The Hokus Pokus About the Quad and AUKUS

SAEED NAQVI

Robert Blackwill, US ambassador at the time of anti terror fireworks over Afghanistan, had established a tradition of seating guests at lunch around a circular table, where he grandly held forth, initiating a discussion. “Imagine I am Henry Kissinger” would be one of his opening gambits. An idea was tossed up. A discussion followed. The one who spoke the most, ate the least, because all plates were removed in one swoop.

On one such occasion, before soup was served, the ambassador announced with considerable satisfaction that Pakistan’s President Musharraf had decided to join the global war on terror as the frontline state.

Seated to my right the late Pranab Mukherjee, was agitated. He whispered his anger to me. It was uncanny. What he whispered was exactly the question shaping up in my mind. I raised my hand: “You are aware that New Delhi had complained consistently about cross border terrorism from Pakistan particularly since 1989.” Pranab Da (as Mukherjee was affectionately addressed) completed my question in his typical arrangement of words: “It is most worrying no doubt – you now have Pakistan as the frontline state in your war against terror?” pause. “They perpetrate terror against this country.”

Blackwill spoke volumes in two brief sentences: “Musharraf has joined us in our global war on terror. What you are talking about is your old regional quarrel.” Juxtapose this with the Quad-AUKUS equation.

Atal BIhari Vajpayee, as Prime Minister, had hosted President Bill Clinton for five full days in January 2000, just the previous year. Clinton spent just five hours in Islamabad, mostly chastising Musharraf for disrupting regional peace since Kargil. New Delhi was in seventh heaven. Terms of endearment with Washington had radically altered.

In a little over a year, had George W Bush reversed that equation? Pakistan was incorporated into the global war on terror even as New Delhi cried foul. Pakistan was in the “A” team against terror; we were not.

Likewise, there is this idea of Quad in which New Delhi is such an enthusiastic participant. Australians and the Japanese did, frequently, vent their skepticism, invested as they were in the Chinese economy. After the American debacle in Kabul, however, Tokyo’s misgiving on Quad was all over the Japanese media. The hemorrhage had to be forestalled.

