Catherine Cooke, Pirate of the Malabar

A thrilling life 300 years ago

It came as a shock to 13 year old Catherine Cooke when John Harvey, chief of the British East India Company’s ‘factory’ in Carwar on the Malabar coast, asked her father Gerrard for her hand in marriage.

It happened on October 7, 1709.

Cooke, a poor gunner hired to work at Fort William in Calcutta, landed in Carwar on the ship Loyall Bliss with Catherine, her sister, brother and mother. The family was bound for Calcutta.

Harvey welcomed them.

In 1709 only about 200 European women lived in Hindustan, and thousands of Englishmen. Naturally, they could hardly find any European women to marry.

Some five Englishwomen lived in Carwar while in Bombay, soon to be Catherine’s home, they numbered about 16.

Harvey was overjoyed to see a very beautiful British girl just arrived from England.

Cooke could not refuse Harvey. Catherine, realizing her father’s compulsion, agreed to the marriage.

Harvey was quite rich. He had enriched himself by swindling the East India Company, as did many other officers of the era, by running a private business at the Company’s cost.

He offered Cooke ‘great settlements’ if Catherine would marry him.

The marriage was performed.

Shortly after, the Loyall Bliss set sail for Calcutta from the Carwar shores, carrying Cooke and his family. It reached Calcutta on October 22.

It is here that the story of an extraordinary woman begins.

What was life like then for the few European women in Hindustan?

The Pirates of Malabar, a book written by John Biddulph in 1907, tells us how Catherine Cooke fought against the East India Company for her property rights.

Her life appears like an action packed fiction. This rebellious woman, thrice widowed, led an extraordinary life in 18th century Hindustan.

Rolling in gold, John Harvey resigned from the East India Company and decided to settle in England. He came to Bombay with Cooke in April, 1711.

And her eventful life began.

Soon after marrying Harvey, Cooke realized she had committed a blunder. But nothing could now be done. She could free herself only when Harvey died.

It happened!

After living in Bombay for a short while, Cooke and Harvey returned to Carwar as some business was to be settled before setting sail permanently for England.

Suddenly, Harvey died. Catherine was a rich, young widow now.

A large number of legal duties befell her young shoulders, including the settlement of Harvey’s estate and his accounts with the Company.

Here we get an interesting insight into the functioning of the British East India Company: every Factor or head of a factory (trading post) was allowed to run their own businesses side by side. Often their accounts mixed up with those of the Company.

An overlap in trading accounts of the Company and the Factor happened to be very common. So the Company insisted on settling the dues of every Factor who resigned. Harvey did not settle this account.

The Company said that Harvey had swindled the corporate funds, which Catherine refuted. She now faced a serious situation. The Company turned harsh but she fought back. Mind you, all alone. Cooke was perhaps the only woman in contemporary Hindustan to fight against the powerful Company for her rights.

Suddenly, Thomas Chown, the newly appointed Factor at the Carwar Factory enters into her life. She marries him within just a few weeks of his arrival at Carwar. Catherine had known Chown since her Bombay days - his history is an interesting story.

On the stormy, rainy night of August 5, 1711, the ship Godolphin anchored near Bombay. Since that part of the sea was infested with dangerous pirates, the Godolphin did not dare approach Bombay harbour, its captain preferring to wait till daybreak.

But the storm turned violent, toppling the Godolphin at the foot of Malabar Hill. Chown and another officer William Gyfford somehow managed to swim to shore.

Interestingly, Gyfford would also be a part of Catherine’s life, but later on.

Meanwhile, the Company had sold Harvey’s Carwar estate to settle his dues. Catherine demanded a share as the estate belonged to her. But the Bombay Council of the Company refused, since it wanted to grab the whole sale proceeds of 13,146 rupees, 1 fanam and 12 budgerooks.

To Cooke’s arguments, the Bombay Council responded that as Harvey had made a will dated the 8th April, 1708 which was before his marriage with her, she could not get anything.

So it transpired that on November 3, 1712, Catherine Cooke and Thomas Chown left Carwar for Bombay to fight out her case, on board the ship Anne, which was also carrying valuable cargo.

