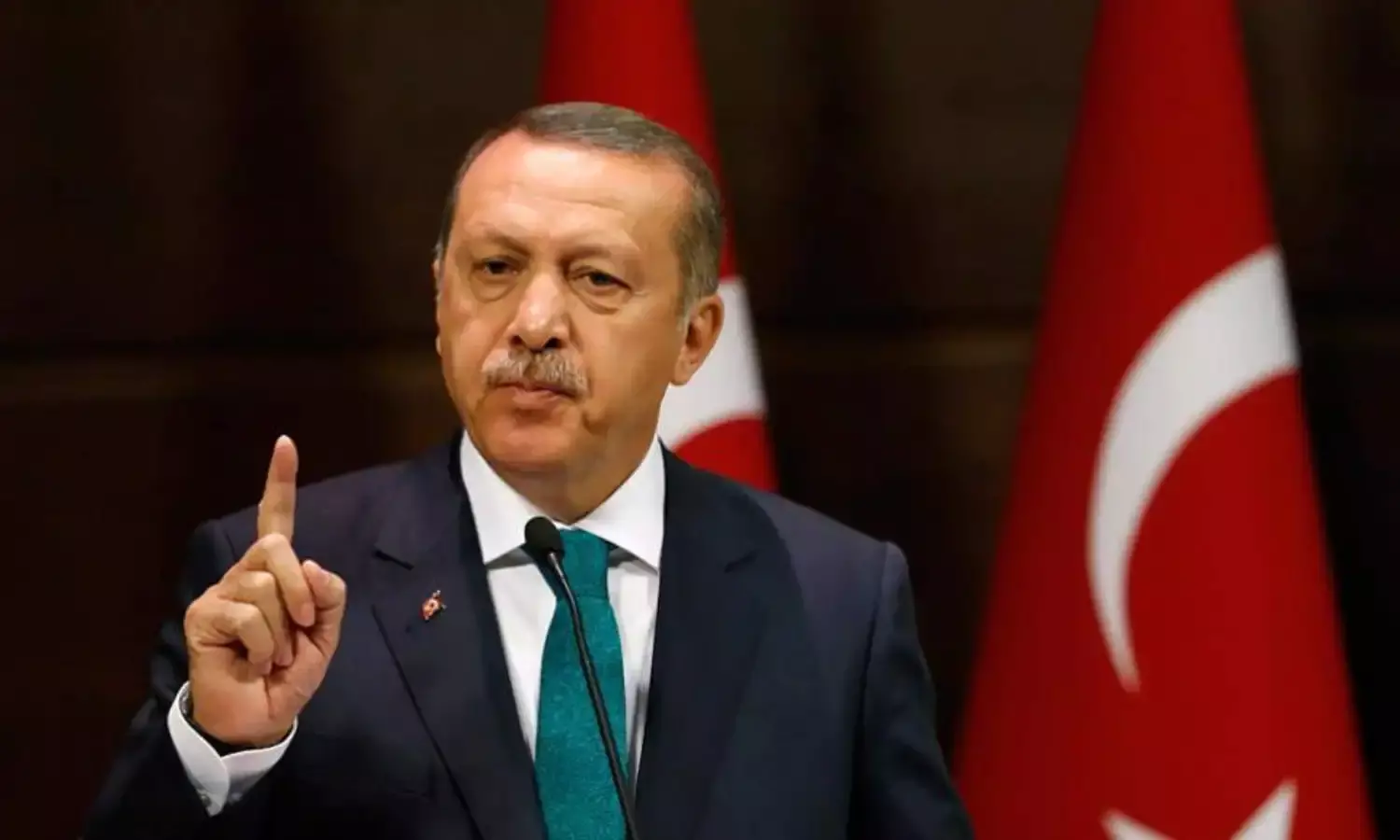

Erdogan's Quest For Absolute, Unquestioned Power

Presidential elections in Turkey

A quest for absolute, unquestioned power; a sense that the Turkish offensive against the Kurdish YPG in Syria would have refurbished his nationalist credentials; and concern that disaffection could increase with Turkey’s slowing economy, possibly prompted Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to suddenly call for early general elections on June 24-more than one year ahead of schedule. Explaining his own rationale for calling early elections President Erdogan said economic challenges and the war in Syria meant Turkey must switch quickly to the powerful executive presidency that would go into effect after the vote.

