What is Plaguing the Indian Health Sector?

Rent seeking has assumed gigantic proportions

Trying to get a convincing answer about the status of health services in India will elicit a variety of responses. Ask such questions and you will be swamped with statistics from government sources: trends in IMR, MMR, life expectancy, doctors per thousand population, and budget allocations, access to hospitals and other parameters. But statistics are just that: statistics.

80% doctors, 75% dispensaries and 60% hospitals are in urban areas, serving 28% of the population, according to a 2016 report. Only 37% of people in rural and suburban areas have access to medical care.

But does access get translated into medical help? Imagine starred hotels lined up in the cities: they are accessible, but can their services be availed by everyone?

The stark truth is that shorn of options, even the poor are constrained to approach private hospitals for the reason that the number of patients for every government doctor is humongous, forcing them to wait for several hours.

Loss of wages and doubts about the doctor being able to pay adequate attention lead patients to commercial practitioners. As multi-speciality government hospitals have been established only in major cities and towns, they are overwhelmed by patients from neighbouring villages and suburban areas where medical facilities are nonexistent or dismal.

More often than not, quacks walk in. Dependence on quacks is a common phenomenon and one will find quite a few in rural as well as poorer urban areas. Herein lies an important point of action.

The institution of corporate hospitals has further muddied the water, and needs to be discussed in detail. Suffice it to highlight the fine art they have made of fleecing any unfortunate individual who perforce lands in their net. In an era of astronomical “capitation fees” clearly those paying it are treating it as investment. Their major concern would be to get returns on investments, leading to jobs in or ownership of high-end corporate hospitals.

Invariably such hospitals try to get government lands, whose condition of free treatment to the indigent is routinely bypassed. Access is therefore a myth.

The stranglehold of pharmaceutical companies on the system, extending to medical devices like implants, is another area of concern. Rent seeking through unnecessary tests and avoidable procedures put great strain on family savings.

This is more rampant in the case of private hospitals and practitioners, but government doctors too are not immune to the practice. More on these another time.

To be meaningful, healthcare should conform to some basic norms. First level medical care should be reachable by everyone within the hour. This is the function of Primary and Subprimary Health Centres, but in most states it is an unsatisfactory position on the ground.

What’s worse is these centres are ill equipped, and doctors’ posts are either vacant or the incumbent is absent much of the time. As many a villager will tell you, he arrives a day before pay-day and disappears after 3-4 days.

Unfortunately such a situation prevails more in areas where the need is greater, like remote villages. The reasons cited are many and they need to be examined separately with some related issues.

The medical profession, which was once considered noble, is increasingly seen like any other business, with exceptions of course. The Hippocratic Oath intended to imbue a sense of propriety and responsibility in doctors to use their knowledge to treat and cure the patient efficiently and not take undue advantage of their ailment. But even the name may not ring a bell for many, since it is administered en masse these days with a loud “We do” from graduating doctors of medicine, and has become mere ritual today.

Health is all about the feeling of well being. In determining the effectiveness of health services a low incidence of ailments and a good life enjoyed by all people is as important as the quality of medical treatment. There is no merit in being a pill popping nonagenarian all your life, dependent on others in every way.

Other than ailments, medical intervention is needed for pre and postnatal care and during childbirth for safe delivery. While there has been some progress, there is no uniformity across states. Often services like transportation are lacking, negating the benefits of whatever infrastructure has been put in place.

Impoverishment, a major cause of disease, manifests itself through the denial of adequate nutrition, clean food and water, and hygienic living conditions. For these and to spread awareness the preventive role of medical practitioners becomes invaluable.

A vibrant health sector would be one that engenders well being in all individuals, and the confidence that any mishap or ailment will be promptly dealt with at an appropriate establishment, regardless of one’s social or economic status.

Medical care does not begin and end with a prescription. Much of the discomfort gets taken care of by doctor being “patient” enough to hear out the patient. The exceptions are fewer than one may like to believe, both in private as well as government sectors.

Not only will it help proper diagnosis, assurance and faith in medicine as well as the doctor, it will give recovery a better chance. Healthcare is womb to tomb affair that needs delicate handling by the person and the care giver, be it family, friends or doctors.

