‘We are Eager to See What Limits There Are to Oppression’

Remembering Bhagat Singh

When Bhagwant Singh Mann was sworn in as the 17th Chief Minister of Punjab on Wednesday the 16 March in Khatkar Kalan – the ancestral village of revolutionary Bhagat Singh – in Banga, Nawanshahr, not many in that vast gathering realized an uncanny coincidence. It was also in the month of March, albeit 23 in 1931, that Bhagat Singh and his two comrades-in-arms Sukhdev and Rajguru were hanged at the Lahore Central Jail. The Chief Minister, however, energized the entire village when he ended his oath-taking ceremony with the ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ slogan that was Bhagat Singh’s war cry against the British.

Not many among generations X and Z would perhaps know about Bhagat Singh and his heroic battle against the erstwhile colonial British rulers. In some ways, he was a genius and a born leader. His father Krishan Singh was in Lahore Central Jail, and uncle Ajit Singh in Mandalay Jail when Bhagat Singh was born. He had grown up listening to the stories of the exploits of both his father and uncle. The Ghadar movement had also left a deep imprint on his impressionable mind. His hero then was Kartar Singh Sarabha, another revolutionary who was hanged in the first Lahore Conspiracy Case when he was barely 19. The massacre in Jallianwalla Bagh in Amritsar on April 13, 1919 too had left a deep scar on his mind, so much so that he drove all the way from Lahore to Amritsar just to kiss the ground that had been sanctified by the martyrs’ blood.

Bhagat Singh had initially studied at Lahore’s DAV School (incidentally, it was my alma mater too); he joined the National School in 1921 that had been set up by the trio of Lala Lajpat Rai, Bhai Parmanand and Sufi Amba Parshad. He was then just 14. It was there that he had also met his future comrades – Sukhdev, Bhagwati Charan Vohra and Yashpal.

At the National School, Prof. Jai Chandra Vidyalankar had become his mentor of sorts, and narrated the exploits of the revolutionaries in the erstwhile United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). All those revolutionary stories had so deeply inspired the young teenager that he then and there decided to dedicate his life to the cause of liberating Bharat Mata from the clutches of the British Imperialists.

While he was still at the National School, his father had arranged his marriage without even consulting him, leaving Bhagat Singh in an embarrassing position. However, he mustered enough courage to say NO. When his father became insistent saying that he had already arranged the match, the 14-year old Bhagat Singh wrote to his father,

“Respected Father, this is not the time for marriage. The country is calling me. I have taken oath to serve the country physically, mentally and monetarily (tan, man and dhan). Moreover, it is not a new thing for us. Our whole family is full of patriots. Two or three years after my birth in 1910, Uncle Swaran Singh had died in jail. Uncle Ajit Singh is living a life of exile in foreign countries. You have also suffered a lot in jails. I am only following in your footprints and thus dare to do this. You will kindly not tie me down in matrimony but give me your blessings so that I may succeed in my mission.”

When his father protested saying that he had already settled the marriage, Bhagat Singh again wrote to him,

“Respected Father, I am astonished to read the contents of your letter. When a staunch patriot and brave personality like you can be influenced by such trifles, what then will happen to the ordinary man? Yes, you are taking care for Dadi (my grandmother), but imagine in how much trouble is our Mother of 33 crores, the Bharat Mata. We still have to sacrifice everything for her sake.”

Before leaving the house, Bhagat Singh left a note for his father saying,

“Namaste, I dedicate my life to the lofty goal of service to the Motherland. Hence there is no attraction for me, for home and fulfillment of worldly desires. I hope you remember that on the occasion of my sacred thread ceremony Bapuji had declared that I was being donated to the service of the country. I am just fulfilling that pledge. I hope you would forgive me.”

