Depression Casts Cloak of Infertility Over Kashmir Valley

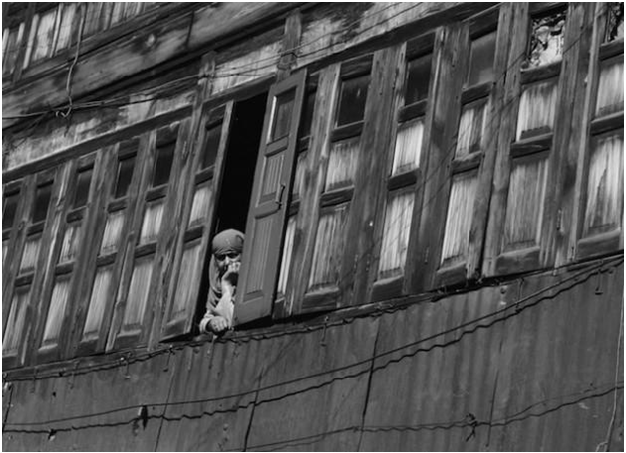

Of the 100 patients seen at Kashmir's psychiatric facilities each day, roughly 75 are women. Credit:

SRINAGAR (IPS): It was almost midnight when Mushtaq Margoob woke up to the incessant ringing of his phone. It was his patient, a young woman whom Margoob, a renowned Kashmiri psychiatrist and head of the department of psychiatry at the only psychiatric hospital in Kashmir, had been treating for depression for many years.

“See me now. I don’t have time till tomorrow,” the patient screamed down the phone. “I might have killed myself by then.”

The woman was educated, had a PhD in Bioscience and came from a rich family. After her marriage last year, the symptoms of her depression had begun to fade away, and she had started crawling back to a normal life.

But the day she made the hasty phone call to the doctor, she had learned something that shattered her life into fragments all over again.

“I have been diagnosed with Premature Ovarian Failure [POF],” she said to Margoob at his home. “If I cannot have any children, what should I live my life for?”

Although Margoob was able to pacify her with timely counseling and medication, the diagnosis and the constant reminder of being infertile have taken his patient back into deep depression.

“The mental stress due to ongoing conflict has taken a toll on the physical health of young women, especially their maternal health,” explains Margoob.

The conflict here, which dates back to the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan, has claimed some 60,000 lives as Indian armed forces, Pakistani troops and ordinary Kashmir citizens struggle to assert control over the bitterly contested region.

The “pro-freedom” uprising of 1989, launched by Kashmiris who resented the presence of Indian and Pakistani troops, morphed into a long-standing resistance movement that has left deep scars on Kashmiri society.

As a result, the area known as the Kashmir Valley, tucked in between towering mountain ranges in the northern Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, is witnessing an alarming increase in childlessness and infertility among local women.

Infertility is becoming increasingly common among young Kashmiri women, who are suffering from stress and trauma due to the long-standing conflict in the region. Credit: Shazia Yousuf/IPS

Physical and mental health experts cite conflict-related stress as the main cause of the health crisis among women, which has robbed thousands of their fertility.

The most recent Indian National Family Health Survey (NFHS) indicates that 61 percent of currently married Kashmiri women report one or more reproductive health problems.

This is significantly higher in comparison to the national average of 39 percent. The percentage of POF among infertile women below 40 years of age is also abnormally high – 20 to 50 percent – when compared to the nationwide rate of one to five percent.

“Stress causes structural changes in the brain and disturbs the secretion of various neurotransmitters. These changes lead to various physical ailments including thyroid malfunction, which in turn can cause infertility among women of childbearing age,” Margoob explains to IPS.

According to statistics available with the Government Psychiatric Diseases Hospital, 800,000 Kashmiris are suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and most of them are women. PTSD, like many other mental health disorders, directly affects women’s childbearing capacity.

In Kashmir, psychiatry OPDs are run at two hospitals – the Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (S.M.H.S) facility in Srinagar, and the Government Psychiatric Diseases hospital – six days a week. Of almost 100 patients seen at each OPD every day, 75 are females.

One of the many women who frequents these facilities is 20-year-old Mir Afreen, who grew up watching her mother battling mental illness. In 1996, when Afreen was only two, her mother, Shahzada Akhtar, received a message about the death of her cousin brother in cross-fire.