He possibly also banked on the political disarray in Turkey caused by the mass arrests after the abortive coup of 2016 which he blamed on his one-time ally U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gulen and his followers. According to the United Nations nearly 160000 people including leaders of political parties; senior media personalities; army and air force officers and many others had been arrested for being part of the Gulen “conspiracy”. The state of emergency imposed by Erdogan following the abortive coup remains in force and the Presidential and Parliamentary elections would be held under the emergency- a development opposed by leaders of the opposition and even by old time, though somewhat estranged ally, the USA. US State Department spokeswoman Heather Nauert told the media “…During a state of emergency, it would be difficult to hold a completely free, fair and transparent election in a manner that is consistent with ... Turkish law,”. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) is planning to deploy 28 long-term and 350 short-term observers to follow Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections on June 24.

Turkey has a unicameral parliamentary system set up under the 1982 Constitution. Parties which have at least 20 deputies can form a parliamentary group. Currently there are four parliamentary groups at the Grand National Assembly- the AKP or Justice and Development Party to which the President belongs and which has the highest number of seats; the CHP or Republican People's Party led by Kemal K?l?çdaro?lu; MHP or Nationalist Movement Party led by Devlet Bahçeli; the HDP or Peoples' Democratic Party led by Selahattin Demirta?. To avoid a hung parliament and excessive political fragmentation a party must win at least 10% of the national vote to qualify for representation in the parliament. Candidates without political parties need to secure 100,000 signatures from the public.

There are now 600 members of parliament. The number was increased from 550 to 600 in 2018. They are elected for a four-year term by the D'Hondt method, a party-list proportional representation system, from 87 electoral districts. In the November 2015 parliamentary election, a total of twelve parties fielded candidates but failed to secure representation in the legislature.

The Presidential elections are conducted in a two round system with the top two candidates contesting a run-off election two weeks after the initial election should no candidate win at least 50%+1 of the popular vote. Turkey is split into 87 electoral districts, which elect a certain number of Members to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. In all but three cases, electoral districts share the same name and borders of the 81 Provinces of Turkey. The exceptions are ?zmir, ?stanbul, Bursa and Ankara. The Grand National Assembly has a total of 600 seats, which each electoral district allocated a certain number of MPs in proportion to their population. The Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey conducts population reviews of each district before the election and can increase or decrease a district's number of seats according to their electorate.

In 2017, the population of Turkey was estimated to be 80.8 million with a growth rate of 1.24% per annum. The population is relatively young with 23.6% falling in the 0–14 age bracket. The Supreme Election Board Chairman Sadi Güven has said that there are a total of 59.4 million eligible voters in Turkey and abroad. The number of first-time voters is 1.65 million, while a total of 180,869 ballot boxes will be set up on polling day. Turkish expats will vote in 60 countries at 123 diplomatic representations.

The Turkish Parliament has created a conducive atmosphere for Erdogan. It passed a law revamping electoral regulations that the opposition said could open the door to fraud and jeopardise the fairness of voting. The law grants the High Electoral Board the authority to merge electoral districts and move ballot boxes to other districts. Erdogan had also won a referendum to change Turkey’s form of government to an executive presidency, abolishing the office of the Prime Minister and giving the President more powers- powers that he would be able to exercise if he were to win the election. These include the freedom to rejoin the political party to which the President belongs discarding the tradition of an impartial president. The President would have control of the budget and cabinet and judicial appointments. The President would be allowed to stand for two more terms. He would have the power to dissolve parliament and issue decrees that could not be scrutinised by parliament or courts, unless a supermajority votes against him. He would also gain substantial immunity from prosecution. According to the new system, ministers will not be chosen from Parliament and lawmakers will have to resign from Parliament if they are offered a place in the Cabinet.

