There Is A Storm Brewing Across the Himalayas

Ladakh- the way forward

China’s moves in eastern Ladakh point to its penchant for long term planning, more so in this vital region.

The road linking Tibet with Xinjiang runs through Aksai Chin for 167 kilometres, while the recently built road by India connecting Leh with Daulet Begh Oldi can facilitate a quick buildup of forces in this part of Ladakh, giving India the ability to capture Aksai Chin which has been under Chinese control since the 1950s.

Such an act by India threatens Beijing’s links with the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and the Tibet Autonomous Region. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) initially are linked to this highway as well.

Such an apprehension was perhaps heightened when Union Home Minister Amit Shah told Parliament last August that “whenever I say state of Jammu & Kashmir in the House, then both PoK and Aksai Chin are part of it”.

It would be reasonable to assume that China’s moves in the Pangong Lake, Galwan Valley, Hot Springs and Depsang Plain are a consequence of this apprehension: that India may at some future date make an attempt to capture Aksai Chin.

Beijing’s moves give the PLA the ability to intercept the road from Leh to the IAF airbase at Daulat Beg Oldi. Therefore, the ongoing standoff in this region may continue for quite sometime.

There is also the possibility that China, at some future date, may take the Karakoram Pass, for the BRI and CPEC to run across it and beyond through the Shaksgam Valley. This will substantially shorten the distances for the CPEC and BRI.

What is likely to happen here onwards in Ladakh is similar to what happened at Dokhan, where China has constructed a road almost up to where their troops had come up. China has also put up permanent structures and continues to occupy this Bhutanese territory. At best, in Ladakh it may follow the policy of two steps forward and one step back. Or we may not have adequately deciphered China’s longer term plans for the Ladakh region.

When Parliament designated Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh centrally administered territories, and Chinese troops moved into the area, there arose the need to relook at the infrastructure required for better connectivity with this region.

The main connection with Ladakh, instead of through the Kashmir Valley, should now be through Himachal Pradesh. To that end the existing road via Kullu-Manali needs to be made double-laned. Extension of a railway line from Joginder Nagar to Leh should be expedited, and the railway line from Shimla extended to Kelong, to join the one from Joginder Nagar. The existing Kalka–Shimla road should also be extended, from Lasar to Demchowk and then on to Upshi.

With reports of a new set of roads being built in China just across the border from Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, there is perhaps a compelling requirement to rework the military infrastructure, particularly along the border with Tibet: from Ladakh to the Lipulekh Pass.

A separate command for this area needs to be created and named the Northern Command. It would require a minimum of two corps (one presently in Ladakh, the 14 Corps, and a second from the present Northern Command) with adequate assets as command reserve.

This Command should have the ability to, when required, mount an offensive to intercept the road from Lhasa to Xinjiang at selected places. China is rather sensitive to any disruption of this road, as it is heavily invested in BRI and CPEC. India’s military potential to interdict this road will be enough of a deterrent for China to avoid creating any mischief in Ladakh.

This Command could in due course be reorganised as the Northern Theatre Command, and the present Northern Command could be re-designated the North Western Command with two corps, i.e. 15 and 16 Corps. The third corps with the present Northern Command could be given to this new Command, as and when it is raised.

Given the ongoing problems China is having with the US, its largest trading partner, as also some European countries, it is worth remembering that India is China’s seventh-largest trade partner accounting for 3% of Chinese exports, about the same as Germany.

By shrinking this market for Chinese exports India can perhaps put pressure on China, which accounts for 5–6% of Indian exports. India should limit imports from China and restrict entry to Chinese companies seeking contracts and business expansion here.

Taking some of these steps, and creating the potential to interdict the road from Tibet to Xinjiang, will be enough to bring about responsible behaviour on the part of the CCP.

At the same time, the Indian leadership must refrain from unnecessary muscle-flexing and loose talk, and equally strive to avoid any confrontation in Ladakh.

China is less likely to escalate the situation on its own, but rather leave India with the false impression that tough leadership and a quick buildup of forces are enough to stare down China – and thus continue to neglect its national defence.

Nevertheless, it would be folly to consider developments in Ladakh in isolation from Chinese actions elsewhere along the undefined border with India.

Chinese actions emanating from its close relations with Nepal will have to be closely watched. The Nepal government has already claimed the area of Kala Pani and Lipulekh Pass. This pass, up to which India had recently built a road to facilitate travel by Indian pilgrims visiting Kailash Parbat, can also be a launchpad to intercept the road to Xinjiang.

For a country such as India to hold its own and safeguard its national interests against the China–Pakistan combine, it is imperative to have a military which is strong enough to deter them from attempting any misadventure against this country.

China’s advancement in a range of military technologies, modernization of its forces and gaining influence amongst countries on India’s immediate neighbourhood makes the security scene for India rather challenging. Then there is the possibility of India having to face a two-front war. Our state has overlooked these challenges for too long.