“I had met him only a day before. I couldn’t believe he had died. I tried to cry out his name but had lost my voice,” recalls Akhtar.

Akhtar never recovered from the sudden, devastating news, and soon developed PTSD.

In consequence, her daughter’s childhood quickly slipped into darkness. Afreen often saw her mother sedated, sleeping for days at a time, going without food, and crying for no apparent reason.

She was always taken along to psychiatric clinics, hospitals and faith healers where her mother searched for a cure for her condition. Happiness was far, far away from their home.

“I have gifted lifelong sadness to my daughter,” Akhtar tells IPS tearfully.

Her statement is not too far from the truth. For the last several years, Afreen has been complaining about chest pains and breathlessness. Akhtar first thought it was due to stress, or her daughter’s recent obesity.

But when Afreen developed facial hair and her monthly cycles became irregular, Akhtar took her to a gynecologist.

“The doctor uttered a long name which I couldn’t understand, so I asked her to explain the [condition] to me,” Akhtar says. “She told me if this is not treated, Afreen will never have children.”

Afreen was diagnosed with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). Unknown and almost non-existent before the conflict, the syndrome now affects 10 percent of Kashmiri females including teenagers.

A major endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age and one of the leading causes of infertility across the world, PCOS has emerged as another major cause of infertility among Kashmiri women in recent years.

Medical experts have identified stress as one of the main reasons for the emergence of PCOS in Kashmir. A study conducted by Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), the major tertiary healthcare facility in Kashmir, on 112 women with PCOS, found that 65 to 70 percent of them had psychiatric illnesses including PTSD, depression and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Akhtar feels helpless. Unlike other ailments, Afreen’s particular health issue is not up for discussion, not even with her own siblings. If the word spreads, she thinks, it will ruin her daughter’s marriage prospects and thus destroy her life.

“Even when I take her to the doctor, I make sure that no one sees us,” reveals Akhtar. “I first check the place and then let my daughter in.”

Afreen does the same. She has not revealed anything about her condition to her friends. When the girls talk about their grooms and life after marriage, she keeps mum. When it is the time for her medication, she secretly swallows the pills without water.

Nazir Ahmad Pala, an endocrinologist at SKIMS, says that more and more young females visit the endocrinology department for various disorders. A good number of disorders, he says, are born from depression.

Anxiety over the possibly loss of male breadwinners is prompting many women to choose education and employment over marriage. Credit: Shazia Yousuf/IPS

“In the past, the department received mostly older patients but now around 20 percent of our patients are school and college going girls with endocrine abnormalities. This trend is disturbing,” Pala tells IPS.

The young girls mostly complain of obesity and ovulatory disturbances that bring a temporary halt in their menstrual cycles.

The condition is called Central Hypogonadism and is common in depressed women, explains the doctor. Another equally frequent ailment is galactorrhea, a spontaneous secretion of milk from the mammary glands due to an abnormal increase of prolactin levels in the body caused by antidepressant intake.

“Unfortunately most of the [conditions], in one way or the other, lead to infertility. And the root cause of all these [conditions] is the stressful life that women have been living in the post-conflict era,” Pala asserts.

Experts here are sounding warnings about the catastrophic shape that women’s health in the Valley is taking. A study conducted at SKIMS on maternal health indicates that 15.7 percent of Kashmiri women of childbearing age will never have an offspring without clinical intervention.

Another conflict-related cause of infertility among Kashmiri women is late marriages. Over the war years, the marital age has risen from an average of 18-21 to 27-35 years. Because of economic insecurity and anxiety over the prospect of losing male breadwinners, women are choosing education and employment over marriage.

“Economic instability and insecurity is eating our society like termites,” says Margoob.

The doctor reveals that cut-throat competition in schools and colleges to earn a secure future has hugely disturbed the mental health of young girls as well.

Dissociative Disorders (DD), marked by disruptions or breakdowns in identity, memory or perception, are rapidly increasing in young school- and college-going girls, along with conditions like Panic Disorder, all of which interrupt the “smooth journey to motherhood”, Margoob says.

(*Patients’ names have been changed on request.)

(INTER PRESS SERVICE)