Supreme Court Picks Up the Gauntlet of Human Rights At a Crucial Juncture

ABHIK CHIMNI

The Supreme Court Judgement in Extra Judicial Executed Victim Families Association and Anr vs Union of India and Ors is significant for two reasons.

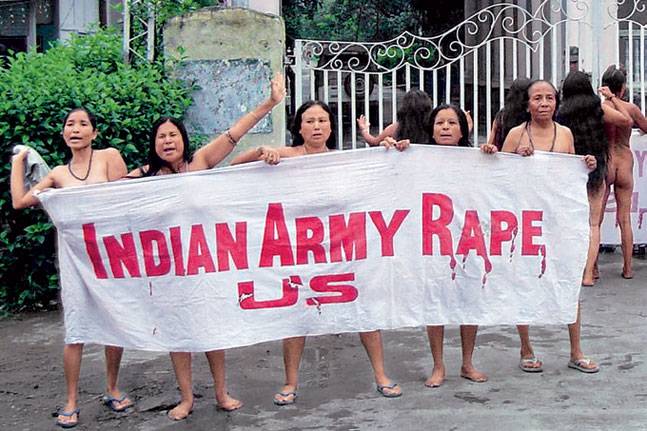

Firstly, it comes at a time when the expression ‘human rights’ is being undermined in popular discourse. The term is viewed as soft and apologist by voices who feel a tough and militaristic stance against the threat of insurgency and terrorism is being compromised by protecting such a right.

Secondly, the Court’s jurisdiction in a Public Interest Litigation has seen increasing criticisms by the State and civil society, the former for political reasons and the latter for reasons doctrinal.

In the context of the above Justice Madan B. Lokur’s and Justice U.U. Lalit’s public interest judgement ordering the filing of First Information Reports against members of the Manipur Police and the Central Reserve Police Force -- who have allegedly violated the law by using excessive force leading to death of civilians -- is welcome.

The above Writ Petition regarding extra judicial killings in Manipur was taken up in 2012, since then the Supreme Court has passed interim orders. The most important being on March 4, 2013 when the Court ordered the forming of a high powered Commission to consider the facts of six alleged extra judicial killings cited by the petitioners.

The Commission consisted of Mr Justice N. Santosh Hegde, former judge of the Supreme Court; Mr J.M. Lyngdoh, former Chief Election Commissioner; and Mr Ajay Kumar Singh, former Director General of Police. The Commission found all six incidents as not being genuine encounters and in every case the security forces seemed to have exceeded their right to self-defence.

Finally, in 2016, the Court listed for final hearing the issue on whether there should be an inquiry of any kind against members of the security forces for alleged cases of extra judicial killings. The Attorney General representing the Central Government opposed a judicial order allowing a criminal inquiry into the aforesaid incidents and those of similar nature. He argued that Manipur is in a “war like situation” and the provisions of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act 1958, specifically section 4(a) of the act, gives the armed forces the power to use force to the extent of causing the death of any person who is acting in contravention of any law or order, for the time of it being in force in the disturbed area.

The Court, on the above issues held firstly, that the Union of India has nowhere stated explicitly or implicitly that there is reason to believe that there is external aggression or an armed rebellion in Manipur.

Secondly, the Court held that there must be an animus to wage a war before a non-conventional war or war-like situation can be said to exist. Further, periodic but organised killings by militants and ambushes would not lead to a conclusion that there exists a war. If such a proposition is to be accepted it would reflect poorly on our Armed Forces and the Union of India. It would give an impression that they are unable to tackle a war-like situation for the last six decades.

Therefore, the Court cannot be expected to cast or even countenance any such aspersions on our Armed Forces or the Union of India. The Court held after much reasoning that within the Constitutional scheme the situation in Manipur is one of internal disturbance and not one of war.

Another important query the Court addressed is how one is to legally assess what is excessive or retaliatory force in relation to militants and terrorists. The Judges were of the view that there exists a clear difference between the use of force and the exercise of deadly force. One is an act of self-defence and the other one of retaliation. Relying on the constitution bench Judgement in Naga Peoples’ movement of human rights vs Union of India that upheld AFSPA, the Bench stated that as per the judgement, it was mandated that in view of any allegation against the misuse of power by the Armed Forces, there must be an inquiry.

The Court believed the rule of law mandates that wherever there is an allegation against the unlawful use of violence leading to civilian death, that there must be an investigation as per our criminal processes.

There is little doubt that our constitutional democracy’s emphasis on institutional checks and balances is crucial in helping building trust in establishments representing the power and majesty of the State.

The Attorney General also argued that militants and terrorists being fought in Manipur would fall under the term “enemy” under the Army Act, 1950 and therefore the limits of private defence and self-defence would have no application in this case. This is not an ordinary law and order situation.

The court concluded that if this argument is accepted it would imply that in Manipur any person carrying a weapon under prohibitory orders is an ipso-facto enemy of the State and therefore would justify the use of deadly force. In fact, the Court also brought to attention the Geneva conventions which states that even in war like situations minimum force should be used against the enemy. The judgement finally concluded that in face of an allegation it is only through a transparent investigation that one can know whether the deceased was an enemy or an unprovoked aggressor.

The Union of India also argued that the offences committed by members of the Armed Forces must be tried under the Army Act, 1950 through the process of court martial. Therefore, there was no requirement for those representing the army to be tried under the provisions of a criminal court under the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The Court did not agree with this proposition completely. Relying on Som Datt Datta vs Union of India, Balbir Singh vs State of Punjab and Army Headquarters vs CBI, the judgement held that there is no immunity of members of the Armed forces being tried by criminal courts. Though the Court on a reading of the various provisions of the Army Act 1950 and the CrPC did agree that prior to the stage of a criminal trial the sanction of the Central Government will be required.

On July 14, 2017 -- on receiving details of all the allegations of extrajudicial killings, the bench headed by Justice M.B. Lokur ordered that FIRs be lodged in all these cases. The FIRs to be lodged were to be based on incidents reported to NHRC and Judicial Inquiries. This was opposed by the Attorney General who said that many of the incidents are a result of pressure on the NHRC and other bodies by the local inhabitants of the state.

Further it was argued that the Court should not take this decision as many affected have not approached the court. However, the Court held that it would be in public interest that the rule of law is upheld and therefore a fair trial as per our criminal system must be conducted. Further the Court also asked that a special investigating team nominated by the CBI Director be set up, which would complete investigation and file the FIRs by December 31, 2017.

This judgement is not only one which protects the constitutional recognition of basic human rights but also adds to the credibility of the role of the Court as an anti-majoritarian voice; a role which is essential to our constitutional democracy.