Jallianwala Bagh - 100 Years After

History from a retired general’s pen

The Year 2019 marks the Centenary of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, also known as the Amritsar Massacre that occurred on April 13, 1919.

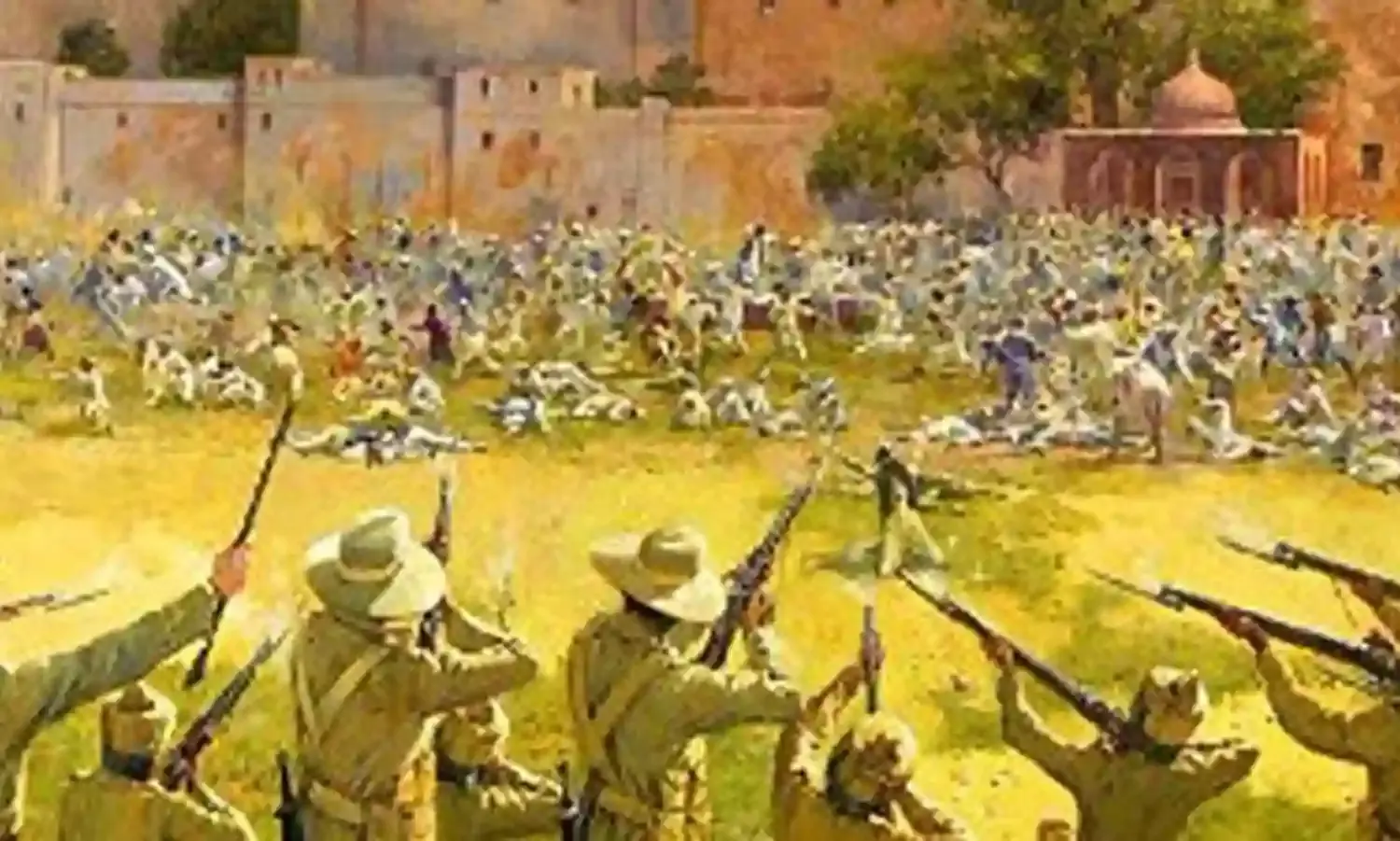

On this day, soldiers of the British Indian Army, on the orders of Colonel (temporary brigadier general) Reginald Dyer, massacred peaceful and unarmed celebrators, including women and children, on the occasion of the Punjabi New Year (Baisakhi). This massacre is remembered as one of the deadliest attacks on peaceful civilians in the world.