While Erdogan appears supremely confident that he will win there remains the possibility that some of his actions might impact on voter sentiment. In fact Energy Minister Berat Albayrak –responding to speculation in Ankara--said that Turkey will not hold snap elections even if President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an gets elected as president but the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) fails to win a majority in parliament. He even mentioned a possibility of a run off in the Presidential election but emphasised that Erdogan would win. Erdogan had said he would step down only when the people said “ enough” or “ tamam”. The opposition quickly seized on the word and launched a viral Twitter campaign saying “ tamam”

The Turkish innate nationalist temper and pride in their army could be irked by the mass arrests and prosecution of army and air-force officials. The Ataturk defined constitutional secularism democracy and freedoms, where the census does not identify a citizen’s religion, could be seen as being usurped by Erdogan’s oppression of the media and political parties and his overt support for Islamic symbols. There is, according to reports, a worsening of women’s rights and possible disenchantment among the youth and women with the Erdogan and AKP engineered increasing Islamisation of Turkey.

The call that early elections would be held had caught Turkey off guard. In order to present a somewhat meaningful opposition more than a dozen Turkish opposition lawmakers switched parties in a show of solidarity. Officials from the pro-secular Republican People’s Party, or CHP, said 15 of its lawmakers would join the centre-right Iyi Party saying the decision was a result of ensuring a “democratic disposition”. As a result of the transfers from CHP, the Iyi Party, which means “Good Party”, now has 20 lawmakers in Parliament, satisfying an eligibility requirement. Media reports said that there are eight political parties in the race. They include the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), ?Y? (Good) Party, MHP, Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), Free Cause (Huda-Par) Party, Felicity (Saadet) Party and Patriotic (Vatan) Party. The opposition has been angry both about the changes in the electoral system and accusations that their leaders were party to the 2016 coup attempt. CHP leader Kilicdaroglu said in a speech to members of his party in Ankara “…The political arm of the Gulenist network is the person who is occupying the presidency,”—a reference to Erdogan’s one time friendship with Gulen . The CHP also protested the holding of elections under the emergency demanding that it be lifted before the elections.

The AKP released a 360 page manifesto. Broadened freedoms and rights, a stronger administrative system and a strong economy are among the main promises announced by Erdo?an. He said “The new era will be the era of a strong parliament and strong government. These two basic powers will be complemented by an independent judiciary. In the new period the parliament will be stronger, the government will be stronger and the independent judiciary will be more effective,” . But manifesto is silent on reviving the Kurdish peace process unlike past manifestos of the party. It only said that the decades-long Kurdish question was a matter of democracy. Earlier before the release of the manifesto Erdogan had said new operations would be added to the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch operations against the Kurds till not one terrorist is left.

He has articulated his determination to take greater control of the economy after the elections effectively blunting the Central Bank’s financial authority. Erdogan is on record as having said that interest rates were the “mother and father of all evil”, a controversial comment that prompted a sharp loss in value of the Turkish lira. He had repeatedly urged the central bank to cut interest rates to stimulate economic growth but economists cautioned that a tighter monetary policy was needed for an economy whose currency had lost over 12 per cent in value in the last three months and inflation was running at 10.85pc. He had eventually been persuaded to agree to a rise in the rates in the face of increasing inflation and a flagging economy.

While the AKP and particularly Erdogan have been proponents of more Islamisation, in the Turkish town of Konya, the Ministry of Education brought out a report titled “The Youth Are Sliding to Deism”. Erdogan rubbished the report’s findings which said that even students in state-sponsored religious “imam hatip” schools were not accepting archaic interpretations of Islam and some imam hatip students had begun questioning the faith. Instead of adopting atheism, the report said, these post-Islamic youth were embracing a form of “deism,” or the belief in God but without religion—something just short of atheism. While supporters of the government claimed a Western conspiracy behind the talk of ‘deism’ the erosion of Islam among young people has been an oft-repeated theme in the Turkish public sphere. Articles by Turkish authors have suggested that despite the conviction among religious conservatives that they are in the midst of a golden age, something very fundamental is slipping out of their hands, as “the new generations are getting indifferent, even distant, to the Islamic worldview.” The disenchantment of the youth with the Islamisation process is being traced to their perception of the name of Islam being exploited for political reasons and the name of Islam being tarnished by all the corruption, arrogance, narrow-mindedness, bigotry, cruelty and crudeness.