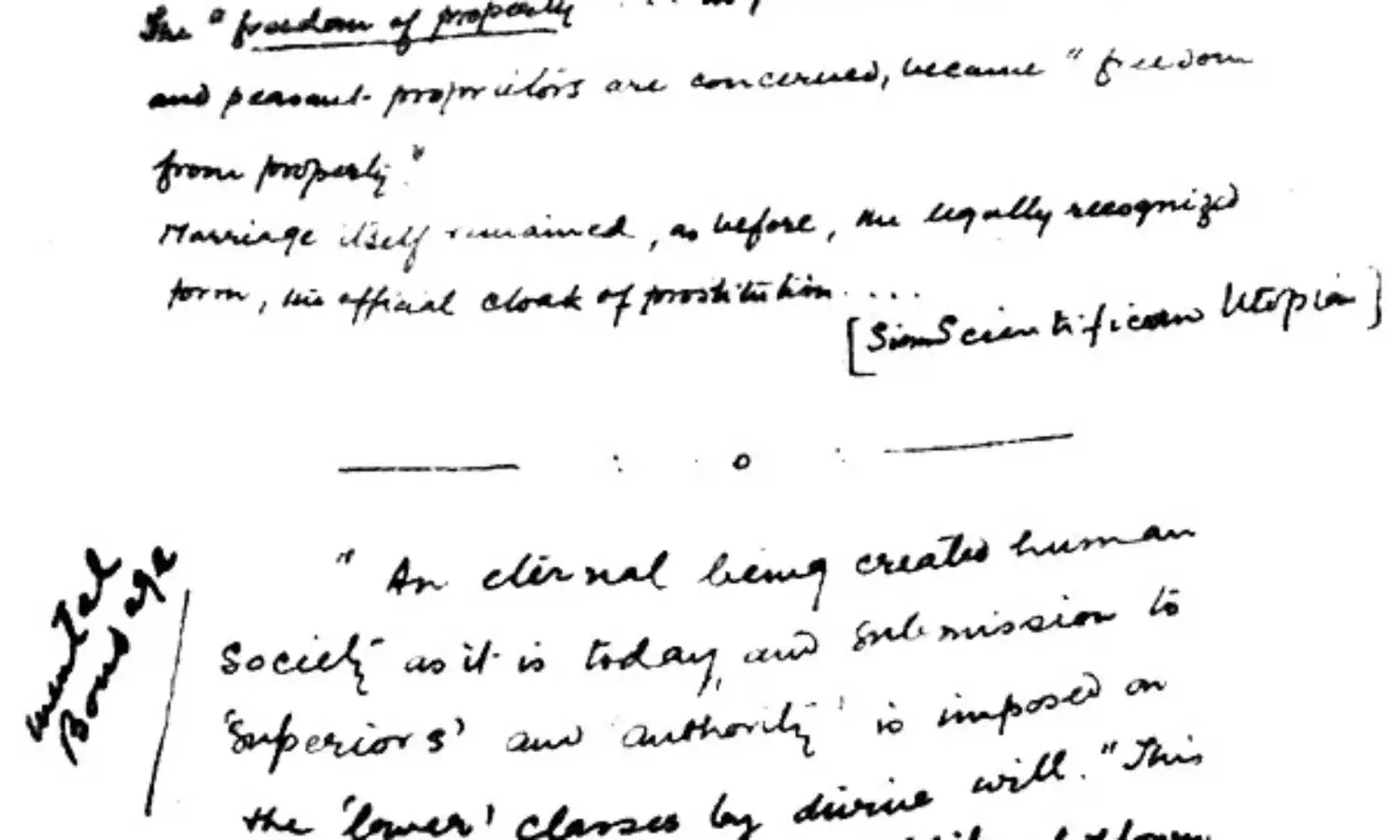

That Bhagat Singh was a great patriot and an extraordinary revolutionary was known to everyone. But not many of us knew that he was also an intellectual giant, an ardent Marxist thinker and an ideologue. A scholar par excellence, he wore his creativity on his shirt’s sleeves, as the pages of his amazing Diary that he wrote in Prison amply testify. Even at that young age, he was a voracious reader and had acquired “an in-depth understanding of Capitalism, Socialism, World Revolutionary Movements, and the history of the Bolshevik Revolution” and more besides.

Bhagat Singh was barely 16 in 1923. In a span of just seven years until 1930, he wrote furiously on a wide variety of subjects such as God, mysticism and religion, art, literature, culture, biographies of past and contemporary revolutionaries as also political leaders. Analyzing ‘the role of Religion and existence of God’ in his Essay ‘Why I am an Atheist’, Bhagat Singh had explained that for the primitive man ‘God became a useful myth’. For the distressed and the helpless, He served as ‘a father, mother, sister, brother, friend and helper’, all rolled into one. Thus, in a way, ‘God and religion came to the rescue of the man who was neither courageous nor had any scientific or rational understanding of things around him.’ With the progress of modern science and the growing struggle of the oppressed for their emancipation, the man stood on his own two feet without ‘the need of this artificial crutch’, thus ending the need for this imaginary Saviour.

Bomb in the Assembly

Two of Bhagat Singh’s most memorable revolutionary deeds were the murder of Assistant Superintendent of Police John Poyantz Saunders. It was unfortunately a case of mistaken identity. The original target was the Superintendent of Police J.A Scott who was believed to have struck the blows on Lala Lajpat Rai during a procession in Lahore on October 30, 1928 that proved fatal. The other was the ‘throwing of two bombs from the Visitors’ Gallery on April 8, 1929 in the Central Legislative Assembly’. The bombs had exploded near the benches occupied by the Official members causing minor injuries to a few.