In the afternoon of that fateful day, Colonel Dyer, later called ‘the butcher of Amritsar’, on hearing that a meeting had assembled at Jallianwala Bagh, went with 90 soldiers to a raised bank near the entrance to the Bagh and ordered them to shoot at the crowd, without giving any warning. Dyer continued the firing for about ten minutes, until the ammunition supply was almost exhausted.

It was later stated that 1,650 bullets had been fired (derived by counting empty cartridge cases picked up by the troops). Official British Indian sources gave a figure of 379 identified dead, with approximately 1,200 wounded. The number estimated by the Indian National Congress was more than 1,500 injured, with approximately 1,000 dead.

This wanton massacre of innocents had shaken the whole of India and was the beginning of the end of the British Colonial Empire in India.

It left a permanent scar on India-British relations and was the prelude to Mahatma Gandhi’s full commitment to the cause of Indian Nationalism and independence from Britain.

During World War I (1914-18), when Britain and its allies were on the verge of losing the war, it was the Indian Army and forces of Indian Princely States, which had turned the tide against the British. About 1.3 million Indian soldiers and workers served in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, while both the Indian government and the princes contributed large supplies of food, money, and ammunition. It was generally believed that on account of the overwhelming support to the war effort, India would be given more political autonomy when the War ended.

During the War, the British government in India had enacted a series of repressive emergency powers that were intended to combat subversive activities. However, people of India had expected that these measures would be eased when the War ended. The Montagu-Chelmsford Report, presented to the British Parliament in 1918, did recommend limited local self-government in India. However, the Colonial Government of India, through the Rowlatt Act promulgated in early 1919, extended the repressive wartime measures.

After World War I, the high number of dead and wounded; inflation; heavy taxation; and other economic problems greatly affected the people of India. The worsening civil unrest throughout India, especially amongst the Bombay millworkers, led to the Rowlatt Act being promulgated. The Act gave the Viceroy's government great powers, which included censoring the press; detaining political activists without trial; and arrest without warrant of any individual suspected of treason. This Act sparked a wave of anger within India.

Mahatma Gandhi's call for protest against the Rowlatt Act, got the expected response of furious unrest and protests, especially against the restrictions on a number of civil liberties, including freedom of assembly and banning gatherings of more than four people.

The law and order situation, especially in Punjab deteriorated quickly. Many rail, telegraph and communication systems were disrupted, along with processions and protests. A huge crowd of 20,000 marched through Lahore. By April 13, the British government had decided to place most of Punjab under martial law.

April 13 was also the date for the Spring Festival of Baisakhi that was celebrated with great enthusiasm. That year too many persons from the villages surrounding Amritsar were visiting the city to pray at the Golden Temple and celebrate the festival.

Events Leading to the Massacre

On April 10, 1919, a protest was held at the residence of the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar. The demonstration was held to demand the release of two popular leaders of the Indian Independence Movement, Satya Paul and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had been earlier arrested on account of their protests. The crowd was shot at by British troops, which resulted in more violence. Later in the day, several banks and other government buildings, including the Town Hall and the railway station were attacked and set on fire. The violence continued to increase and resulted in the deaths of some Europeans, including government employees and civilians.

For the next two days, the city of Amritsar was quiet, but violence continued in other parts of Punjab.

On 13 April 1919, Colonel (temporary Brigadier General) Dyer reached Amritsar from Jalandhar Cantonment and virtually occupied the town, as the civil administration under Miles Irving, the Deputy Commissioner, had come to a standstill. On the same day, convinced of a major insurrection in the offing, Dyer banned all meetings. However, this notice was not widely disseminated.

The Jallianwala Bagh

The Jallianwala Bagh, located close to the Golden Temple in Amritsar, derives its name from that of the family of the owner of this piece of land, Sardar Himmat Singh, a noble in the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), who originally came from the village of Jalla, now in Fatehgarh Sahib District of Punjab.

The Jallianwalla Bagh in 1919, months after the massacre.

At that time, it was a garden or a garden house. In 1919, the site was an uneven and unoccupied space, an irregular quadrangle, indifferently walled, approximately 225 x 180 meters. It was surrounded on all sides by houses and buildings and had few narrow entrances, most of which were kept locked. It had only one entry/exit leading from a narrow lane.

