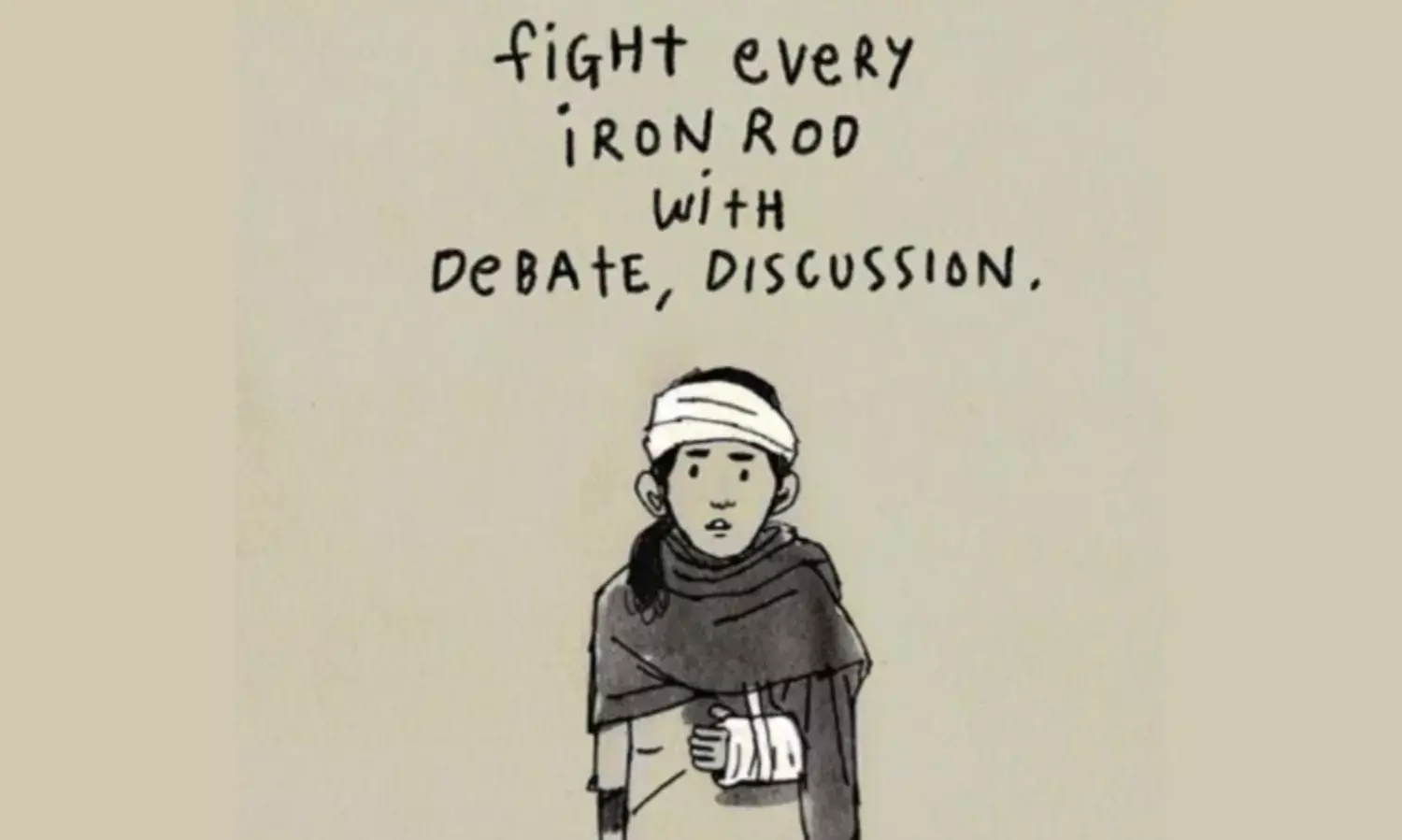

‘My Father Worries I Am Becoming a Desh Drohi’

Love in times of revolution

NEW DELHI: “Are you safe now, I saw you at the protest!” has become a typical chat-up line for matchers on dating apps in the wake of the protests against the CAA and much else taking place across the country.

Jaishree, a final-year history student, says “Most of my recent matches and I start off the conversation with politics and protests, asking each other about nation’s politics and protest plans.”

