1971 : The Race to Dacca

A view from the Indian Army HQ's Military Operations Directorate

There was jubilation in the MO Dte Ops Room on 11 December 1971 as the race for Dacca had commenced. In MO Dte, as perhaps elsewhere, the focus had shifted to activities in the Central and Eastern Zones. In the Central Zone, I Maratha LI (JANGI PALTAN) had secured Jamalpur and in the Eastern Zone, troops and equipment were being airlifted across the River Meghna opposite Brahmanbaria.

It came to light later on that on December 10, Niazi had informed the Pakistan GHQ that India had heli-dropped a brigade size force south of Narsingdi and para-dropped a brigade in Tangail. In fact, it was just 2 PARA (Maratha) in Tangail and not a brigade.

Apparently, Niazi had desperately asked that the promised foreign help should reach East Pakistan by first light December 12. Instead, he received a false hope from the Pakistani CGS Gen Gul Hassan: “White friends [Americans] will come from the south and Yellow friends [Chinese] will come from the north.”

On the evening of 11 December, 2 PARA (MARATHA) (Lieutenant Colonel K.S. Pannu in command) was dropped in the Tangail area. The battalion secured the Poongli Bridge by 2000 hours and soon thereafter intercepted about 300 enemy troops withdrawing from the area. News of the success of the paradrop reached us only in the morning of 12 December, since the battalion was out of radio contact throughout the night.

On 12 December 1971, the historic linkup between two Maratha Battalions: I Maratha LI (JANGI PALTAN) and 2 PARA (old 3 Maratha LI) was affected at the crossing of the Poongli Bridge across River Turag amidst much jubilation. The next spot of resistance near Tangail was removed by two companies of the Marathas under the command of Maj Satish Nambiar, resulting in the capture of Brig Kader of Pakistani 93 Inf Bde, along with seven officers. For this action, Maj Nambiar was awarded the Vir Chakra.

In order to facilitate better coordination for the battle of Dacca, the Army Commander placed 101 Communication Zone Area under the command of IV Corps with effect from mid-day on 15 December 1971.

On 14 December, General Nagra commenced advance on three axes with both 95 and 167 Bdes. The latter established a block in the Gachha area, in the early hours of 16 December.

By now elements of IV Corps had crossed the Meghna River and were threatening Dacca.

Earlier on December 14, Gen Yahya Khan had sent a signal to Niazi and the Governor Dr Malik. Yahya praised them for fighting a heroic battle against overwhelming odds and asked Niazi to take all necessary measures to stop the fighting and save lives of armed forces personnel from West Pakistan and of loyal elements.

On the same day, at 11:15 AM, three Indian MiGs attacked the Government House and bombed the main hall where an emergency meeting of the cabinet of the provincial government was usually held. The bombs ripped the massive roof of the hall. Governor Malik rushed to the air-raid shelter and reportedly hiding under a table scribbled out his resignation (we learnt of these events only afterwards)!

On that day the governor and his whole cabinet took refuge at Hotel Intercontinental, which had been converted into a Neutral Zone by the International Red Cross. This was meant for the international community staff who were working inside the war zone. But most of West Pakistani VIPs, including chief secretary, inspector general of police, commissioner of Dhaka Division and provincial secretaries "dissociated" themselves from the government in writing and crowded into the hotel.

After receiving a message from President Yahya, General Niazi on the evening of December 14 decided to initiate necessary steps to obtain a ceasefire. He was seeking someone as an intermediary. He first thought of Soviet and Chinese diplomats, then finally chose the US consul-general in Dhaka. Gen Niazi and Rao Farman Ali both went to the office of Mr Spivak and asked him to negotiate ceasefire terms with the Indians. Mr Spivak agreed only to forward a message.

Hence, it was through the US consul-general in Dhaka that a message from Niazi and Rao Farman Ali reached our Chief of Army Staff General Sam Manekshaw, requesting an immediate ceasefire. The message sought guarantee of safety of Pakistan armed forces and protection from reprisals by Mukti Bahini. The following day Sam Manekshaw replied that “a ceasefire would be acceptable and the safety would be guaranteed only if the Pakistani Army surrenders to his advancing army”.

