How ‘Indian’ Is Swades?

Independence Day Special

Swades celebrates its 15th year of release. It is remarkable for presenting one of the most outstanding performances by Shahrukh Khan distanced completely from his mainstream screen image. It also stands out for its varied agendas cleverly interwoven into the script. The main subject of the film is to show the evolution of a global, NRI scientist who drinks only bottled water in India to his slow but steady metamorphosis into a genuinely “belonging” Indian. In short, according to Gowarikar, the film is about a man who discovers his roots.

Asutosh Gowarikar’s Swades demonstrates the tremendous diversity Bollywood represents within its cinema that reflects the widening parameters of Indianness on the one hand and its representation of globalization spanning a massive range of subjects, issues, ideas and social agendas on the other. The film was largely shot in Wai which is a remote village near Pune and famous for its Ganpati Festival. It is around 100 kms from Pune.

Swades is inspired by the story of Aravinda Pillalamarri and Ravi Kuchimanchi the NRI couple who returned to India and developed the pedal power generator to light remote, off-the-grid village schools. Rajni Bakshi’s Bapu Kuti narrated the true-life story of Aravinda and Ravi, and the Bilgaon project. Gowarikar is said to have been impressed with the work the couple had done as active volunteers of Association for India's Development (AID). Bilgaon is an adivasi village in the Narmada Valley which forms the backdrop of the Narmada Bachao movement. The idea of “lighting a village” became the trigger for the script of the film. The residents of Bilgaon village put in 2000 person days of shramdaan to make their village energy self-sufficient. The Bilgaon project is recognized as a model for replication by the Government of Maharashtra. Swades is also inspired by the Kannada movie Chigurida Kanasu, written by Shivaram Karanth, a Jnanpith Award winner.

Gowarikar had to make the film audience-friendly, entertaining and commercially viable. It was a big-budget film that demanded the Bollywood ingredients of romance, song-and-dance, drama and other things. It was difficult to bring about the balancing act between a development-centric story and mainstream Bollywood masala so that it did not become a dry documentary the audience would not have the taste for and the financiers and distributors would shy away from.