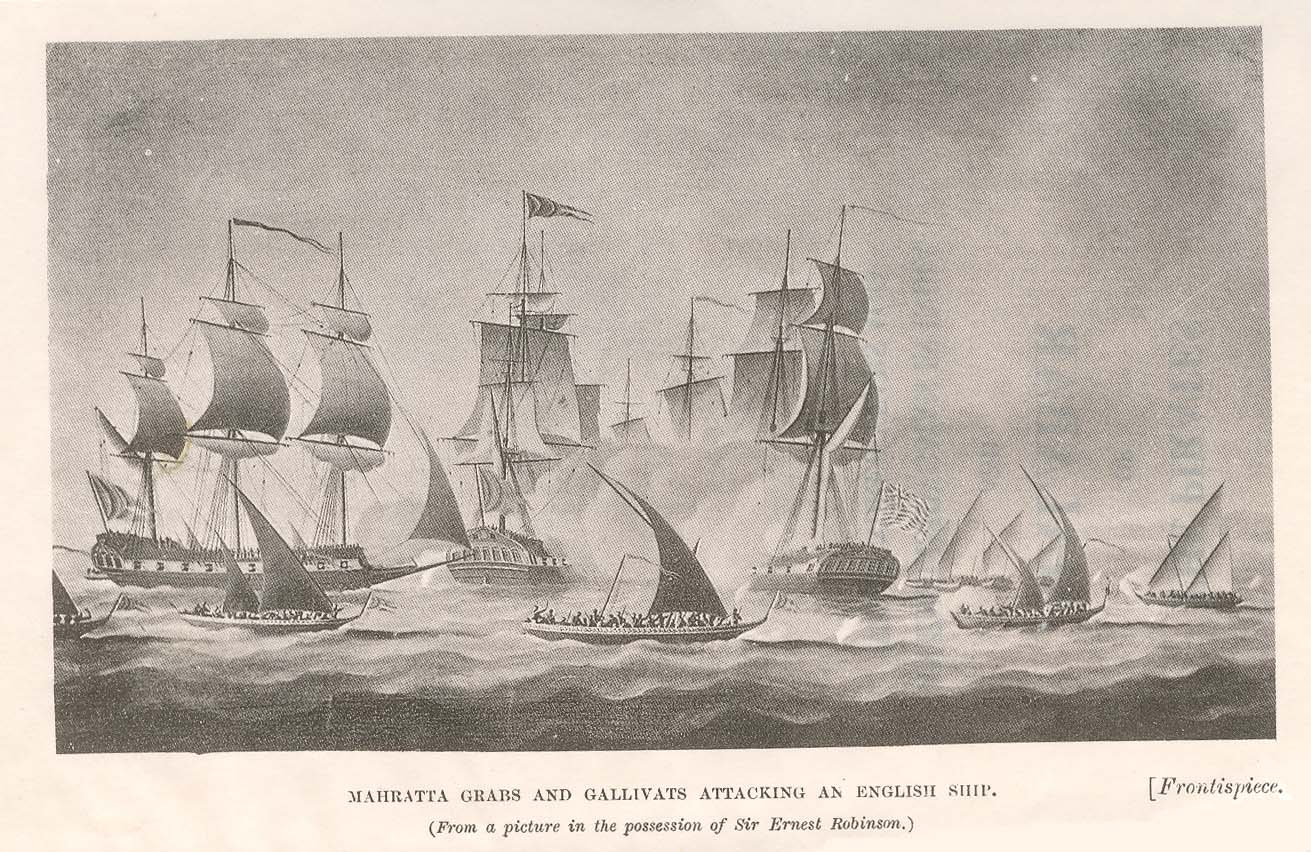

The Anne sailed through the Malabar Coast infested with pirates. The moment it came near Colaba, four pirate ships attacked. Soon a bloody fight began. Chown fought very bravely, but a cannonball severed his hand.

He died in the arms of his wife Catherine. She became a widow for the second time!

She was, at the time, expecting a child.

All on board the Anne were captured and were taken to a hideout near Old Woman’s Island - what is today known as Little Colaba. Catherine now was a prisoner of Kanhoji Angre, a name that filled with dread the hearts of sailors all along the Malabar.

Captured by one of the most dangerous pirates of the Malabar Coast, Cooke was regularly tortured for over a month. Finally, the captives were released on payment of 30,000 rupees on February 22, 1713.

Cooke and the other abductees reached Bombay. Shortly afterwards she was delivered of a baby boy. The Company gave her 1,000 rupees from her first husband’s estate for her personal expenses.

Soon, a third man enters Catherine’s life. It was William Gyfford, who swam to safety on Colaba shores when the ship Godolphin that also carried Chown tumbled at the Malabar Hills.

Cooke marries Gyfford. Soon, the Company pays her a further 7,492 rupees, being one-third of her first husband’s estate.