From December 14, the civil government of East Pakistan had ceased to exist. The military generals also were looking desperately for ways for a ceasefire or surrender, with a view to end the war and save their lives. They were worried about the wrath of highly agitated locals and freedom fighters and frantically sent messages to their bosses in West Pakistan and sought approval for a safe exit.

On the morning of December 16, 1971, two battalions of the Indian Army, one each from 95 and 167 Mountain Brigades of the Central Front were at the doorstep of Dhaka. Similarly, a brigade group of the Eastern Front was threatening Dacca from the East.

On the morning of 16 December, Maj Gen Nagra, GOC 101 Communication Zone Area, along with freedom fighter Kader Siddique had arrived and was at the Mirpur Bridge (at present Gabtoli) and from there he had sent a message directly to Niazi. He wrote: “My dear Abdullah, I am here. The game is up. I suggest you give yourself up to me, and I will look after you.”

The scene when Niazi received the message was later described by Rao Farman Ali and Siddiq Salik’s memoirs. Salik wrote, “Major-General Jamshed, Major-General Farman and Rear-Admiral Shariff were with General Niazi when he received the note at about 9 AM. Farman, who still stuck to the message for ‘cease-fire negotiations’, said, ‘Is he the negotiating team?’ General Niazi did not comment. The obvious question was whether he was to be received or resisted. He was already on the threshold of Dacca.

“Maj Gen Farman asked General Niazi, ‘Have you any reserves?’ Niazi again said nothing. Rear-Admiral Shariff translating it in Panjabi, said, ‘Kuj palley hai?’ (Have you anything in the kitty?) Niazi looked at Jamshed, the defender of Dacca, who shook his head sideways to signify ‘nothing’. ‘If that is the case, then go and do what he asks,’ Farman and Shariff said almost simultaneously.”

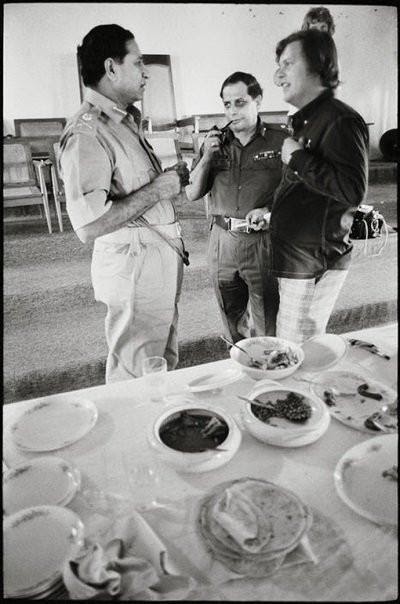

Gen Niazi, Gen Jacob and Gaving Young, a British journalist during lunch at Dhaka Cantonment, 16 December 1971, shortly after Gen Jacob persuaded Gen Niazi to surrender. Photo: Magnum Archives

In a later interview with the Indian newspaper The Tribune, Nagra remembered the day vividly. He said: “…when I walked into Abdullah’s (Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi) office in Dacca, there was instant recognition. General Niazi had put on some weight, though his face still had the same glow.

“Hello Abdullah, how are you?” I asked him.

“Abdullah broke down and exclaimed: ‘Pindi mein bethe hue logon ne marwa diya’ (The people sitting in Pindi doomed us). I let him talk to lighten his heart. There were reminiscences. Tea followed and of course there was forced friendliness. The rest is history.”

(This scene bore a bit of irony because Niazi and Nagra had both got commissioned in the British Indian Army on the same day. So, it was sort of two classmates meeting after a long time.)

Kader Siddique in his memoir “Swadhinata ’71” wrote: “Introducing me to Niazi, Gen Nagra said, ‘Meet this man, the sole representative of Mukti Bahini, for whom you could not close your eyes even for a night’s sleep.’ …At the mention of my name Niazi instantly stood up from his chair, saluted and extended his hands for a shake, which Siddique declined. Nagra said, ‘There is no problem shaking hands with a defeated commander-in-chief. In fact, it’s the gesture of a hero.’”

