THE NEW GREAT GAME

'A settlement is always political and execution military’

The compulsions which we must use towards our enemy will be regulated by the proportions of our own and his political demands. In so far as these are mutually known they will give the measure of the mutual efforts; but they are not always quite so evident, and this may be a first ground of difference in the means adopted by each.

Von Clausewitz On War

At the height of British imperialism and Czarist Russian expansionism, both powers vied with each other to safeguard their empires. Resultantly, both carried out moves and counter moves on the chess board of Central Asia, Afghanistan and Tibet with the core concern being to maintain Afghanistan and Tibet as a buffer zone between Russia and the Indian subcontinent.

It was dubbed as the ‘Great Game’ by the British and the ‘Tournament of Shadow’ by the Russians.

Attempts by the British to place a pliant Amir in Kabul resulted in the disastrous First Afghan War 1839-42 and Russian phobia triggered the Second Afghan War 1879-80. At the end of the colonial era the two big states – India and China - were left with the legacy of the game with Tibet as the perceived area of interest and conflict.

For India it still remained a desirable free buffer zone, however, for China it was to be assimilated in accordance with its strategic interests and perceived suzerainty over the region in the past. It was to be the New Great Game. Nevertheless, over the years we have accepted Tibet being a part of China

With the hindsight of history, it would be charitable to say that India being a newly emerged nation with the leadership and institutions lacking experience in handling the complex issue of the legacy of colonialism and independent foreign relations, it did what it did culminating in the 1962 border war.

Post 1962 the then Foreign Minister Vajpayee’s visit to China in February 1979 was indicative of India’s new found confidence and pragmatism which further found expression in Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visiting China December 19- 23, 1988 at the invitation of the Chinese premier. It was a major event in Sino-Indian relations since the heydays of the 1950s and the bitterness post 1962.

Then followed the 1993 Peace and Tranquillity Agreement and other Confidence Building agreements which sought status quo along the frontiers while developing bilateral relations.

However, the 2005 Agreement between the ‘Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the People's Republic of China on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question’ signed at New Delhi on April 11, 2005, was the true indication of the confidence and willingness of both sides to settle the boundary issue.

‘Amongst other articles and the customary diplomatic language, three aspects stand out. Under Article III it was agreed that ‘both sides should, in the spirit of mutual respect and mutual understanding, make meaningful and mutually acceptable adjustments to their respective positions on the boundary question, so as to arrive at a package settlement to the boundary question. The boundary settlement must be final, covering all sectors of the India-China boundary’.

Article VI was explicit in that ‘the boundary should be along well-defined and easily identifiable natural geographical features to be mutually agreed upon between the two sides.’

And Article VII and VIII, perhaps reinforcing Article III, stated that ‘in reaching a boundary settlement, the two sides shall safeguard due interests of their settled populations in the border areas’ as also ‘within the agreed framework of the final boundary settlement, the delineation of the boundary will be carried out utilising means such as modern cartographic and surveying practices and joint surveys.’

It requires no in-depth interpretation to conclude that the Agreement actually put aside past claims and counter claims on historical or cartographic grounds (adjustments to their respective positions) to accept the ground reality and concerns of both sides to come to a mutually adjusted settlement with no major change on the ground (without displacing settled populations) and to delineate and demarcate the agreed border with modern cartographic means which in fact would lay to rest all past maps and markings, often based on inadequate and inaccurate survey depicted on inappropriate scales of maps leading to different interpretations.

It was the acceptance of reality by India which as Mohan Guruswamy writes ‘there seems little or no chance that the Chinese could be persuaded to hand over Aksai Chin to us, thereby de-linking Tibet from Sinkiang. There also seems an equally remote chance that we might be able to retrieve it from the Chinese by military means. Even if we summon the political will to stake a fortune, the sheer lack of any tangible benefits, material or spiritual, will only make this even more foolhardy.’ For the Chinese too it was clear that reclaiming Arunachal Pradesh (South Tibet) by force was no longer a feasible proposition.

It would therefore be logical to ask as to why there was no movement on the settlement for the last fifteen years and where was the plot lost bringing us to the present situation. Perhaps our domestic political compulsions, irrespective of the political dispensation in power in this period, wherein national security issues have progressively become a competitive matter of exaggeration and magnification of minor tactical actions on the borders by the ruling party and any setback, actual or perceived, is painted as a sell out by the opposition leaving no scope or ground for serious and pragmatic debate for resolution with national interest in focus.