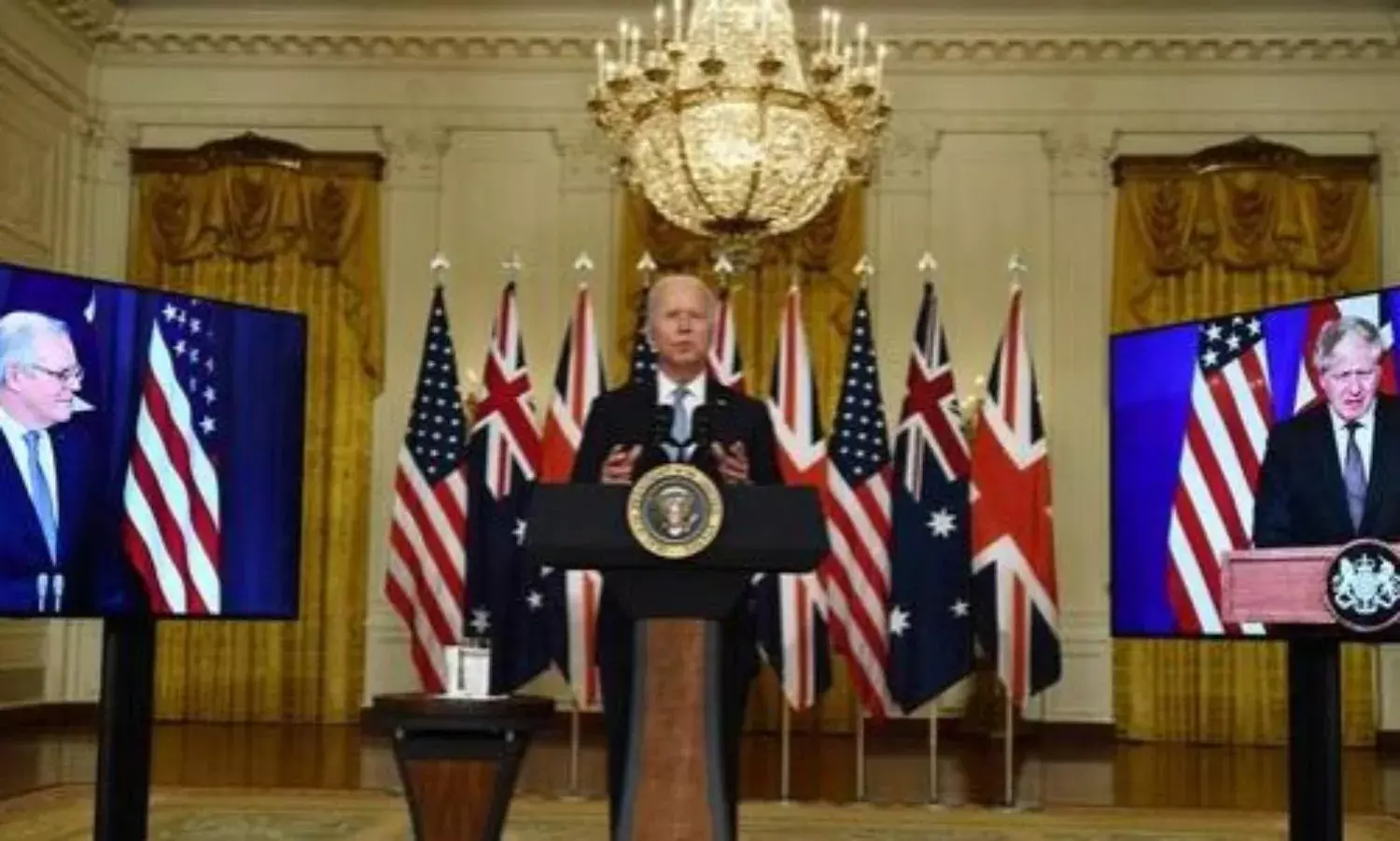

With the suddenness of revelation came the announcement of AUKUS (Australia, UK, US), the powerful military alliance in the Indo-Pacific of which India alas, is not a partner. So New Delhi is trying to pack content into an abruptly devalued Quad.

Did Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s photograph with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison on the margins of the UNGA, flatter New Delhi? Pardon my complexes, does not a leader wearing AUKUS plus Quad badges dwarf the one with a frayed Quad pinned to the lapel?

I would not go as far as the wag who takes the uncharitable view that the US takes India for granted exactly as secular political parties regard the Muslim vote: where else can they go?

AUKUS must have been in the works for some time but it sprung upon the world when the US felt the earth move from beneath its feet in Kabul. The furious response from France only disguises anger in the EU which is talking of security outside NATO. That AUKUS is a purely Anglophone grouping should not be a surprise. Games have been played before to keep some clubs racially segregated.

For instance, when the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 placed a question mark on the need for NATO, Margaret Thatcher, then on a trip to Helsinki, was asked by a reporter: Now that the Soviet threat has gone, what was the justification for Britain’s nuclear deterrent?

Thatcher shot back “We still have a problem in the Middle East.” Thereafter, along with George Bush the senior, she began to put together “a coalition of the willing” ostensibly to oust Saddam Hussain from Kuwait. Saddam-in-Kuwait was the ignition point, not the larger perspective against which Operation Desert Storm of 1991 was designed.

Anglophone dominance of the world order since World War II, faced a challenge. Soviet collapse had brought about a reunification of Germany. This at a time when the Japanese economy was booming. It was easy to raise the spectre of AXIS, without actually mentioning the “A” word.

France, always ready with its own compass to navigate world affairs, initially dragged its feet on the coalition led by US and UK. President Francoise Mitterand was among the last to join the “coalition of the willing”. It was the biggest military coalition since 1945 – a grouping of 39 countries. Given their obsession, Pundits may be interested to know that Pakistan was part of that coalition.

As one who covered the story from Baghdad, I am possibly the only Indian witness who can confirm that the show was run exclusively by the US and Britain. There were two separate press briefings, for the US and British media by their respective spokesmen. French journalists, like the lonesome me, were on the outside. It may be added in parenthesis, that the British media on this occasion were the poor cousins.

From the terrace of the Al Rashied hotel, Peter Arnett of CNN inaugurated what came to be known as the global media. The war was brought live into the world’s drawing rooms. John Simpson of the BBC, by comparison, cut a sorry figure, walking around with a satellite telephone. It was only after being beaten by CNN during Operation Desert Storm that the BBC World Service TV was launched.

To revert to AUKUS, yes the French fury is understandable. Not only was a $90 billion submarine order being stolen, but an Anglophone dominated world order was being perpetuated. This is what infuriated President Emmanuel Macron. It just so happens that the turn of events has also provided Macron with an occasion to fall back on a de Gaulle style nationalism just when his ratings are plummeting and all manner of candidates are tossing their hats in the ring for the next elections.