For the Joint Forces of the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini, capturing Dacca had to be brief and quick. In reality, it was so quick and brief that even the top brass of the Joint Command became a little baffled. Dacca, the fortified bastion of the Pakistani occupation forces, fell like a house of cards!

The Surrender

On December 16, General Jacob flew in from Calcutta. Touching down at Dhaka, he went directly to the Headquarters of Pakistani Eastern Command and showed Niazi the written instrument of surrender which he had drafted.

All the generals including Rao Farman Ali protested. They said it was a ceasefire arrangement they could sit for, not a surrender, let alone in a public ceremony and to the Joint Forces.

In his memoir ‘Surrender at Dacca’ Gen Jacob has an elaborate description of the tough negotiations: “I was a little annoyed and pulled Niazi aside. ‘I have been talking to you for three days,’ I told him. 'I have offered you terms that you will be treated with respect and under Geneva Convention. We will protect all ethnic minorities and everyone. If you surrender, we can protect you. If you do not surrender, I wash my hands off anything that happens.’”

Then Gen Jacob conveyed the 30 minutes ultimatum to decide on a surrender or face the consequences and he then left the room.

Thirty minutes later, as Gen Jacob re-entered the room, he wanted to know the decision. Gen Niazi was silent. Gen Jacob picked the surrender document lying on the table and said, “I take it as accepted.”

He said in a resolute voice, “General, you will surrender on the Race Course in front of the people of Dacca.”

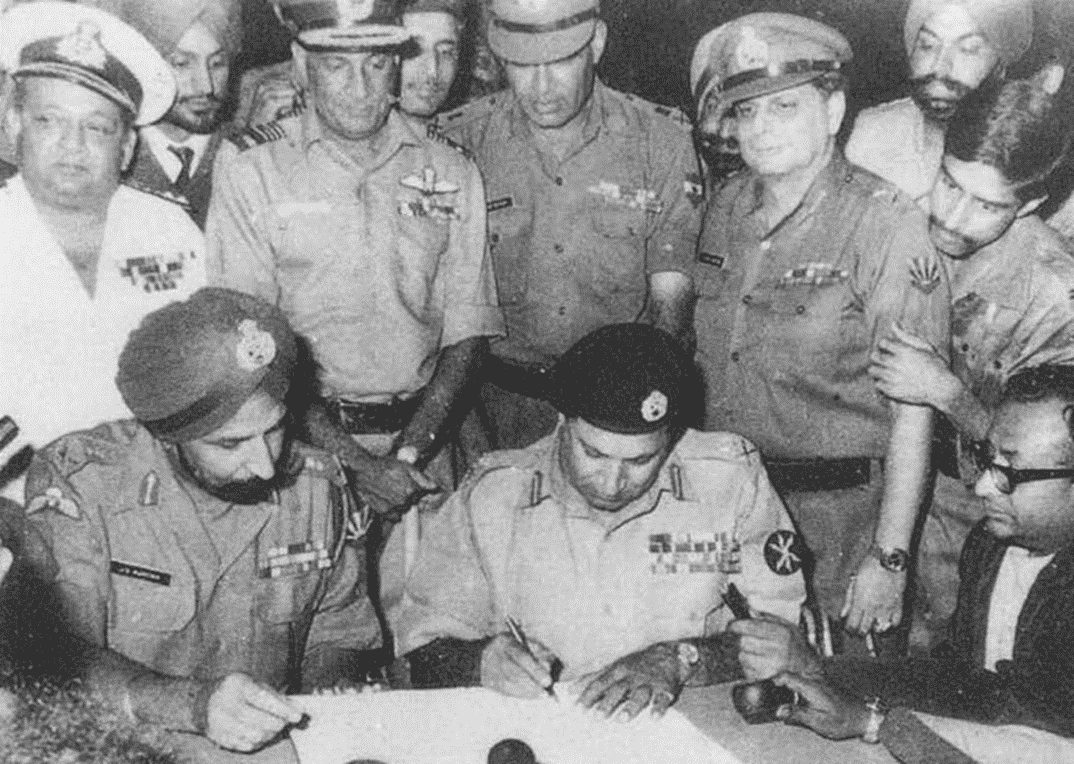

Gen Niazi signing the Instrument of Surrender under the gaze of Gen Aurora.