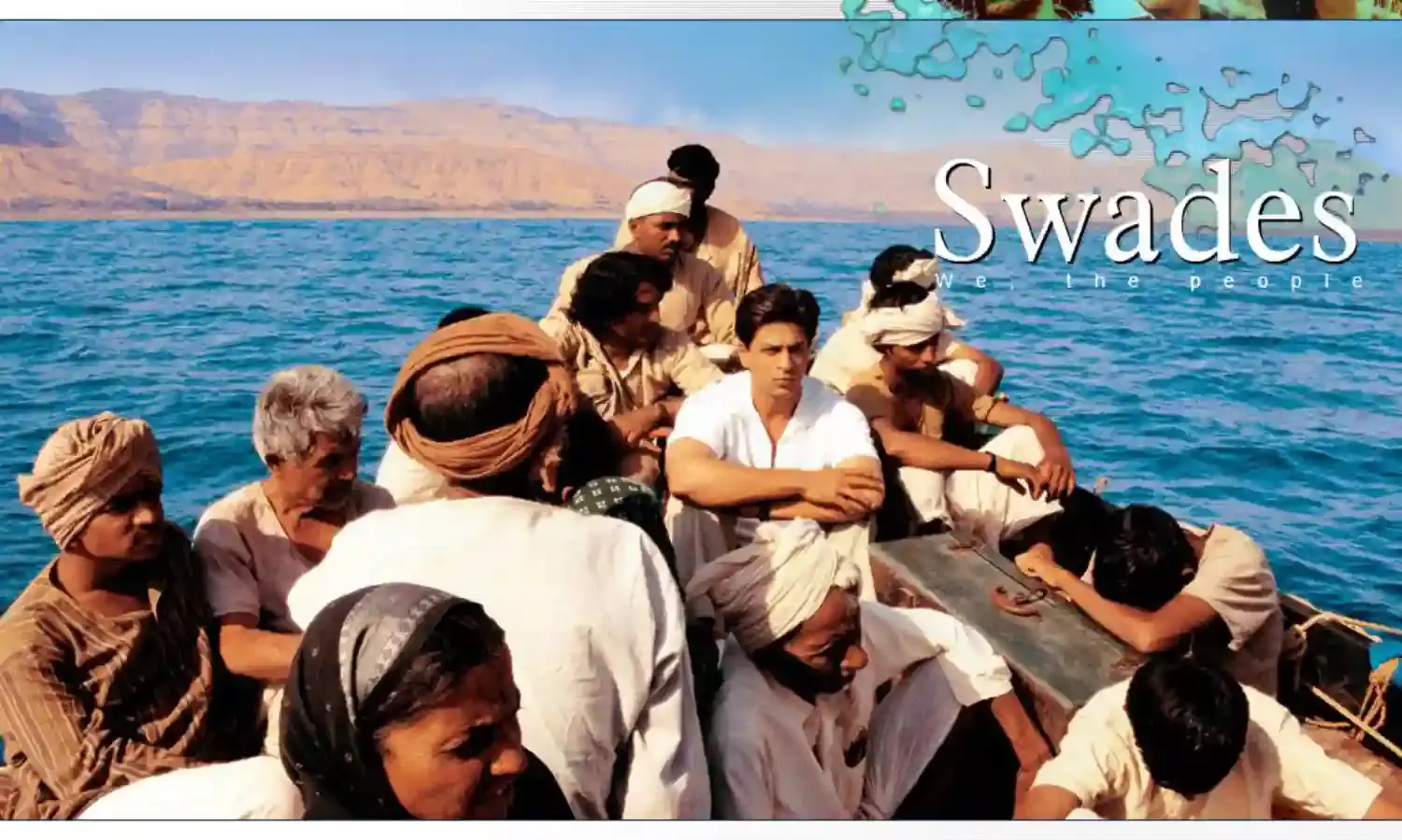

The script interweaves two to three very moving sub-plots to familiarize the scientist from NASA with the raw face of poverty. One is when he is travelling in a train and watches a little boy selling drinking water, quite dirty, to the passengers for a few naya paisa. The other is when at the end of this journey, he proceeds on a boat to the small village where a weaver-turned-farmer, who has leased a plot of land from Kaveri Amma and has not paid rent for many months to ask for the arrears on rent. In the boat, Mohan sits among a crowd of very poor villagers and is shocked to discover the real face of India. The skies behind him are clear and blue defining the contrast between the beauty of Nature and the ugliness of poverty existing together at the same time. There is a sense of “openness” in the film both in terms of the narrative and in terms of the cinematography.

When he reaches the village, there is more shock waiting for him. The weaver who was forced to take up farming, finds himself and his family cut out from both the weaving community and the farming community because for the weavers, he has walked out of them and for the farmers, he is an “outsider.” The entire family – his wife and kids, give away their dinner to their two sudden guests and Mohan cannot utter a word for fear of insulting their hospitality. After spending a sleepless night on a rope-bound khatia bitten by mosquitoes, Mohan, instead of asking this poor man about his dues, hands him a wad of notes from his pocket and comes away, a different and enlightened man. These scenes are dotted with an ominous and tragic silence where words are redundant.

Swades is a truly global Bollywood film that redefines the word “Indianness” in all its international glory. The film opens with a shot of the globe that zooms down into contemporary Washington DC, where its hero, Mohan Bhargava is a manager working on NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement project. Mohan Bhargava is a fully assimilated, literally globalized scientist who skillfully handles a press conference in high-tech, jargon-laden English.

Swades defines “Indianness” through collective action spurred by the hero functioning as a direct commentary on current conditions - (i) the rigid stronghold of the caste system in the fictional village of Charanpur, (ii) lack of proper educational infra-structure and schooling, (iii) the near-starvation levels a family is reduced to when the weaver is forced by economic circumstances to become a peasant, and (iv) the volatile nature of electrical energy in the village.