On April 13 1919, thousands of people had gathered in the Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate the Baisakhi festival, which was also the Sikh New Year. For more than two hundred years, this festival had drawn thousands from all over India. In 1919 too, people had travelled for days to get to Amritsar. The bulk of the crowd consisted of families who had come to the city from surrounding villages to celebrate the Baisakhi Festival.

There were also a small number of protestors who were defying the ban on public meetings and had come to pass a protest resolution to condemn the arrest and deportation of two national leaders, Satya Pal and Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew and the repressive Rowlatt Act that provided for stricter control of the press; arrests without warrant; and indefinite detention without trial.

It needs to be emphasized that the entire assembly was peaceful and unarmed.

Colonel Dyer and about 90 soldiers arrived at about 04:30 PM at the Bagh and sealed off the only exit. Without giving any warning, the troops opened fire indiscriminately on the crowd. Everyone ran helter-skelter, but there was no escape. Unable to escape, people tried to climb the walls of the park but failed. Many jumped in the only well inside the Bagh to save themselves from the British bullets. It was later reported that 120 bodies were taken out from the well. Many others were trampled to death in that confined space.

The firing lasted for about 10 minutes and ceased only when the soldier’s ammunition was nearly exhausted. The troops immediately withdrew from the place after firing, leaving behind the uncared dead and wounded.

It is not certain how many died in the bloodbath, but, according to the official report, an estimated 379 people were killed, and about 1,200 more were injured. The Indian National Congress, however, estimated that more than 1,500 were injured, with approximately 1,000 killed in cold blood.

It was a most dastardly and cowardly act that can be classified as the lowest point of the British Rule in India. The incident fueled anger among people, leading to the Non-cooperation Movement of 1920-22.

The Aftermath

The British Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, Sir Michael O’Dwyer initially commended the action of Colonel Dyer and recommended martial law to be imposed in Amritsar and other areas; this was allowed by the then Viceroy.

The shooting, followed by the proclamation of martial law, public floggings and other humiliations enraged all Punjabis. Indian outrage grew as news of the shooting and subsequent British actions spread throughout the subcontinent. People were talking of nothing else and newspapers were writing about nothing else! Jinnah had made a strong anti-British speech at a public meeting. Gandhi had returned to the Government the medal that it had conferred on him for his services during the War. The Bengali poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore renounced the knighthood that he had received in 1915. Gandhi soon began organizing his first large-scale and sustained nonviolent protest (Satyagraha) campaign, and the non-cooperation movement (1920–22), which thrust him to prominence in the Indian Freedom Struggle. He had declared that “cooperation in any form or shape with this satanic government is sinful”.

The government of India ordered an investigation of the incident (the Hunter Commission), which in 1920 censured Dyer for his actions and ordered him to resign from the military. Reactions in Britain to the massacre were mixed, however. Many condemned Dyer’s actions—including Sir Winston Churchill, then Secretary of War, in a speech in the House of Commons in 1920—but the House of Lords praised Dyer and gave him a sword inscribed with the motto “Saviour of the Punjab.” In addition, a large fund was raised by Dyer’s sympathizers and presented to him. In July 1920, Dyer was censured and forced to retire.

The Denouement

Udham Singh (26 December 1899 – 31 July 1940), a Punjabi revolutionary assassinated Michael O’ Dwyer, former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab on 13 March 1940 in Caxton Hall in London.

Udham Singh (second from left) is being taken from 10 Caxton Hall after the assassination of Michael O’Dwyer.

The assassination was in revenge for the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre in Amritsar in 1919. He was subsequently tried and convicted of murder and hanged in July 1940. He is well known as Shaheed-i-Azam Sardar Udham Singh. A district (Udham Singh Nagar) of Uttarakhand was named after him in October 1995.

In Udham Singh's diaries for 1939 and 1940, he occasionally mis-spelt O'Dwyer's surname as "O'Dyer", leaving a possibility he may have confused O'Dwyer with the infamous Brig General Dyer.

On the 100th anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, all Indians need to pay their tributes to those wantonly killed by an egoist colonial British Army Officer, without any compassion for the dignity of human beings.

The indomitable spirit of all Indians who had fought the British Colonial Raj and ultimately gained Independence for us needs to be remembered and honoured, for they had sacrificed their lives for our freedom.

(The writer is a former Vice Chief of Army Staff).