The Political Lie

Political lies can, and do, cause widespread damage.

About 30 per cent children begin lying around the age of two. By age four, most have learnt to. Psychologists consider this a sign of cognitive progress. The average person lies about 1.65 times a day, which sounds like a lie itself. And while they range from the white to the obfuscatory, exaggerations to omissions, fabrications to denials, all wilful lies serve one central purpose. To mislead. In a bid to either promote or shield oneself. Or a person/ cause/ narrative one holds dear.

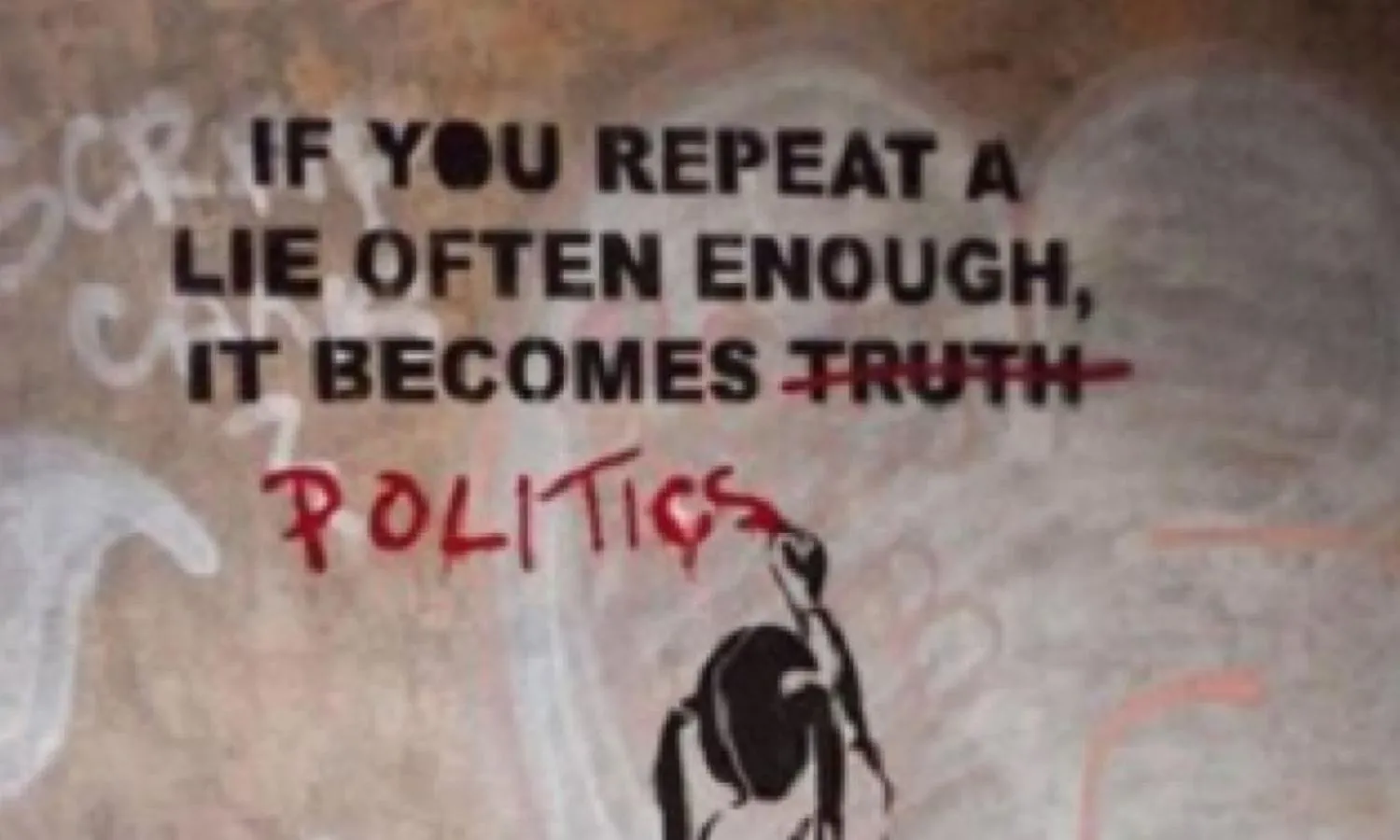

So, if lying is natural, common, and fundamentally single-purpose, why single out politicians for scrutiny? One view is that political leaders should be held to a higher standard since they claim or aspire to represent and lead us. If this comes across as hopelessly idealistic in the backdrop of both history and present, let us turn to the practical reason why political lies should concern us.

Political lies can, and do, cause widespread damage. The sufferers are us, our families, our communities, the nation, indeed the world. Of course, disturbing as the notion may be, a certain amount of spin and identity-based appealing is expected in electoral politics. I speak hence with reference to the more exceptionable strains of political lies: (a) inflated claims of performance; (b) concealment of incompetence and corruption; and, (c) twisting and conjuring of statements and events, historical and contemporary, to boost divisive agendas.

