Once on a Time in Mowgli’s Kingdom…

Kipling writes of Seeonee, a place I had crossed many times

Moving in the dreamland of Pench, you cannot be blamed for daydreaming of meeting Mowgli, jumping before you from a tall tree, or skipping past with Baloo.

Baloo, the bhaalu or bear, is an expert in jungle rules and teaches it all to Mowgli.

Did Mowgli, once the English world’s most loved character figuring in The Jungle Book, really exist? Was he only a figment Rudyard Kipling’s imagination?

The picturesque Pench National Park in Seoni - spelt Seeonee in The Jungle Book - Chhui and Amodgarh, located in the Satpura Mountain range in Madhya Pradesh, may perhaps answer these questions.

The Jungle Book just turned 125 years old, young at heart with Mowgli remaining unchanged since he was fathered by Kipling in 1894.

Feral children like Mowgli are studded across literature, history and mythology, be it Tarzan or Hagrid or the wolfboys Romulus and Remus, supposed founders of Rome.

First published in 1894, The Jungle Book centres on the feral child Mowgli and animals like Bagheera the black panther, and the evil Shere Khan, self-styled king of the tigers of Pench, who behaves like today’s politicians.

Like the so called leaders of mankind’s political jungles, always ready to pounce upon their rivals, Shere Khan too tries to attack Mowgli who is more popular than he in the jungle kingdom of Pench, with a much larger fan following among the animals.

Mowgli, of course, remains very popular among the human cubs of the world’s urban concrete jungle.

Strangely enough, the two India-born British writers both of whom were journalists – Kipling and George Orwell – created miracles in the literary world with their books based on animal characters: The Jungle Book, and Animal Farm.

As a journalist working in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and the Vidharbha region of Maharashtra for a long period, I passed through Seoni innumerable times by road between 1994 and 2006 but never visited the Pench forest.

In November last I stayed in Seoni for three days, especially to do some research on five characters: Mowgli, two ancient lovers Bilkis Bano and Capt. John Longman, the dreaded Thugee lord Ajmal Sheikh and his ferocious follower Ramdin Pandey.

I roamed around Amodgarh and little hamlet Chhui to enquire about them as they have very close connections with these places. Besides, The Jungle Book says caves, hillocks and jungles here were the favourite places of Mowgli and his friendly jungle pack.

Interestingly, Sir William Henry Sleeman, in charge of the Thugee Repression Cell of the East India Company, also camped in these areas for quite some time to hunt Thugees.

It was near here that a feral child was captured in 1831. Did he inspire Kipling?

Incidentally, Kipling also wrote about the Thugees, for which the Satpura Mountain Range was infamous, in his long poem Gunga Din.

The Pench Forest, Seoni, Chhui and Amodgarh were Thugee dens during Sleeman’s days.

The story of Bilkis and Capt. Longman, however, dates back to 1818 when the East India Company established its rule in the entire area of what is Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Vidharbha today.

I first heard about Bilkis and Capt. Longman in 1996 in Nagpur from Pandey Ji (forgotten his first name).

The great-grandson of a dreaded Thugee active in the Satpura Mountain Range, grandson of a Haka-man and son of an alcoholic vehicle driver frequently losing job for roadside accidents caused by his drunk-drives, old Pandey Ji served an English daily much older than him.

It is published from Nagpur.

I served that daily as a Roving Correspondent thus crisscrossing the Vidharbha-MP-Chhattisgarh region, often passing through Seoni.

Pandey Ji, who must have been 75 years old at the time, was a do-all, perform-everything sort of an employee though his official designation was Chuprasey or orderly. He commanded respect from everybody, including the Editor and newspaper owner’s son.

He was an expert storyteller who knew everything about Pench-Seoni-Amodgarh-Chhui as his family had lived in Chhui for over 300 years.

He told me his family members saw the wolf-boy captured in 1831 by Sleeman.

The boy, however, did not survive long. This is something that also happened to the two feral girls, named Kamala and Vimala, found in Bengal about a century ago.

After hearing Pandey Ji’s stories about that wolf-boy, and Bilkis, Capt. Longman, Ajmal and Ramdin Pandey, I became intensely curious to know more. But I had to wait for long to do further research.