Erdogan does not have a clear field like Egyptian President Sissi did. During the 2017 referendum to change the system, reports said that Erdogan was able to count reliably on only about half the nation’s vote. Muharrem ?nce is the CHP’s presidential candidate. ?Y? Party leader Meral Ak?ener, a former interior minister and serious challenger and (SP) leader Temel Karamollao?lu had been able to collect the required 100,000 signatures to qualify to run in the presidential elections and Homeland Party (VP) leader Do?u Perinçek also secured the required 100,000 signatures. The Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) had named its imprisoned leader Selahattin Demirtas as its candidate and his campaign would be launched in simultaneous rallies in Istanbul and the majority Kurdish city of Diyarbakir.

The MHP allied to the AKP released a manifesto that called for “National Revival, Blessed Uprising,” ; reforms to bring economic relief to farmers, retired people and families of the disabled, martyred, and veterans. It emphasized five topics, including “smart state and public administration,” “justice,” “combatting corruption,” “multifaceted and multi-dimensional foreign policy,” and “industrialization and SMEs.” The MHP has also pledged early retirement for veterans, employment for the children of martyred people and increase in salaries of their parents. The party has also vowed to grant amnesty except for those who were put behind bars in terrorism-related crimes—including the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETÖ) members—child abusers, rapists and murderers.

The main opposition party the CHP focused primarily on the restoration of freedoms and people’s rights. At rallies Muharrem ?nce, vowed to liberate Twitter from content removal requests in Turkey and reopen Wikipedia in the country. He also said that citizens’ freedom to criticize the president of Turkey is a must in order to remain creative and productive. The CHP promised to establish a “Middle East Peace and Cooperation Organization” with Iran, Iraq and Syria and to transform the region into a field of peace through various infrastructural projects. The CHP faced some criticism when it released its list of candidates which did not include 58 of its current members of parliament. CHP leader Kemal K?l?çdaro?lu defended the changes which had prompted speculation that the new list was prepared exclusively by K?l?çdaro?lu and excluded lawmakers close to the party’s presidential candidate, Muharrem ?nce. ?nce has twice challenged K?l?çdaro?lu for the party leadership in the past.

Women have traditionally been active in the political sphere. Turkey had two parties founded by women –the National Women's Party of Turkey in 1972 which lasted till 1980 and the Women's Party (Turkey) set up in 2014. The number of women in Parliament had been increasing steadily with each election. In 1995 there were 13 women MPs. The number rose to 97 after the 2015 elections.

But in terms of women’s rights the rule of the AKP under Erdogan has seen an erosion in the rights that women enjoy. Reports suggest that under Erdog?an, domestic violence has doubled, female employment has gone down, and Erdog?an has himself made disparaging statements about how women measure up to men. The President has made moves to curb abortions and Caesarean sections. The “Ministry of Women” was changed to the “Ministry of Family and Social Politics” in line with the AKP agenda to return women to traditional roles as wives and mothers. The last major law protecting women in Turkey was passed in 1999, which was the Law on the Protection of the Family, geared toward protecting domestic violence victims. Since the AKP came to power no major laws for the protection of women have been passed, save for the domestic violence law which has yet to be properly enforced. Erdogan has lifted the ban on headscarfs which represented a victory for the conservative elements with secularists or ‘Kemalist’ women opposed to the move.

