I knew anything much about the renowned professor and her tryst with the establishment? I am also somewhat doubtful about how works of Nehru, Subhas Bose and Chomsky, and a nice collection of essays on nationalism by well-known critics of the establishment in my collection would be viewed.

Fortunately, I also have several books on the life of Shri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, and a wonderful book on India's contribution to the world by Max Mueller, The Gita in Bengali as well as in English, and a collection of lectures by a renowned monk. These and the five volumes of Mahabharata in Bengali, I earnestly hope, would bolster my Indian credentials.

In Kolkata flat the entire collection comprises of Tagore's works and those on his life, besides books by different authors on miscellaneous subjects. These should pass the test, although Tagore's idea of India's unity in the midst of diversity is not particularly liked by the present day leaders and their bhakts.

If, however, the decaying, moth-eaten books in my ancestral home are a guide, then I have perhaps no escape. There, books on political science and international relations - reminders of the midget's efforts to touch the sky - and several volumes of Marx and Lenin co-exist with Edgar Snow.

The War and Peace, and several volumes of Gorky, Chekov, and other Russian authors vie for space with Conan Doyle, Poe, Wodehouse and others. In my school days Russian books were dirt cheap, courtesy the publicity department of the then USSR. That explains the preponderance of the famous Russian authors in my collection, rather than any particular affinity for that country.

Frankly, the books by Marx, Lenin are not mine. They were my elder brother's, who was an active trade unionist in his service life. The books were briefly transferred to his union library in 1971 and later brought back home when things cooled down. I merely signed my name on them at some later date!

The aim of writing all this is not to tell the reader at length about my quite insignificant collection of books. It is rather to say that anyone trying to read my mind through the books I possess will be totally confused. And I am sure, most general readers would fall in my category. In fact, unless one is a scholar in a particular subject, or is a staunch follower of a particular line of thinking, one is bound to possess books on a variety of subjects. They are likely to indicate, more than anything else, how the reader's interest changed course from adolescent to adulthood and beyond.

As long as the books are not proscribed, and are available on the shelves of bookstores, the readers should be free to possess them. It will indeed be a sad day for this country if possession of books that present a point of view contrary to that of the ruling dispensation, or even of the majority, is frowned upon or the reader's loyalty to the nation is questioned on the basis of books he reads.

Sandip Mitra retired from the Ministry of External Affairs,GOI.