Photo: collected

At around 4:30 PM, General Jagjit Singh Aurora, GOC-in-C Eastern Command, arrived at the Dhaka airport. Jacob and Niazi went there to receive him. Among the entourage was AK Khandoker, the Deputy Chief of Staff of Mukti Bahini. The Chief of Staff was not there as he was busy in Sylhet in a military operation.

“Once the signing was over, the two commanders rose from their chairs. Then according to the tradition of surrender, General Niazi with a trembling hand and a melancholic face handed his revolver to Aurora.”

And thus ended the last chapter of the nine-month-long war that saw untold bloodbath and emergence of a new nation – Bangladesh.

In MO Dte, the flurry of work gave way to relief. Since I was not on duty that night, I celebrated the victory with my Canadian colleague of Staff College, Major Allan Clarke, his wife Sue and their two small children who were staying in the Oberoi Hotel. After a night of revelry, I made my way back to my room at the Central Vista Mess and passed out for the next couple of hours!

CONCLUSION

The 1971 War between India and Pakistan was unique in many ways. Unlike earlier wars of India, it was India that had the initiative and planning and preparations were carried out in detail. Intelligence about the enemy was good as the Bengali population of Pakistan supported India. There was good coordination between the three services, despite the lack of formal joint structures, and after initial pressure on the military to act fast, the viewpoint of the military had prevailed.

For a change, all or most Ministries and Departments of the Government acted in sync and the entire nation rose to support the war effort.

Internationally, political and diplomatic efforts had succeeded in near global support for India, despite the biased pro-Pakistan attitude of the United States and the fence-sitting attitude of China. The India-Soviet Union Friendship Agreement was pivotal in its scope as it adequately countered USA.

Another difference was it did not involve the issue of Kashmir, but was precipitated by the crisis created within Pakistan by the political battle between Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, leader of East Pakistan and the Yahya-Bhutto combine, leaders of West Pakistan.

The international community was surprised at the war’s fast pace, and many militaries of the world took time out to study the war in detail, especially the operations in the Eastern Front.

The war led to the birth of a new nation, Bangladesh. Militarily, it was the greatest victory of India that resulted in the surrender of 93,000 Pakistani military personnel – the largest number of prisoners taken in any war after World War II.

In the Eastern Front, while some formations and units continued to operate in the classic set-piece attacks mode, others stepped up the pace by carrying out out-flanking moves, by-passing, use of transport air support for making air-bridges across major rivers, all of which exploited offensive and fast-moving operations.

Let me conclude with the following narrative, which is not well known, but one that highlights the impact of offensive achievements on the nation’s leadership.

After the war, B.B. Lal, who was the Defence Secretary, told Sagat (Lt Gen Sagat Singh, GOC IV Corps) an interesting story regarding the crossing of the Meghna.

On 10 December a meeting was being held in South Block, chaired by Sardar Swaran Singh, the Minister of External Affairs. Attending the meeting were the Defence, Home and Foreign Secretaries, the Director of the IB, and the Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister.

The meeting had just commenced when the message arrived that Sagat had crossed the Meghna. The Defence Minister, Babu Jagjiwan Ram, rushed in soon afterwards, while the Prime Minister’s Principal Private Secretary ran to her office to inform her. According to Lal, very soon afterwards, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was seen running down the corridor, her hair and saree flying. They were all surprised to see the Prime Minister bubbling with joy, and for him, this was the most unforgettable moment of the 1971 War.

Concluded.

Lt Gen Vijay Oberoi, PVSM, AVSM, VSM is an infantry officer (The Maratha Light Infantry) and a former Vice Chief of Army Staff. Despite losing his right leg in the 1965 India-Pakistan War he soldiered on till his retirement on September 30, 2001. A prolific writer and analyst, he was founder director of the Indian Army’s think tank, the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) for five years where he is now director emeritus. He is founder president of the War Wounded Foundation, set up for meaningful rehabilitation of war disabled personnel