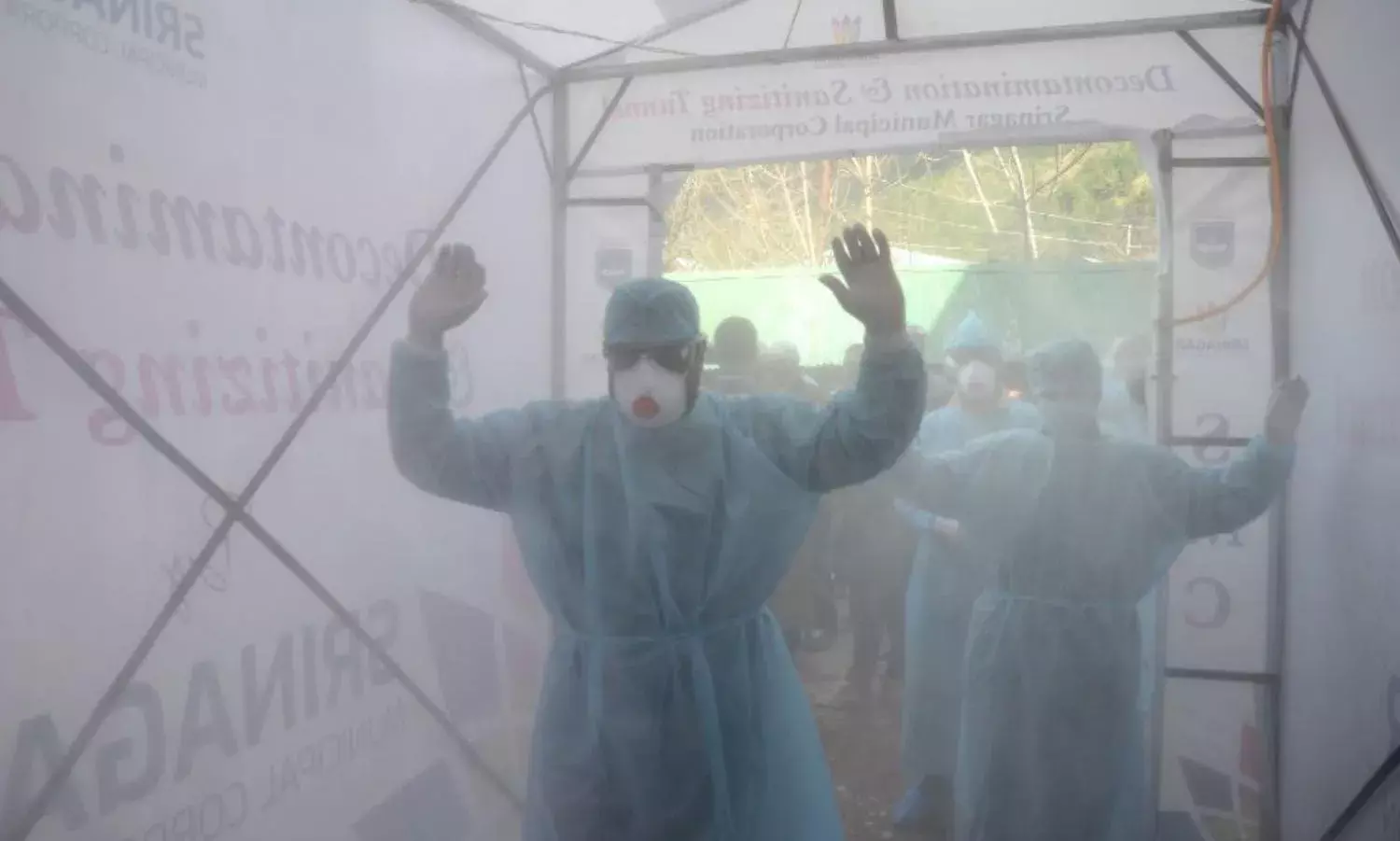

The chaos resulting from the COVID led crisis would have been handled more efficiently despite its unprecedented nature if the systems were in place. But rent seeking has assumed gigantic proportions, with the callous medical profession comfortably masked under the guise of their licence to play with human lives.

Arun Kumar is former Secretary, Government of India

Cover Photo: BASIT ZARGAR/The Citizen