Increasing Disquiet in Tunisia

Messy democracy

Tunisia had been one of the only sustained success stories of the Arab Spring Widespread and continuing demonstrations, spearheaded by the youth but involving labour, lawyers and other segments of civil society had finally led to the ouster of strongman Zine Al Abdine in 2014. A new constitution had been framed providing for civil and women’s rights while limiting the power of the armed forces.

A messy democracy ensued but there was a triumphant mood as a number of new media channels and newspapers appeared on the scene; and political parties and civil society groups emerged. There was the hope that with regular elections and a democratic setup, the peoples’ aspirations stifled under dictatorship would be met.

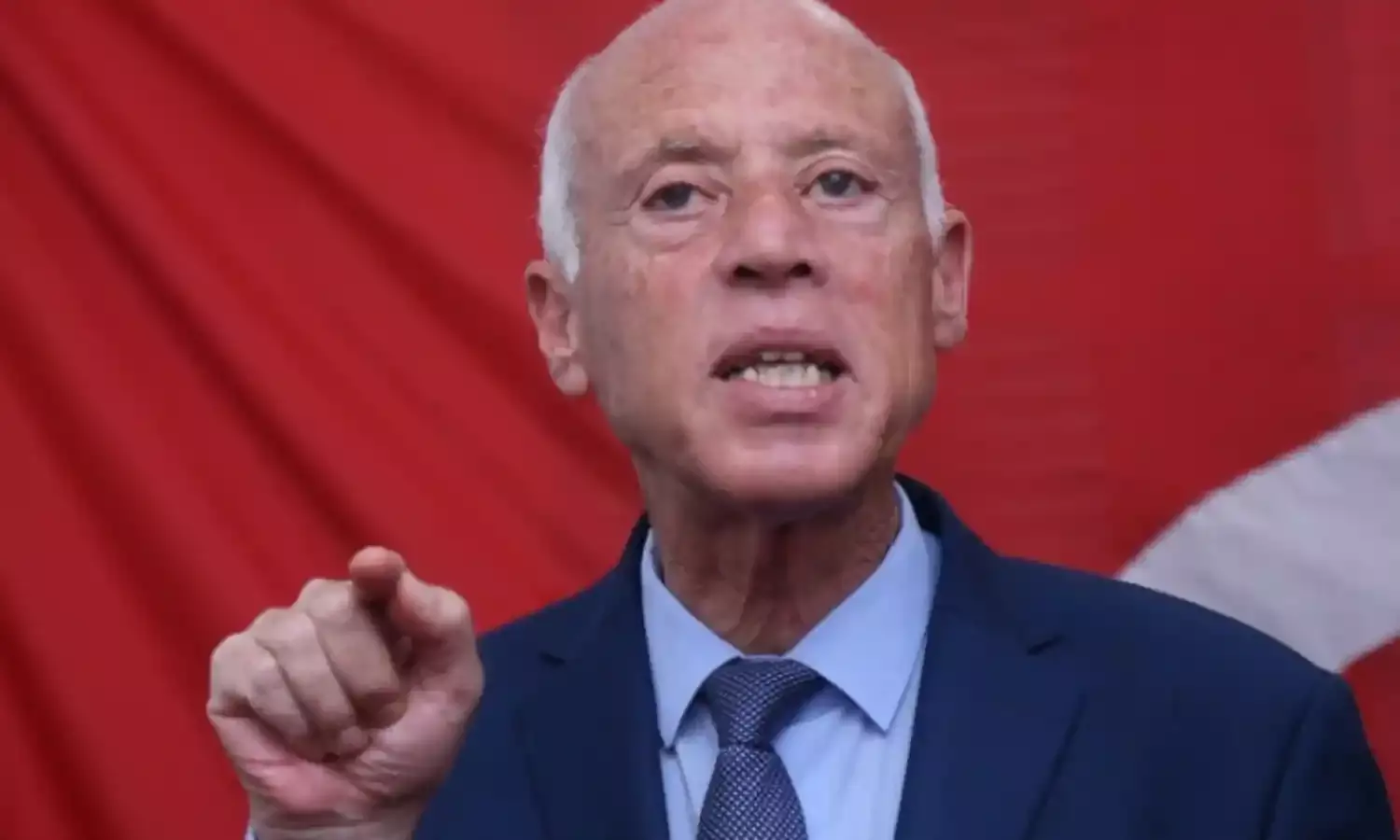

In the last presidential elections in 2019, the people fed.up of established non performing political leaders had given Kais Saied – a non party jurist and former university professor -- a landslide victory. He had promised that he would establish "a true democracy in which the people are truly sovereign" and root out corruption.

The people supported him but of late there were growing misgivings that Saied’s actions since July 2021 were geared towards another end. Commentators had begun to suggest that what Kais Saied had been doing for the past months showed little respect for the existing constitution and he was paving the way for an autocracy and one man rule.

On July 25 2021, the President sacked the Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi, who had taken office in July 2020; suspended parliament; and assumed executive authority citing emergency provisions in the Constitution. He said his actions were necessary to address the political paralysis, economic stagnation and a poor response to the coronavirus pandemic. on September 22, 2021 rules incorporated in the official gazette that would let him issue "legislative texts" by decree, appoint the Cabinet and set its policy direction and basic decisions without interference.