Here is how and why political lies hurt, large-scale and deep.

One: Since political success depends on popular support, the political lie is calculated to deceive and impress large numbers of people. Which, together with the (alas, common) absence of dazzling achievements to showcase or daringly meaningful ideas for change, explains its high decibel delivery and accent on emotional manipulation and othering.

Two: The three most common types of political lies mentioned above are rooted in poor prioritization and swindles of our (tax) money and threaten a meaner world for us and our children.

Three: It is in the nature of lies to snowball and when political lies snowball, they spawn conspiracies of silence involving political rivals, various branches of government, big business, and the media. Public institutions especially lose a bit of sheen and spine with every instance of complicity. The resultant institutional crumble means that they become progressively less equipped to address their lofty, citizen-serving mandates. In the end, we will be left with institutions that serve not the public cause but leaders’.

The political lie then is not just an abstract moral issue (not that there is anything wrong in dwelling on moral issues- they could well be the keystone for change) but one which propels people and nations towards palpable impoverishments, social, economic, and institutional.

Before moving to the lie-busting tools we have and how they could be better deployed, a bit about lies that emanate from those in government. Such lies are extra-troubling because of the implicit trust that governments enjoy and the powerful levers governments can deploy to magnify or conceal their deceptions.

Importantly, while citizens can be penalized for lying to the government, there are few penalties for governments who lie to citizens. Even if the case for complete equivalence on this aspect of the elected representative-citizen relationship is arguable, it is certainly reasonable to expect a degree of reciprocity.

Lying, as mentioned earlier, is motivated by a desire to mislead. It becomes a habit, at least an increasingly resorted to option, when individuals think they won’t be caught. Or think they can get away lightly even if they are caught.

To check political lying then, we need arrangements to unmask lies and dissuade their purveyors. The current arrangements we have are struggling.

Ruling parties, irrespective of political persuasion, have managed to get around parliamentary oversight mechanisms, institutional checks, and judicial processes. The Right to Information stands diluted, its disclosure requirements scoped down, its anchor institutions systematically weakened. A large section of the media has a credibility problem partly of its own making, independent fact-checkers stand accused of bias, and new, shady media outlets and fact-checkers are confusing the picture.

Catching a lie is clearly getting tougher. The consequences of being caught don’t appear heavy either. Investigations and courts can be slow and unpredictable. Political parties aren’t exactly itching to punish proven liars in their ranks, may even appreciate their value as campaigners and spokespersons.

Most important, lying does not appear to induce the one thing politicians fear: popular upset. Perhaps truthfulness isn’t a differentiating factor among candidates who line up for votes, but there is still something to be said about people’s enthusiastic circulation of false-marked social media posts and their blind acceptance of whatever their preferred party says.

In terms of the way forward, action is required at several ends. Self-regulation among politicians and political parties would help a great deal, but it is unwise to pin hope on that. At the moment, there is no compelling reason for them to make amends.

Mediapersons, fact-checkers, activists, and researchers with an interest in facts and fact-laced narratives must persist. On days when viral falsehoods deflate them, they must remind themselves of how much worse things could be if there was none left to spotlight lies.

Institutional assertions can do much: put facts in the public domain, starve speculation, withstand pressures to cover up embarrassing truths and further toxic agendas, ensure that cases of fraud on the exchequer and hate speech are pursued to logical conclusions. A lot of our present worries are on account of institutions flailing in these.

Blight has set in, and revitalization won’t happen overnight. But there are silver linings.

The constitutionally envisaged distribution of powers between various branches of government along with checks and balances continues to provide public institutions the space to do the right thing. Issues of institutional independence and capacity do exist. Fortunately, there are enough Committee and Commission reports to dig out and address them. Encouragingly, as a series of Election Commissioners showed us not very long ago and several judges, policemen, and civil servants have demonstrated since, a handful of upright individuals can leverage these and usher more change than looks possible prima facie.

Finally, citizens must examine their own roles in incentivizing political lying. A mix of confirmation bias and ends-justify-means logic means that we are not making the effort to question even blindingly obvious lies and energetically, unapologetically consuming and disseminating falsehoods. Psychologists believe interactions with the Other side is the key to overcoming bias. That is a worthy pursuit, but requires stage-setting and time.

Meanwhile, we could launch our own personal fight backs. How about refusing to share anything that carries a fake news tag, apologizing every time something we shared is found untrue, reading up rival parties’ posts on a subject before offering our own hot takes, and subscribing to a media outlet we currently scorn? If this seems too much, begin with any two. Add to the arsenal as you go along. It is going to be a long haul.