Candidate lists for the parliamentary elections on June 24, show a possible regression in women’s representation in Turkey’s Grand National Assembly in the next term. There are more women on candidate lists compared to previous elections, but fewer are in the upper ranks of the lists with a higher chance of getting elected. Out of 4,200 candidates from the seven parties entering the election, only 904 of them - or 21.5 percent of the candidates - are women. Only 49 of these women occupy the top places in their constituencies, which means only 5.4 percent of the women candidates are top of their lists. Based on the number of women in the upper ranks of the MP candidate lists, the eventual percentage elected is likely to be below the 14.7 percent of the current parliament. Erdogan’s own has placed only four women candidates at the top of the lists . In the November 2015 election 18 percent of the AK Parti’s candidates were women,

Erdogan’s increasingly autocratic behaviour and his belligerent outbursts have caused concern within Turkey and beyond. One article in 2017 described his demeanour as being that of a mob boss with an undercurrent of menace while recently ?Y? (Good) Party leader Meral Ak?ener said “Turkey is being ruled by a person who cannot control the words they utter.”

Erdogan had accused foreign powers of trying to “weaken” the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), after a French magazine portrayed Erdo?an as a “dictator. On one occasion he was reported to have publicly lauded Hitler’s Germany as an example of an effective Presidential system which is what last year’s referendum has sought to ensure. He accused Germany of “ Nazi Practices” after two of his Ministers were not allowed to attend rallies supporting him and Germany came in for criticism for allowing the HDP to hold rallies but not letting his ministers speak to his supporters. He had also called the Dutch “ Nazi remnants” when the Turkish Foreign Minister was stopped from landing in the Netherlands to address a rally.

Israel which in the past had been an ally also got a taste of Erdogan’s tongue when, after the recent border clashes in Gaza, he called the Israeli Prime Minister a “terrorist”. Relations with France have been tense with France increasingly criticising the Turkish military operation against the Kurdish YPG in northern Syria and hosting, at Presidential level, a Syrian delegation including the YPG and its political arm, the PYD, and giving assurances of French support to help them stabilise northern Syria against Islamic State.

But his real anger has been directed at the United States. The initial reason-the US refusal to extradite Fethullah Gulen. Then after the US announced that it was raising a new border force in Syria of 30,000 personnel in support of the YPG and other militias Erdogan threatened attacks on U.S. special operations forces working with the militias saying “Don’t force us to bury in the ground those who are with terrorists.” He said the force would be strangled before it was even born.

The America and Turkish approach to Syria has also been different. While both want Bashar al Assad removed, Erdogan, who has always been close to the Muslim Brotherhood-one reason for his siding with Qatar against the Saudi Arabian engineered boycott of that state- has sought Assad’s ouster through Syrian rebel factions aligned to the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamic groups paying less attention to the fight against Islamic State which has been an American priority.

On Iraq also Erdogan’s belligerence was directed at America after the US administration said any Turkish operation inside Iraq should be with the approval of the Iraqi Government. Erdogan’s response was that if terrorists took refuge inside Iraqi territory and the Iraqis failed to deal with them, Turkish forces would cross the border and Turkey did not need anyone’s approval.

Freedom of expression has been a major casualty of Erdogan’s rule. Some of those behind bars are foreign journalists, and others are high profile Turkish writers. In the post aborted coup era journalists can now get apprehended for articles that were published perfectly legally some years ago, but that are now, on dubious grounds, called ‘terrorist propaganda’. Those arrested and sentenced included Akin Atalay, the Cumhuriyet’s chairman who said after his release that there was no justice or judicial system in Turkey now. The latest victims were Murat Sabuncu the editor-in-chief of Turkey’s opposition Cumhuriyet newspaper and over a dozen of his colleagues who were sentenced to prison terms on terrorism charges and blamed for supporting Gulen.

The opposition Republican People’s Party’s (CHP) had brought out a report on “Turkey’s Internet Access Problem,”. Nearly 100,000 web pages were said to have been banned. Most of the bans were applied without proper investigations being conducted and without any testimonies being taken.

Will Erdogan win and achieve his ambition of being Turkey’s supreme leader subject to no checks and balances? Possibly if the government controlled media is to be taken at face value. Could there be an upset like in Malaysia? Also possible since there is an undercurrent of resentment against Erdogan that fails to find mention in the media but is evident to close observers of Turkish sentiment. Voter turnout will be a major factor in determining the victor and with an overwhelmingly young population it is their perceptions of what Turkey should be that might determine the outcome of the elections.