For India, there is no time to lose to upgrade its defence capabilities. Policies can change in a matter of weeks, while military capabilities take years to come about. Our long neglect of defence capabilities cannot be made up through panic purchases of weapons and equipment. Often one can end up with defective equipment, as it happened during Kargil when we landed up with very expensive and faulty artillery ammunition and even coffins of poor quality.

In any case, panic purchases cannot bring about any substantial improvement of a country’s defence capabilities.

India’s security scene is anything but reassuring. The military’s adopting the concept of ‘Integrated Theatre Commands’ is still a work with no progress. No one commander stands designated and charged with the overall conduct of war, and in the process tasking and coordinating the actions of various Commands (or Theatre Commands – as and when they come about).

The CDS is only another secretary in the Ministry of Defence. The recommendations of various committees lie buried in the archives of the Government of India. Hopefully someone will dig these out, dust them off and implement. There is a storm building across the Himalayas.

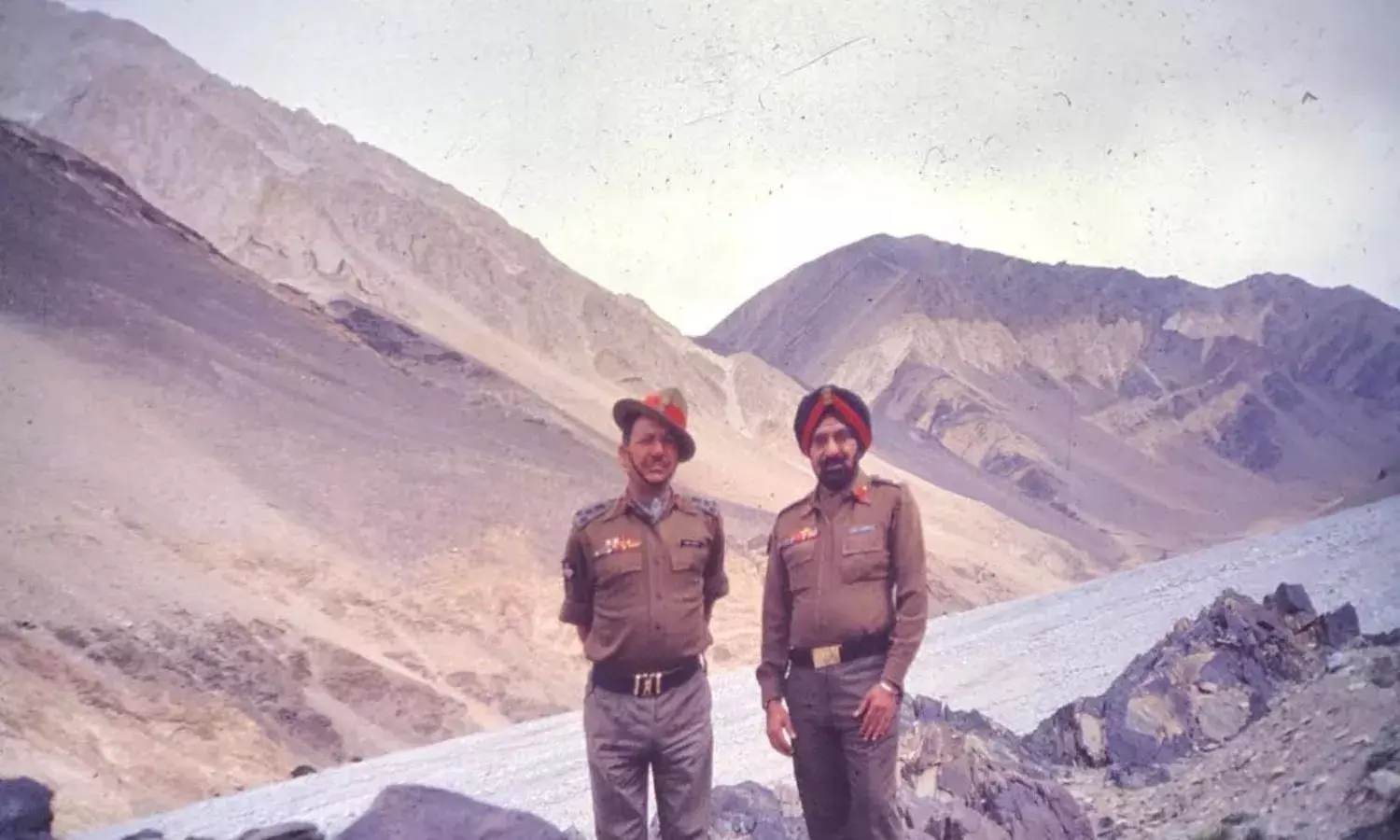

Lt General Harwant Singh (Retd) is former Deputy Chief of Army Staff. Cover Photograph: From the general’s files when he was at Pangong Tso