I often doubted, and still doubt, if Pandey Ji was by any chance related to Ramdin Pandey, the dreaded Thugee.

Pandey Ji said that as a child he had heard stories about the feral child, and the love tale of Bilkis and that Firangi army captain, from his grandfather who was a Haka-man of the Shikar Party of British Sahibs who often came to these parts of Hindoostan of the British Raj to hunt tigers.

His grandfather, being Haka-man, beat canisters to force a tiger come out of the jungle scrub, helping the British Shikaris moving on elephants to shoot the lord of the jungle.

In those days, Haka-men were indispensible for Shikar. They are the beaters, who make loud sounds to force animals out of hiding.

Many a time, tigers suddenly pouncing from bushes would attack them and flee much before the Firangis could shoot them.

Sometimes, Haka-men died also.

At a little distance from the hamlet of Chhui, the East India Company set up a small military post with Capt. Longman as its in-charge in 1818.

The Thugee lord Ajmal supplied rice, wheat, meat, oil and vegetables to that military post. The Thugees were expert in assuming different appearances, posing as traders and even Sadhus for information on the movement of British troops in their anti-dacoit operations.

They took precautions accordingly.

At the time the Pench forest in Seoni-Amodgarh-Chhui housed several Thugees, but the common people hardly knew as they were very articulate, helpful, well behaved and suave in their public behaviour.

When the chance came, they would suddenly bring out a Reshmi Rumaal (silk sash) with a coin attached to its centre and wind it around their victims’ neck. The coin fastened to it put more pressure on the throat and quickly broke it.

Once, riding his horse, Captain Longman saw the face of Bilkis, the young Bibi of Ajmal, when she removed her veil for a few minutes to talk to someone. She saw him too.

Both were young and both fell in love. A deadly liaison, indeed!

We know what happened next: Frequent secret meetings in the jungles of Chhui. But her activities did not escape the eyes of Ajmal’s most trusted man, Ramdin Pandey.

The Thugees knew only one punishment for betrayal: murder.

Naturally, Ajmal condemned the lovers to death, but he said nothing to Bilkis. From his behaviour she would guess nothing.

In one such jungle rendezvous, as the lovers were busy talking, maybe planning their marriage or Bilkis’ escape to the residence of Capt. Longman, they did not know that Ramdin Pandey and Thugee Niyamat Khan were watching then.

The lovers were lost in their own world. Suddenly, the captain fell on the ground. A spear had pierced his heart.

Before Bilkis could realise what had happened, a spear pierced her too.

They had to die. And they did!

The authenticity of the story may be doubtful as nobody in Chhui or Amodgarh, which now lacks people of the older generation, could confirm it, but it is a good Bollywood movie plot.

In Kipling’s India the Thugees were active across Hindustan.

