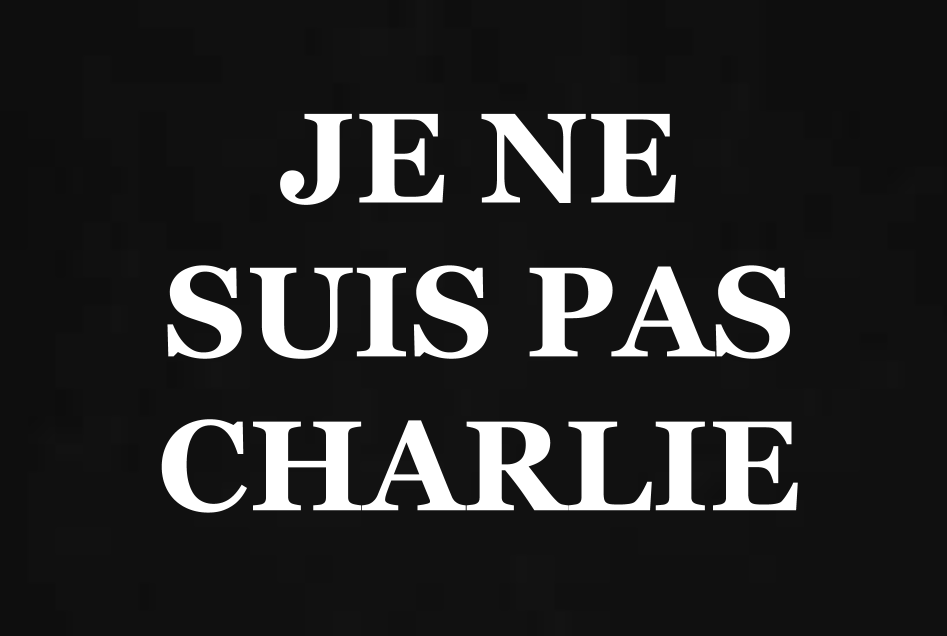

Why I am Not Charlie

I am not Charlie

NEW DELHI: Free speech. These two words are appearing with increasing ferocity as the world reels from shock following the attack on French magazine Charlie Hebdo that killed 12 people in Paris on Wednesday, including the editor and celebrated cartoonists.

“The magazine has every right to publish what it wants,” say the overnight champions of free speech. “So what if they depicted the Prophet in their caricatures? They didn’t limit themselves to Islam.” The magazine’s editors had in fact defended their decision to publish the cartoons that are being linked to this attack along the same lines. “We do caricatures of everyone, and above all every week, and when we do it with the Prophet, it's called provocation."

Charlie Hedbo’s website homepage has been replaced with the following:

The hashtag #JeSuisCharlie is trending across social media. Most of the posts are linked to the overarching value of “free speech.”

But was the attack really an attack on free speech?

Amongst the din of ‘free speech’, the context of the attack is being obfuscated. The context is specifically of an impoverished Muslim minority in white-majority Europe.

To give a parallel, if a publication based in the United States with an exclusively white staff published a cartoon depicting a white middle class American as a lazy, fat gorilla, it could be a case for free speech, but if the magazine were to publish a caricature of an African-American man as the same lazy, fat gorrilla -- would it not qualify as hate speech?

As someone put it, let’s not use the rouse of free speech to defend hate and bigotry.

A brief look at the caricatures published in Charlie Hebdo may elucidate this point further.

The last cartoon depicts the women kidnapped by Boko Haram as welfare queens.

In short, the magazine’s intention is to provoke. However, that provocation is not equal in its intent. The target is very clear: France’s Muslim immigrant community.

This is not to suggest that the attack should not be condemned. Nor is to state that journalists are legitimate targets. Nor do we in any way intend to suggest that publishing something -- whether a cartoon or article -- is the ground for such an attack.

What we are suggesting is that we need to look beyond the rouse of “free speech” and understand the context and implications of this attack.

As an article by Asghar Bukhari in the Medium points out, “The Muslims today are a demonized underclass in France. A people vilified and attacked by the power structures. A poor people with little or no power and these vile cartoons made their lives worse and heightened the racist prejudice against them.

Even white liberals have acted in the most prejudiced way. It was as if white people had a right to offend Muslims and Muslims had no right to be offended?”

The same article goes on to explain the context further. “This anger sweeping the Muslim world, is solidifying in the consciousness of millions, re-enforced by daily bombings, kidnappings and of course wars that the West has initiated and engaged in. These policies have lead to many Muslims abandoning the belief that they could bring any change peacefully?—?cue the rise of men taking up arms.”

Again, this is not meant to condone the incident. However, unless we address this perpetuation of polarisation -- attacks like the attack on Charlie Hebdo will only increase in severity and scope.

Because of this, Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie. And I am not the only one.

Hence, it is not a “with us” or “against us” matter. It never is. As Richard Seymour wrote in Jacobin Magazine:

“Given the scale of the ongoing anti-Muslim backlash in France, the big and frightening anti-Muslim movements in Germany, and the constant anti-Muslim scares in the UK, and given the ideological purposes to which this atrocity will be put, it is essential to get this right.’

In conclusion, this is not about free speech. It is about much, much more than that.