The film also brings across the material comforts NRI Mohan is used to. His fully equipped caravan is an example. He also drinks only bottled water – up to a dramatic point in the story but does not smoke in the presence of his adoptive mother Kaveriamma. The caravan radio plays old Hindi film songs working out a smooth blend of the ‘global’ and the ‘Indian’ that works towards a new definition of “Bollywood Indianness” in 2004. The song playing on the radio yun hi chala chal raahi spills over to its lip-syncing by the two travelers, Mohan and the street side wandering minstrel who asked for a lift symbolises Mohan’s willingness to return to his roots on the one hand and the journey into the unknown on the other.

Swades is enriched by the subtlety with which it brings in important issues. The caste-rigidity is brought about through a wonderful tribute to an old Bollywood entertainer Yaadon Ki Baraat. The curtain used for the screen neatly divides the upper castes and the lower castes by seating them on either side of the curtain in the open. But there is a sudden electricity failure and Mohan begins to sing along with the boys, the curtain comes off and the two groups naturally become one.

Popular cinema’s unifying potential is emphasized, and reaction shots of the crowd depict the responses of different audience segments to a given song sequence. The song that Mohan sings – yeh tara woh tara to keep the audience engaged when the electricity goes off is captured tellingly with the large shadow of Mohan falling across on the screen as he dances with gay abandon. The lyrics are philosophical and sing about how unity can make an ocean like the stars in the sky. Somewhere in the middle of the song, Mohan pulls the old school teacher to the telescope he has brought along to watch the twinkling stars in the dark sky. The postmaster-postman-wrestler pulls down the curtain that divides the crowds and the children from both groups merge and melt and join in the singing merrily along with Mohan. “ek tara nau tara sau tara” meaning – one star, nine stars, hundred stars, underlining the move towards solidarity between and among people. The cinematography shot in natural light with the stars shimmering in the dark sky is magical. This song fetched the National Award for Udit Narayan with the music by A.R.Rahman.

The best reflection of the changing nature of ‘Indianness’ through Bollywood cinema that is as ‘global’ as it is ‘Indian’ comes across in Swades in the way the ‘new Indian village’ is portrayed. Gayatri is an urban migrant who has chosen to educate the children of the village. Kaveriamma looks after home, hearth and Chiku, Gayatri’s brother. Mohan notices that Kaveri Amma looks after Chiku the way she looked after Mohan when he was a boy.

Navaran Dayal Shrivastava is postman, postmaster and wrestler, and like all bachelor wrestlers, a devotee of Lord Hanuman. Mela Ram is the Indian with the “Great American Dream” of opening a chain of dhabas in America and tries to curry favour with Mohan so that Mohan can become his ‘ticket’ to America. But when Mohan is ready to take him, he refuses, smiling. Dadaji is the beloved village elder and a former freedom fighter who lives just to see his village filled with the light the villagers brought in. The Panchayat head and his cronies are hooked on to traditional values and uphold casteist beliefs which Mohan tries to fight against in vain. But action succeeds where words fail. The characterizations in Swades are as much in a state of constant flux like Indianness is and globalization stands for.

The only drawback in the film is the scene where Gayatri waits for Mohan on the way to the airport to give him that box filled with a fistful of earth, some grass, grains of rice and so on which somehow, breaks the symphony of the entire film. It stands out like a scar on a beautiful face.

Any contemporary film with the “Bollywood” tag has some common features. These features spell out that almost all Bollywood films reflect both ‘globalization’ and ‘Indianness’ albeit in very distinct, individualised ways where the one cannot be compared with the other. Swades is also a journey film that marks the physical journey of Mohan Bhargava from the US to India to an insignificant and remote small town/village, and the inner journey of his transformation to travel from point A – the Indian-American nuclear scientist to point B – the Indian determined to bring electricity to a village that lives almost in the dark after sunset but where the elders are opposed to any change in breaking the caste barrier. The man who came to India for a short visit to fetch his favourite Kaveri Amma and take her back to the US with him, slowly begins to toy with the idea of settling down in his native country. But it is only after a short trip to the US to finally find out what he really wants and where he ultimately wants to settle down.