Only the preamble to the existing constitution and any clauses that did not contradict the executive and legislative powers he had seized would remain in force. He promised to uphold rights and not become a dictator but Tunisia had been left without a Prime Minister despite demands from the people and politicians. Saied had also said that he intended to change the constitution and would appoint a committee to help draft amendments to the 2014 constitution and would hold a referendum .

And the fresh elections would be held in December. But as people wondered when he would cede total control the President announced that the state of emergency would continue till the end of 2022 and then elections would be held.

While there was initial approval of the President’s September 2021 moves, his use of the military to quell protests had let to many of his supporters drifting away. Jailing of opponenets was increasing. The courts under the new set up had sentenced former president Moncef Marzouki to four years in prison in December 2021. Human Rights Watch had issued a report that a wave of arrests since July 2021 included Former Justice Minister Nourredine Bhiri who was arrested on January 31 by plainclothes police officers who forced him into their vehicle and held him in unidentified locations without any arrest warrant or formal charges.

The President’s most recent moves had provided ammunition to those who suspected his motives and with each decision there had been an increase in public protests.

For quite some time the President had been at odds with the judiciary accusing the Supreme Judicial Council’s members of taking “billions' ' in bribes and delaying politically sensitive investigations. He specifically referred to the members blocking investigations into the 2013 assassinations of leftist political figures Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi.

He had also accused the Islamist Ennahdha party, which played a central role in Tunisian politics for the decade since the revolution of infiltrating the Council. He had repeatedly stated that the judiciary had to realise that it was not the state but an instrument of the state. He had recently dissolved the existing Supreme Judicial Council, a constitutional body. Its building had been locked by the police to prevent staff from entering.

A decree was issued establishing a new provisional Supreme Judiciary Council. The decree gave the President the power of selection, appointment, promotion, and transfer of judges and, in certain circumstances, to act as a disciplinary body in charge of removals. None of the members of the new council would be elected but chosen by the President.

The ousted Supreme Judicial Council head Youssef Bouzakher had said he had been informed by the Ministry of Interior of “serious threats” against him. Tunisia’s Judges Association called for a two-day strike of all courts in the country.

Anas Hamadi, president of the Association of Tunisian Judges, told the media that Saied’s action was illegal and he had abolished the “legitimate council” and “installed a new council obedient to the executive power.

The Young Magistrates Association said the President had undertaken a political purge of the judiciary. Ennahdha leader Rached Ghannouchi, the speaker of the suspended parliament, said Parliament rejected Saied’s decision to dissolve the top judicial council and expressed his support for the judges. Three other parties, Attayar, Joumhouri and Ettakatol, had also issued a joint statement rejecting the President’s action.

Demonstrations had broken out with people waving Tunisian flags, and chanting “Shut down the coup… take your hands off the judiciary”. In the capital Tunis a march was organised by the country’s biggest political party Ennahda and a separate civil society organization. While the protests were covered by the media the journalists' union was reported to have commented that state television had stopped featuring political parties in discussion programmes. But in his latest move the President had removed the temporary head of national radio, Chokri Cheniti, who had been appointed in September 2021. No replacement was named.

There had been considerable criticism of President Kais Saied’s moves against the judiciary. While the USA had been supportive of him after his election, the US State Department had said that it was essential that the government of Tunisia held to its commitments to respect the independence of the judiciary, as stipulated in the country’s existing constitution. U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretaries Karen Sasahara and Christopher Le Mon had met with Tunisian civil society representatives for discussions about the recent developments.

The envoys of the Group of Seven nations and the European Union said they were “deeply concerned” about Saied’s move against the council while High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet called Kais Saied’s action a big step in the wrong direction. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) Tweeted that the decree placed all power in the hands of the President and effectively ended any judicial independence in Tunisia.

The President’s actions were likely to worsen Tunisia’s already dismal economic situation. A decree had been issued that Tunisia would issue a national subscription to cover part of the state budget for the year 2022. With regard to international support the government was seeking an International Monetary Fund (IMF) rescue package, which the finance minister hoped to secure by April 2022 and which would facilitate the flow of bilateral aid. But people were concerned that a deal with the IMF could worsen the situation.

Normal IMF conditions like increased taxation, austerity, reduction in subsidies would adversely affect living standards. But most donors were sceptical of any agreement being finalized before the summer and the delay could lead to serious problems including pressure on the currency, payment of state salaries and the import of some staple subsidised goods. Such a crisis could also impact on the President’s plans to introduce a new Constitution.

But more importantly the growing frustration and anger being manifested on the streets could escalate and lead to the kind of riots similar to those on January 14, the anniversary of the ousting of Tunisia’s former President Ben Ali. Tunisians had earlier witnessed what people power could do—oust a dictator and elect an unknown.

Where will Tunisia go now? There is little evidence that the President is going to undo what he has done. Will Elections take place to Parliament soon? It looks unlikely unless the President has a change of heart. Will there be the kind of outpouring of protests that marked the Arab Spring in Tunisia?

It is too soon to tell—if the President continues to use the military to enforce his will and there are clashes on the streets the mood in the military might change and without its support the President, who is losing his former charisma, might find himself with no supporters. Tunisians can only hope that wisdom prevails and the people become the priority.