She believes that dating apps have become a crucial instrument - after many youngsters faced restrictions on social media apps - for discussing politics and mobilising people for forthcoming protests.

For Jaishree the scenario is unquestionably “Love in times of revolution”, but many of her age are experiencing a hostile atmosphere in their own peer and family circles.

Shatakshi Panwar, a journalism student whose relatives strongly support the BJP, says it’s difficult to openly debate her ideas with family elders, who believe politics has nothing to do with a young girl like Shatakshi who is only showing her disrespect towards elder wisdom.

“My father worries that I am becoming a ‘deshdrohi’ (traitor) when I speak against Modi or the BJP, and that it might turn out to be dangerous if I speak the same language outside on the streets. He literally threatened me not to go out for the protests,” she says.

Meanwhile, Manvi’s parents explicitly told her they would never bail her out if she was detained by the police. A student at Delhi University, she says she has saved up a good amount of money to keep herself out of legal traps, but hasn’t missed any anti-CAA protests yet.

Nor are parents the only ‘guardians’ around. Manasvi, another journalism student, says her father has never censored her freedom of speech. But her elder brother equates her dissent with a lack of education and awareness of history and the politics surrounding the issue.

“My brother himself looks for study materials to help me prepare for the Indian Institute of Mass Communication exam as he doesn’t at all want me to even apply to Jamia,” she tells The Citizen.

“He believes my communist and left-leaning teachers have already made me an Urban Naxalite, and if I land up in Jamia I would end up marrying a Muslim man!”

Psychotherapist Prachi Akhavi believes that “People are feeling unsafe in the very spaces where they are supposed to feel safe. The feeling that this person doesn’t share my views, so I don’t know how to be around them, is really stressing people out, making them feel distant and excluded in their own families.”

Tushar, a journalism intern, recalls, “I did a sensitive story in the wake of the attack on students in Jamia, so my parents got worried for my safety and didn’t let me take the byline for it, however much I wanted to.”

He says his father is a BJP supporter and they keep on having arguments which typically end with a ‘let’s agree to disagree’.

Like Tushar, Vanshika too has a father who shows her other sides of the story, countering her with facts rather than opinions, which she feels gives her a sense of validation and confidence.

Utkarsh, a student at Jamia who was arrested on the night of December 15, describes the fear and helplessness that followed in his family. He says his whole family supports his views and opinions, but there is nevertheless the constant reminder that he must not go to protests.

The sort of media channels the older generation tunes into plays a significant role in the formation of their ideologies, Shalini believes.

A student of convergent journalism, she says her father’s concern stems mostly from the natural parental instinct to keep their children safe from trouble.

Radhika Agarwaal, whose family are chartered accountants, recalls how she used to be so upfront in sharing her knowledge and opinions with them. However, recent debates and arguments with family members have completely changed her perspective, from anti-CAA to being “neutral”.

“When you are surrounded by an idea which the majority believe in, you automatically succumb to that belief, and your opinions end up becoming dissent to many,” she says.

All these cases share one aspect: the male elders asking, “If it doesn’t affect you directly, what is the need to be involved so much?” and the women choosing to remain silent about the argument, and playing the role of mediator instead, in case the situation escalates between father and child.

These tussles have further consequence. Akhavi says that “A lot of people who feel very strongly about how CAA-NRC will come as a cause of destruction, but are not able to contribute much on the ground, like by taking part in protests, feel very guilty and ashamed of not being a help to their comrades.”

As a reporter I find it curious that we’re expected to participate in voting but not political discussion or dissent.

Stuck in this situation, Shatakshi and others are left with no option but to take the battle online, actively voicing their opinions and spreading the word, which they aren’t able to do within their families.

“I feel mentally isolated,” says Shatakshi.

Others like Kim Kalyani, a student at Kalindi college, come across trolls by their knowns even on social media apps.

“I merely shared a post on which I got comments from my senior, asking me to leave the country and accusing me of being anti-national just because I don’t support the BJP.

“Over a trivial conversation she accused me of being uneducated and having no regard towards seniors. That’s nothing but her blindly following the herd,” says Kalyani.

“It’s high time,” Akhavi believes, “that regardless of ideological differences, people should create a healthy space for dialogues and discussions in families and social groups. That sense of solidarity and community is essential to prevent lasting psychological impacts on relationships.”

(Cover Photo: courtesy rajiv eipe)