On the other hand, for the Chinese, Aksai Chin was a strategic concern needing security and resolution.

As veteran journalist Prem Shankar Jha writes ‘China is undoubtedly the country that has triggered the confrontation. But it should be apparent to those not numbed by hyper-nationalism, that it has not done so simply to grab a sliver of additional territory in the Himalayas, whose economic value to it is less than negligible. If we can give credence to the statements of the foreign office in Beijing and the Chinese embassy in Delhi, China has acted the way it has because it believes India is no longer abiding by the understandings upon which the 1993 Agreement on Peace and Tranquillity in the Border Areas, and its subsequent elaboration in 2005, were signed, and has therefore ceased to be a reliable treaty partner’ and further writes that ‘Today, 15 years later, China has, by and large, kept its side of the bargain…’ That may be an extreme view, however, our political and military utterances have been contrary to the text of the agreement.

The concept and terminology of LAC (Line of Actual Control) has no standing or sanctity in expressing international borders between nations and is also not binding in legal terms. It was a working construct to define where opposing troops and physical presence existed. In other words, whatever was actually under control of both sides. By the same token it could be altered by force which the Chinese have done in Eastern Ladakh.

While the analysis, views and theories doing the rounds of academic circles, seminars and TV panel discussions may suggest the aim, motive and long-term strategic purpose of Chinese actions, and the threat to India, the Chinese would not have planned and executed this move on such a large scale to simply withdraw after discussions. That they are there to stay is clearly indicated in the Moscow Statement of September 10, 2020 which finds no mention of status quo as on April 2020 or any reference to the term LAC and their subsequent assertions.

Consequently, the troop deployment by both sides is very unlikely to be diluted. A militarised line separating the two is there to stay. That would be the oft stated ‘long haul’ and not just tiding over the logistics this winter.

A common refrain and counter argument in all forums on the question of a settlement is the issue and perception of trust, which is a deeply ingrained perception over the decades, militating against any settlement with the Chinese. Given our experience and inadequacy of capabilities to meet such developments on the border, the need was and is to ensure building our capability and streamlining our national security structures to handle any situation arising out of ‘lack of trust’, which we did not, rather than ascribe such challenges to ‘betrayal of trust’.

National security and interests are not secured on trust, good faith and diplomacy alone, they are secured with the backing of hard power. Whether we settle the boundary with China or not, hard power will remain an imperative and important constituent of comprehensive national power and any meaningful diplomacy.

Macho militarism created by media hype, not backed by adequate capability and sterile diplomacy again without hard power, cannot attain national objectives. We have a convoluted history of handling the border question with China over the decades since independence. Perhaps a benevolent rationalisation would attribute it to missteps by individuals and institutions lacking experience in handling strategic issues, however, seven decades is a long time to lose our innocence.

We can curse or regret past actions but cannot be held hostage to our past and leave a similar legacy for the future. The situation on our northern borders is a tangled web created by politics and diplomacy and expecting the military to unravel it through border talks is an unrealistic expectation.

A settlement is always political and the execution military. Besides serving the limited and immediate purpose of imposing some restraint on both sides, it cannot obviously settle anything in the long term.

However, if the existing ground situation is accepted as normal, and bilateral trade, commerce and other relations are restored as well as studied neutrality is maintained on the questions of Sinkiang and Uighurs, Tibet, the Dalai Lama, Taiwan and South China Sea, as suggested by the Chinese, it would be a humiliating sell out amounting to abject capitulation.

Any agreement to mutually pull back troops from the present positions would mean giving up ground held by us as also accepting ground occupied by the Chinese.

Perhaps the situation can be turned around to our advantage by shedding the baggage, diffidence and ‘good faith’ of the past six decades. ‘Never let a good crisis to waste’, they say.