Meanwhile, Gyfford was promoted and sent to Anjengo, Travancore as Company Factor there.

Catherine was very happy! But only for a short while.

Anjengo was ruled by Rani Ashure who had allowed the British to start their Factory in 1688. The Dutch and French were also active there. The British asked the Rani’s permission to build a fort and total monopoly over the pepper trade which the Dutch and French strongly opposed.

Subsequently, the Rani ordered the British to stop the fortification. The Dutch and French wove their own conspiracies against the British and the Rani began to oppose the British presence in her kingdom. She decided to starve them out by disrupting their food supplies.

But the British adopted a defiant attitude leading the Rani to attack them. They repulsed the attacks, and continued with their businesses.

Rani Ashure had died in 1700 and chaos was let loose as there was no clearcut female claimant as ruler. After some time, a new Rani sat on the throne but she fell victim to court intrigues in which the British officers were also engaged.

A man named John Kyffin, thoroughly unscrupulous and very greedy, wove conspiracies against the fort in-charge Cowse who was removed from power. Kyffin indulged in court conspiracy against the royal family and sided with another corrupt man, Poola Venjamutta.

Consequently, Kyffin resigned and Gyfford succeeded him.

Anjengo was now the new address of Catherine Cooke.

But Gyfford too turned out to be dishonest. He antagonized the local people so much that they attacked the British fort at Anjengo. The Company sent Walter Brown from Bombay to settle the matter but he failed.

It is now 1721. Catherine has been in Hindustan for the last 12 years.

On the 11th April that year, Gyfford started for Attinga, four miles upriver. Suddenly, the local people attacked him and his men. The crowd killed many English soldiers. Some were cut into pieces. Gyfford was tortured to death.

Catherine became a widow again.

She set sail immediately for Fort St George, today’s Chennai. From here she left for Calcutta and joined her family there. At Fort St George she wrote to the Company demanding dues of her three late husbands, all of whom had allegedly duped the Company.

The Company, on the other hand, constantly demanded money that it claimed had been embezzled by her former husbands, alleging that she was in possession of it.

Meanwhile, a very daring naval commander Commodore Matthews came into her troubled life.

Matthews was an officer of the Royal Navy engaged in the suppression of piracy on the Malabar Coast, but rather than fighting pirates, he was engaged in private business, often dealing even with the buccaneers.

Matthews soon picked up enmity with the Company which found he was harming its interest and even diminishing its authority in the seas.

In September 1722, Matthews’ ship anchored at the Hooghly River in Calcutta. At the time the Company’s demands for the payment of funds embezzled by Cooke’s three late husbands were rising.

She sought Matthews’ protection, and he agreed.

Since he was at loggerheads with the Company, Cooke’s case impressed him greatly. Besides, he also liked the beautiful thrice widowed lady.

Suspecting that Cooke may escape with Matthews, the Company requested the naval commander not to take her from Calcutta till she had furnished security for the Company’s claim of 50,000 rupees.

But Matthews replied that he would take her to Bombay, where she would answer all allegations of the Company.

In January 1723 Cooke landed at Colaba with all her possessions. Matthews was by her side.

The Company was also ready to face her, with all documents showing the embezzlement of £9000 that her second husband had committed at Anjengo. In fact, her late husband had purchased cotton, cowries, pepper, and cloth with Company money but had kept them with him.

Now they were in Cooke’s possession. Thus she was liable to clear the dues.

She refused! And Matthews stood by her.

Apprehending that she might escape to London, the Company requested Matthews to ensure that Cooke did not leave Bombay till the dues were repaid.

Matthews defied the Company and helped Catherine on board the ship Lyon. She remained on board as landing at Colaba directly meant being caught by the Company.

Meanwhile, as the year 1723 drew to a close, Matthews decided to return to England with Cooke. For them to live together without being married created a massive scandal in Colaba, but neither of them were bothered by it.

The Lyon sailed from Malabar in defiance of the Company. The ship reached Portsmouth in July, 1724.

Hand in hand with Matthews, Cooke arrived in Portsmouth.

But here too, the Company chased her. It demanded the money. Its wrath now also directed at Matthews for shielding Cooke, the Company charged him with unlawful trading.

But the naval commander was not at all bothered.

Years passed. The Company could neither prosecute Matthews nor Cooke.

After this, we are completely lost. There is no official record about them, writes Biddulph.

Did she marry for a fourth time? If so the groom must have been Matthews. We, however, know not.