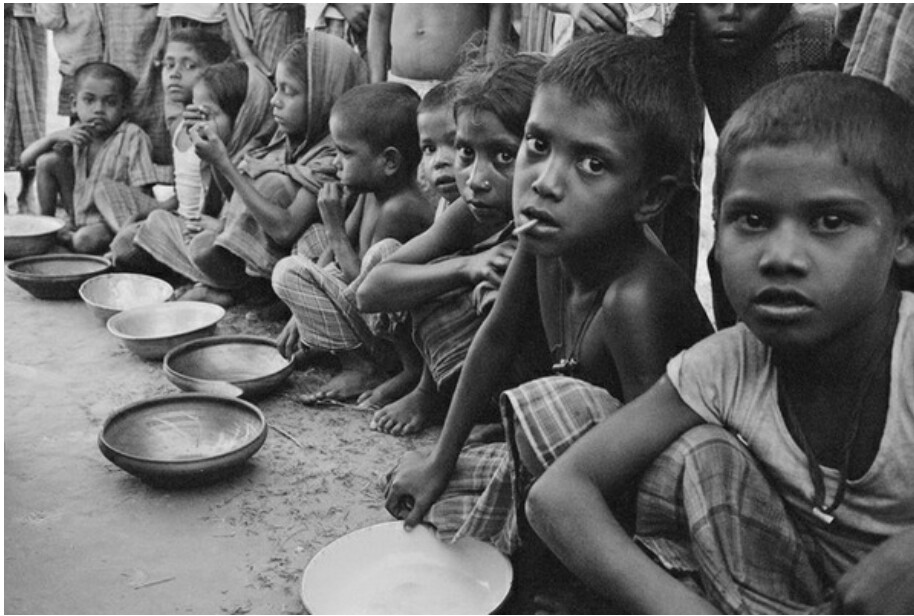

We Rank 100 in 119 Nations For Wasting Our Children But Yet We Don't Care, Shame!

NATASHA SINGH

NEW DELHI: India is wasting her children to a point where “serious” alarm bells should be ringing in the corridors of power that seem to be totally preoccupied with issues other than child and infant starvation and hunger.

This fall to 100 place (of 119) on the hunger index is registered for India at a time when the 2017 Global Hunger Index (GHI) shows long term progress in reducing hunger in the world. The decrease is 27 percent from the 2000 level. Of the 119 countries assessed by the GHI this year one falls in the alarming range, 44 in the serious range, and 24 in the moderate range. India is on the high end of the serious range in which undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting and child morality play a major part in the assessment.

As a result of the slipping Indian scores, as well as the not so amazing performance of the other countries in the neighbourhood, South Asia falls in the region with the most hunger, along with Africa south of the Sahara.

GHI itself has noted, “given that three-quarters of South Asia’s population resides in India, the situation in that country strongly influences South Asia’s regional score. At 31.4, India’s 2017 GHI score is at the high end of the serious category. According to 2015–2016 survey data, more than a fifth (21 percent) of children in India suffer from wasting. Only three other countries in this year’s GHI - Djibouti, Sri Lanka, and South Sudan - have data or estimates showing child wasting above 20 percent in the latest period (2012–2016).”

This comparison would have been seen as odious by India’s policy planners at one point in time, but has drawn little reaction from the ruling dispensation.

The child stunting rate is high at 38.4 percent, although less than the 61.9 per cent registered 25 years ago in 1992! GHI has basically confirmed what organisations in India have been saying, without any response from governments, that the timely introduction of complementary foods for young children declined from 52.7 percent to 42.7 per cent in the last 10 years. A major decline sought to be made up by the poorly implemented and now virtually withdraw mid day meal scheme for school going children, that is clearly not up to any recognisable mark.

So the areas of concern where India is faulting as identified by GHI are namely:

1. the timely introduction of complementary foods for young children (that is, the transition away from exclusive breastfeeding), which declined from 52.7 percent to 42.7 percent between 2006 and 2016;

2. the share of children between 6 and 23 months old who receive an adequate diet—a mere 9.6 percent for the country; and

3. household access to improved sanitation facilities—a likely factor in child health and nutrition—which stood at 48.4 percent as of 2016 (Menon et al. 2017).

http://www.globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2017/appendix-c.pdf

Since 2014 India has dropped 45 ranks on the scale, it is now behind North Korea and Bangladesh. The government that has done away with the mid day scheme as it was being run earlier, has now linked Aadhaar cards to the availability of mid day meals, particularly in states like Uttar Pradesh where it is being implemented with rigidity. Nearly 30 million children in India are sick, hungry and malnourished but they are not on any government’s map of policy and planning.

Children are the most vulnerable to disease, and given the poor nutrition in their formative years, their immune system becomes a ticking time bomb. Little has come by way of remedial action after the death of scores of children in a Gorakhpur hospital for want of oxygen; any number of incidents are recorded of children being killed by poisoned food served as mid day meals in schools; hundreds, indeed thousands, die of yearly diseases such as gastroenteritis, cholera and fevers.

GHI figures run the risk of become yet another ignored and rejected statistical warning in India’s corridors of power.