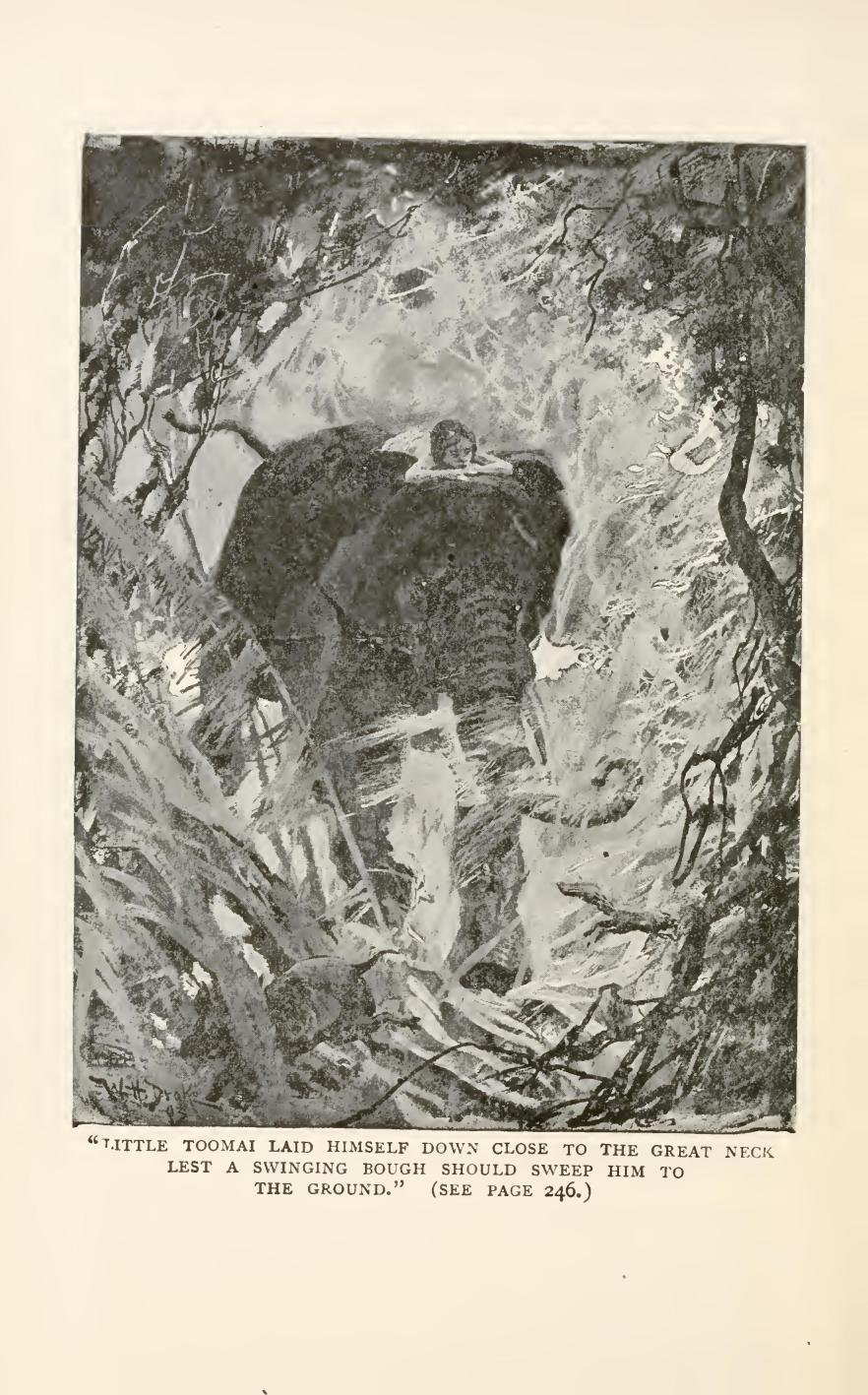

Kipling perhaps followed the facts on the real-life feral child caught by Lt. Moor in 1831 and detailed by Sleeman in his pamphlet, An Account of Wolves Nurturing Children in Their Dens.

Years after The Jungle Book was published, a Christian priest named J.A.L. Singh claimed in 1918 to have rescued two little girls from the jungles in today’s Midnapore district of West Bengal, whom he named as Amala and Kamala.

A British newspaper, The Westminster Gazette, published it very prominently. The report created a massive sensation in England.

Who knows, perhaps Mowgli may have been a reality in the jungle regions of Pench?

The Jungle Book (1894)