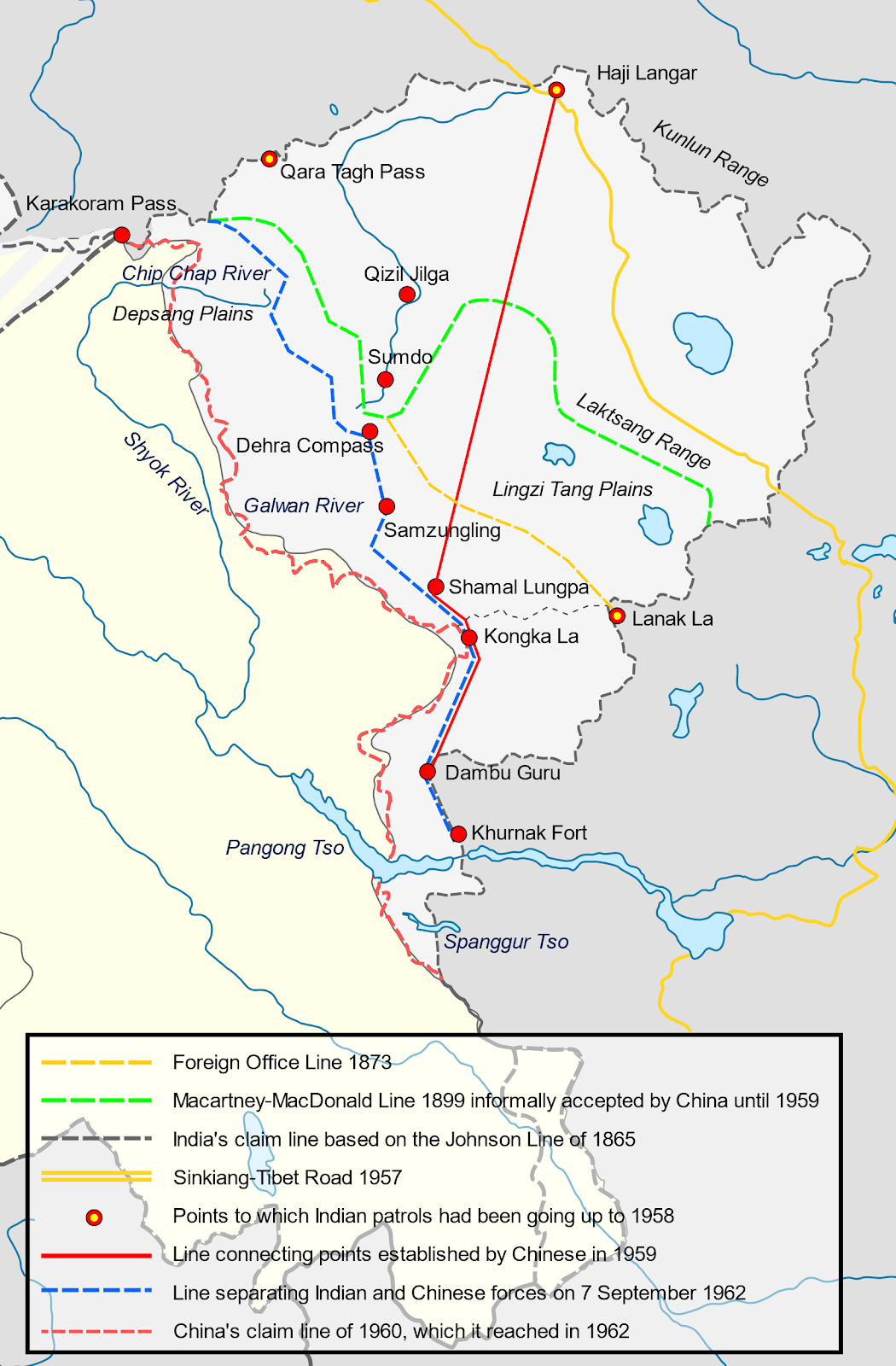

Given that both sides cannot substantially alter the ground situation and that we can and will hold what we are holding, a bold and open offer can be made by us to settle the boundary along the Mac Mohan Line in the East and the McCartney-MacDonald Line of 1899 in the West with minor and appropriate adjustments.

This would place the onus of settlement on the Chinese along with reinforcing the legitimacy of our offer based on the McCartney-MacDonald Line, formally presented to the Chinese in 1899 and accepted by them till 1959, and not what they call the 1959 line now.

This would entail the Chinese pulling back appropriately East of the present position and address our internal political conundrum and sentiments related to ‘not losing an inch of territory’ besides yet assuring the Chinese security of their Highway 219 connecting Sinkiang with Tibet. Till there is a positive and accommodative response, all adverse economic, diplomatic and strategic linkages against the Chinese should be exercised.

Notwithstanding a settlement or otherwise, China will remain a rival, competitor, adversary, threat or enemy depending on shifting equations and interests. We need to be prepared to handle it appropriately for a long time to come.

Lt General NS Brar is former Deputy Chief Integrated Defence Staff and Member Armed Forces Tribunal.