Families of 'Desaparecidos' Search for Missing Relatives

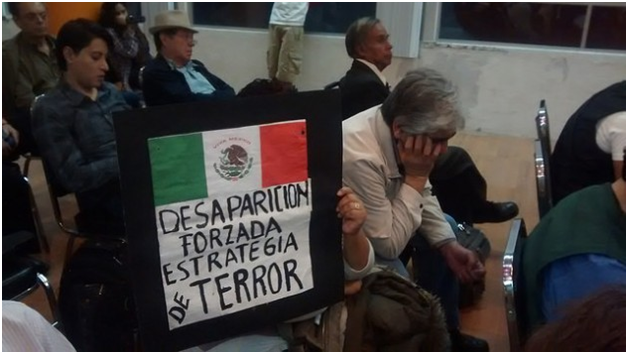

'Forced disappearance, a strategy of terror' reads a sign with the Mexican flag, held by a family me

MEXICO CITY (IPS): Carlos Trujillo refuses to give up, after years of tirelessly searching hospitals, morgues, prisons, cemeteries and clandestine graves in Mexico, looking for his four missing brothers.

The local shopkeeper has left no stone unturned and no clue unfollowed since his brothers Jesús, Raúl, Luís and Gustavo Trujillo vanished – the first two on Aug. 28, 2008 in the southern state of Guerrero and the last two on Sep. 22, 2010 on a highway that joins the southern states of Puebla and Veracruz.

“The case has gone nowhere; four agents were assigned to it, but there’s still nothing concrete, so I’m forging ahead and I won’t stop until I find them,” Trujillo told IPS.

On Feb. 18, Trujillo and other relatives of “desaparecidos” or victims of enforced disappearance founded the group Familiares en Búsqueda María Herrera – named after his mother – as part of the growing efforts by tormented family members to secure institutional support for the investigations they themselves carry out.

“We want to create a network of organisations of victims’ families,” the activist explained. “One of the priorities is to strengthen links and networking, to ensure clarity in the search process, and to share tools. The aim is for the families themselves to carry the investigations forward.”

The group is investigating the disappearance of 18 people. Prior to the creation of the organisation, some of the members found six people alive, in the last two years.

With determination and courage, the family members visit morgues, police stations, prisons, courtrooms, cemeteries and mass graves, trying to find their lost loved ones, or at least some clue that could lead them in the right direction.

The group grew out of the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity, which in 2011 brought together the families of victims of the wave of violence in Mexico, and held peace caravans throughout the country and even parts of the United States, where the movement protested that country’s anti-drug policy.

Enforced disappearance became a widespread phenomenon since the government of conservative Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) declared the “war on drug trafficking.” His successor, the conservative Enrique Peña Nieto, has not resolved the problem, which has become one of the worst tragedies in Latin America’s recent history.

But the phenomenon has only drawn international attention since the disappearance of 43 students of the Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college, which exposed a cocktail of complicity and corruption between the police and the mayor of the town of Iguala and a violent drug cartel operating in Guerrero.

Thursday marks the five month anniversary of their disappearance.

The families have not stopped their indefatigable search for the students, even though the attorney general’s office announced a month ago that they were killed by the organised crime group “Guerreros Unidos” and their bodies were burnt.

The humanitarian crisis prompted the United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances to demand on Feb. 13that Mexico pass specific laws to combat the problem, create a registry of victims, carry out proper investigations, and provide justice and reparations to the victims’ families.

Mexico’s office on human rights, crime prevention and community service has reported that in this country of 120 million people, 23,271 people went missing between 2007 and October 2014. However, the office does not specifically indicate how many of these people were victims of enforced disappearance, as opposed to simply missing. Human rights organisations put the figure at 22,600 for that period.

Most enforced disappearances are blamed on drug cartels, which dispute smuggling routes to the lucrative U.S. market, in some cases with the participation of corrupt local or national police. The victims are mainly men from different socioeconomic strata, between the ages of 20 and 36.

“Each one of us started with our own particular case,” Diana García, whose son was disappeared, told IPS. “We didn’t understand what disappearance was; we had to learn. We didn’t know we had a right to demand things. The search started off with problems, no one knew how to work collectively, and we gradually came up with how to do things.”

Her son, Daniel Cantú, disappeared on Feb. 21, 2007 in the city of Ramos Arizpe in the northern state of Coahuila.

García, who has two other children and belongs to the group Fuerzas Unidas por Nuestros Desaparecidos en Coahuila, is convinced that only by working together can people exert enough pressure on the government to get it to search for their missing loved ones.

With the support of the Centro Diocesano para los Derechos Humanos Fray Juan de Larios, a church-based human rights organisation, a group of family members of victims came together and founded Fuerzas Unidas in 2009, which is searching for a total of 344 people.

The organisation successfully advocated the creation of a new local law on the declaration of absence of persons due to disappearance, in effect since May 2014, as well as the classification of enforced disappearance as a specific crime in the state of Coahuila.

Other groups have emerged, such as Ciencia Forense Ciudadana (Citizen Forensic Science), founded in September to create a forensic and DNA database.

“The initiative is aimed at a massive identification drive,” one of the founders of the organisation, Sara López, told IPS. “To do this we need a registry of victims of disappearance, a genetic database, and a databank for what has been found in clandestine graves.”

The project plans to cover 450 families affected by enforced disappearance and to reach 1,500 DNA samples. So far it has gathered 550, and it has representatives – victims’ relatives – in 10 of the country’s 33 states.

On Feb. 16, Ciencia Forense identified the remains of Brenda González, who went missing on Jul. 31, 2011 in Santa Catarina, in the northern state of Nuevo León, with the support of an independent forensic investigation carried out by the Peruvian Forensic Anthropology Team.

“With the organisation that we just created, we will also try to provide a broad assessment of the question of enforced disappearances,” Trujillo said.

Human rights organisations say that until the case of the missing Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college students erupted, the authorities did very little to combat the phenomenon, and failed to adopt measures to comply with sentences handed down by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights.

The plight of the families is described in the song “Desaparecido” by French-Spanish singer-songwriter Manu Chao, dedicated to the thousands of victims of enforced disappearance in Latin America and their families: “I carry in my body a pain that doesn’t let me breathe, I carry in my body a doom that forces me to keep moving.”

And their lives are put on hold while they visit registries, fill out paperwork, lobby, take innumerable risks, and rack up expenses as they search for their loved ones and other desaparecidos.

“For now, I’m not interested in justice or reparations,” said García. “What I want is to know the truth, what happened, where he is. I’m looking for him alive but I know that in the context we’re living in there may be a different outcome. It’ll probably take me many years and I am desperate, but I continue the struggle.”

Her organisation, Fuerzas Unidas, drew up a plan that includes the analysis of crime maps, a genetic registry, awareness-raising campaigns, and proposed measures to hold those responsible for botched investigations accountable.

“The families are more familiar with the situation than anyone else, they know what has to be done. The problem is that we are overwhelmed by the magnitude of the phenomenon in Mexico,” said López.

(INTER PRESS SERVICE)