Mowgli’s Brothers

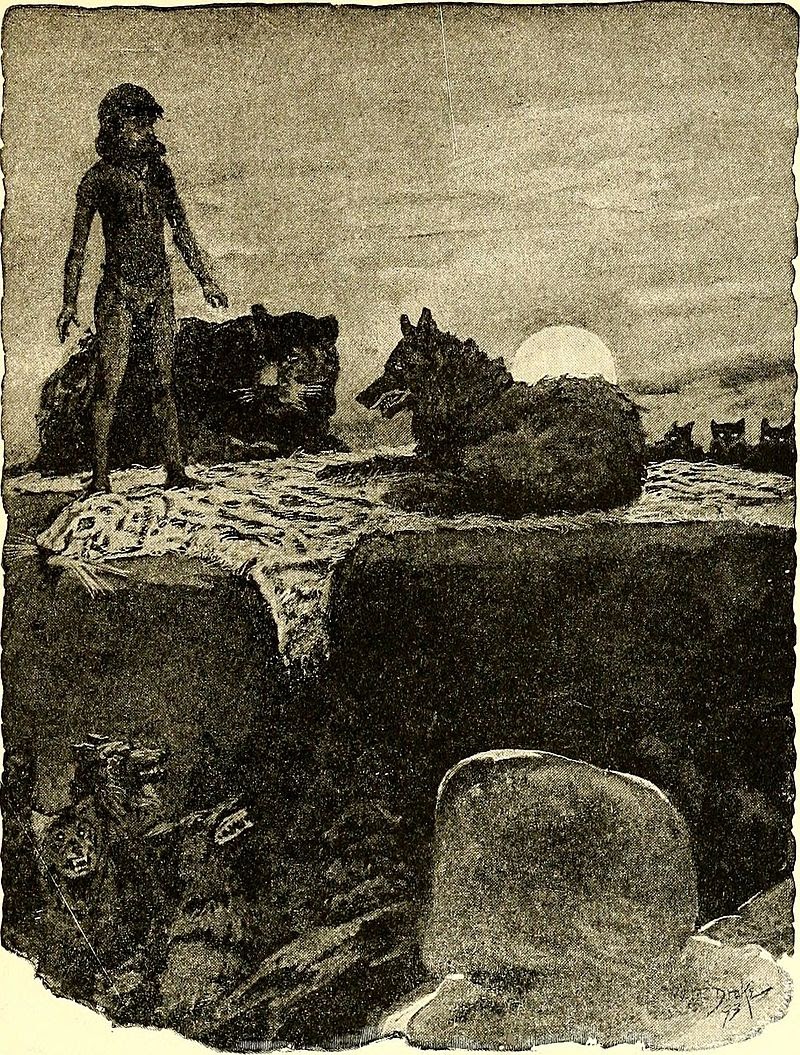

It was seven o’clock of a very warm evening in the Seeonee hills when Father Wolf woke up from his day’s rest, scratched himself, yawned, and spread out his paws one after the other to get rid of the sleepy feeling in their tips. Mother Wolf lay with her big gray nose dropped across her four tumbling, squealing cubs, and the moon shone into the mouth of the cave where they all lived. “Augrh!” said Father Wolf. “It is time to hunt again.” He was going to spring down hill when a little shadow with a bushy tail crossed the threshold and whined: “Good luck go with you, O Chief of the Wolves. And good luck and strong white teeth go with noble children that they may never forget the hungry in this world.”

It was the jackal—Tabaqui, the Dish-licker—and the wolves of India despise Tabaqui because he runs about making mischief, and telling tales, and eating rags and pieces of leather from the village rubbish-heaps. But they are afraid of him too, because Tabaqui, more than anyone else in the jungle, is apt to go mad, and then he forgets that he was ever afraid of anyone, and runs through the forest biting everything in his way. Even the tiger runs and hides when little Tabaqui goes mad, for madness is the most disgraceful thing that can overtake a wild creature. We call it hydrophobia, but they call it dewanee—the madness—and run.

“Enter, then, and look,” said Father Wolf stiffly, “but there is no food here.”

“For a wolf, no,” said Tabaqui, “but for so mean a person as myself a dry bone is a good feast. Who are we, the Gidur-log [the jackal people], to pick and choose?” He scuttled to the back of the cave, where he found the bone of a buck with some meat on it, and sat cracking the end merrily.

“All thanks for this good meal,” he said, licking his lips. “How beautiful are the noble children! How large are their eyes! And so young too! Indeed, indeed, I might have remembered that the children of kings are men from the beginning.”

Now, Tabaqui knew as well as anyone else that there is nothing so unlucky as to compliment children to their faces. It pleased him to see Mother and Father Wolf look uncomfortable.

Tabaqui sat still, rejoicing in the mischief that he had made, and then he said spitefully:

“Shere Khan, the Big One, has shifted his hunting grounds. He will hunt among these hills for the next moon, so he has told me.”

Shere Khan was the tiger who lived near the Waingunga River, twenty miles away.

“He has no right!” Father Wolf began angrily—“By the Law of the Jungle he has no right to change his quarters without due warning. He will frighten every head of game within ten miles, and I—I have to kill for two, these days.”