It is not my purpose now to dwell on the details of these two incidents. Suffice it to say that meticulous preparations were made both in the murder of Saunders and the throwing of bombs in the Central Assembly. And but for the mistaken identity of Saunders, the two deeds were successfully carried out.

Bhagat Singh was very particular about the treatment that is meted out in jails to the political prisoners. In a letter published in The Tribune of July 14, 1929, Bhagat Singh and his comrade Batukeshwar Dutt had expressed their strong views:

“Sir, we, Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt, were sentenced to life transportation in the Assembly bomb case, Delhi, on the 19 May, 1929. As long as we were under-trial prisoners in the Delhi Jail we were accorded very good treatment and were given very good diet; but since our transfer from that jail to Mianwali and Lahore Central Jails respectively we are being treated as ordinary criminals. On the very first day we wrote an application to the higher authorities asking for better diet and a few other facilities and refused to take jail diet. Our demands were as follows:

. We, as political prisoners, should be given better diet and the standard of our dietary should at least be the same as that of European prisoners. It is not the sameness of diet that we demand but sameness in the standard of diet.

. We shall not be forced to do any hard or undignified labour at all.

. All books, other than those proscribed, along with writing materials should be allowed to us without any restriction.

. At least one standard daily paper should be supplied to every political prisoner.

. Political prisoners should have a special ward of their own in every jail, provided with all necessities as those of the Europeans and all the political prisoners in one jail must be kept together in that ward.

. Toilet necessities should be supplied to us, and

. Better clothing.

“We have explained the above demands that we made. They are most reasonable demands. The jail authorities told us one day that the higher authorities would comply with our demands. Apart from that they handle us very roughly while feeding us artificially, and Bhagat Singh was lying quite senseless on the 10th (sic) June, 1929, for about 15 minutes after forcible feeding, which we request to be stopped without further delay.”

“In addition we may be permitted to refer to the recommendations of the United Provinces Jail Committee by Pandit Jagat Narain and Khan Bahadur Hafiz Kidayat Hussain. They have recommended the political prisoners to be treated as better class prisoners.”

They added a Postscript: “By ‘political prisoners’ we mean those people who are convicted of offences against the State, for instance, people who were convicted in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, 1915-17, the Kakori Conspiracy Case and the sedition cases in Bengal.”

Bhagat Singh and his two comrades-in-arms had spent the ‘interim’ period of 166 days between the award of the death sentence and its execution on 23 March 1931 in cogitation, reflection and studying. In a letter dated 2nd February 1931 to the Young Political Workers, he had counselled them,

“Compromise is an essential weapon which has to be wielded every now and then as the struggle develops. But the thing that we must always keep before us is the idea of the Movement. We must always maintain a clear notion of the objective for the attainment of which we are fighting. Apparently, I have acted like a terrorist but I am not a terrorist. Let me announce with all the strength at my command that I am NOT a Terrorist, and was never one. I have been all along, in reality, a REVOLUTIONARY with definite ideals and ideology.”

He met his family for the last time on March 3. He told his younger brother Kultar in a letter,

“Dear Kultar, it made me very sad to see tears in your eyes today. There was a deep pain in your words. I could not bear to see your tears. My boy, pursue your studies with determination and look after your health. Be determined. What else …..(can I write?)….What couplets can I recite? Listen:

They are ever anxious to devise new forms of treachery,

We are eager to see what limits there are to oppression.

Why should we be angry with the world…and complain,

Ours is a just world (ideal), let us fight for it.

I am a guest only for a few moments, my companions,

I am the lamp that burns before the dawn and longs to be extinguished.

The breeze will spread the essence of my thoughts.

This self is but a fistful of dust, whether it lives or perishes.

Well, good bye.

Be happy, countrymen, I am off to travel.

Live courageously.

Namaste.

Your brother

BHAGAT SINGH

Then finally at 7.15 p.m. on Monday the March 23, 1931, shouting ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ the trio of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru embraced martyrdom. The following day March 24, the entire Nation mourned the execution of its bravehearts.

Some of the inputs on Bhagat Singh’s life were taken from A.G. Noorani’s Book ‘The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice’ published by Oxford University Press. My grateful thanks to him, and the publishers.

Raj Kanwar is 91-year old veteran journalist, writer and author. His latest books are DATELINE DEHRA DUN and its sequel.