“His mother did not call him Lungri [the Lame One] for nothing,” said Mother Wolf quietly. “He has been lame in one foot from his birth. That is why he has only killed cattle. Now the villagers of the Waingunga are angry with him, and he has come here to make our villagers angry. They will scour the jungle for him when he is far away, and we and our children must run when the grass is set alight. Indeed, we are very grateful to Shere Khan!”

“Shall I tell him of your gratitude?” said Tabaqui.

“Out!” snapped Father Wolf. “Out and hunt with thy master. Thou hast done harm enough for one night.”

“I go,” said Tabaqui quietly. “Ye can hear Shere Khan below in the thickets. I might have saved myself the message.”

Father Wolf listened, and below in the valley that ran down to a little river he heard the dry, angry, snarly, singsong whine of a tiger who has caught nothing and does not care if all the jungle knows it.

“The fool!” said Father Wolf. “To begin a night’s work with that noise! Does he think that our buck are like his fat Waingunga bullocks?”

“H’sh. It is neither bullock nor buck he hunts to-night,” said Mother Wolf. “It is Man.”

The whine had changed to a sort of humming purr that seemed to come from every quarter of the compass. It was the noise that bewilders woodcutters and gypsies sleeping in the open, and makes them run sometimes into the very mouth of the tiger.

“Man!” said Father Wolf, showing all his white teeth. “Faugh! Are there not enough beetles and frogs in the tanks that he must eat Man, and on our ground too!”

The Law of the Jungle, which never orders anything without a reason, forbids every beast to eat Man except when he is killing to show his children how to kill, and then he must hunt outside the hunting grounds of his pack or tribe. The real reason for this is that man-killing means, sooner or later, the arrival of white men on elephants, with guns, and hundreds of brown men with gongs and rockets and torches. Then everybody in the jungle suffers. The reason the beasts give among themselves is that Man is the weakest and most defenseless of all living things, and it is unsportsmanlike to touch him. They say too—and it is true—that man-eaters become mangy, and lose their teeth.

The purr grew louder, and ended in the full-throated “Aaarh!” of the tiger’s charge.

Then there was a howl—an untigerish howl—from Shere Khan. “He has missed,” said Mother Wolf. “What is it?”

Father Wolf ran out a few paces and heard Shere Khan muttering and mumbling savagely as he tumbled about in the scrub.

“The fool has had no more sense than to jump at a woodcutter’s campfire, and has burned his feet,” said Father Wolf with a grunt. “Tabaqui is with him.”

“Something is coming uphill,” said Mother Wolf, twitching one ear. “Get ready.”

The bushes rustled a little in the thicket, and Father Wolf dropped with his haunches under him, ready for his leap. Then, if you had been watching, you would have seen the most wonderful thing in the world—the wolf checked in mid-spring. He made his bound before he saw what it was he was jumping at, and then he tried to stop himself. The result was that he shot up straight into the air for four or five feet, landing almost where he left ground.

“Man!” he snapped. “A man’s cub. Look!”

Directly in front of him, holding on by a low branch, stood a naked brown baby who could just walk—as soft and as dimpled a little atom as ever came to a wolf’s cave at night. He looked up into Father Wolf’s face, and laughed.

“Is that a man’s cub?” said Mother Wolf. “I have never seen one. Bring it here.”

A Wolf accustomed to moving his own cubs can, if necessary, mouth an egg without breaking it, and though Father Wolf’s jaws closed right on the child’s back not a tooth even scratched the skin as he laid it down among the cubs.

“How little! How naked, and—how bold!” said Mother Wolf softly. The baby was pushing his way between the cubs to get close to the warm hide. “Ahai! He is taking his meal with the others. And so this is a man’s cub. Now, was there ever a wolf that could boast of a man’s cub among her children?”

“I have heard now and again of such a thing, but never in our Pack or in my time,” said Father Wolf. “He is altogether without hair, and I could kill him with a touch of my foot. But see, he looks up and is not afraid.”

The moonlight was blocked out of the mouth of the cave, for Shere Khan’s great square head and shoulders were thrust into the entrance. Tabaqui, behind him, was squeaking: “My lord, my lord, it went in here!”

“Shere Khan does us great honor,” said Father Wolf, but his eyes were very angry. “What does Shere Khan need?”

“My quarry. A man’s cub went this way,” said Shere Khan. “Its parents have run off. Give it to me.”