The Unsung Sheroes of 2014

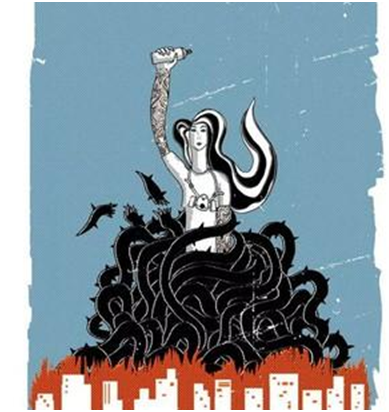

Girl Power

Delhi (Women’s Feature Service) - With an eventful Year 2014 drawing to a close, it‘s time to honour the women who have created a stir, inspired change and given a reason to hope for a better future. No, they are not your usual newsmakers … actors, business giants, sportspersons, who make it to the ‘Women of the Year’ lists. These are ordinary women whose extraordinary acts have made a difference to the lives of real people. Meet an astute tribal feminist in Bengal, who instinctively understands what women want and motivates them to achieve it; a group of amazing women doctors, who gave their all to save lives during the devastating Srinagar floods; feisty Rajasthani women, who are defying conservative social norms to join professions that are seen as male bastions; a brave journalist, who shares her story of childhood abuse as an appeal for people to recognise and save their children from becoming hapless victims to this heinous crime; the Muslim girls of Mumbra, who are playing ball to build a just and equal society that celebrates difference and interdependence; and finally, a female immunisation worker, who played her part in helping India get polio free.

The Santhal Feminist

Kanaklata Murmu, a Santhal tribal, is an unusual a community leader in an unlikely setting. Not many Santhal women, living in the remote village of Kumari in Purulia’s Manbazar II block in Bengal, have been able to perceive the hypocrisies of their society with the clarity that this mother of two has. Kanaklata instinctively understands the feminist principle of the right to mobility and points out that keeping a woman tied to her home is like cutting off the wings of a bird.

“Everything is based on mobility, one’s whole development as a human being is based on one’s capacity to move from place to place. But women here are constantly facing restrictions, whether in their parents' homes or their husbands,” she observes.

She became a force to reckon with ever since she joined the Society For Creating Awareness Among the Deprived People of Their Rights in Purulia district in 2006. Having lived in Kumari all her life, she understands well the realities that women experience. She says, “Men drink, beat their wives and sometimes throw them out of their houses. We slowly realised that the food we get in our husband's homes does not come for free. Every woman works hard to keep her family going, and she too has rights to live in her husband’s homes as an equal.”

Today, Kanaklata has not only ensured that women have a voice in their own home but she has been able to get drinking water for the people in her village, work under the MGNREGA, and pensions for several elderly widows. The one thing this feisty woman regrets is her lack of education, “I am a Class Eight dropout. If had more education, I would have been able to do so much more for my people.” But how many educated women have achieved even half of what Kanaklata Murmu has been able to do?

- Text by Pamela Philipose

***

Rajasthani Women Break The Glass Ceiling

The year 2014 was monumental for women in the desert state. They defied conservative social norms to join the state roadways as bus conductors and the fire service as brave heart fighters…

These days, if you happen to travel by a state roadways bus in Rajasthan, chances are that a woman will come up to you and say: ‘Aapko kahan jaana hai (Where do you want to go)?’ Clad in a salwar-kameez and jacket, a blue coloured whistle hanging from her neck and a ticketing machine in her hand, Manju Prajapati is one of the 14 female recruits from Nagaur depot who has joined Rajasthan Roadways in March 2014.

For the first time this year, the Rajasthan State Roadways Corporation opened up the job of the bus conductor to women. “It is almost a 12-hour duty for us,” informs Manju, who got in after finishing her first-year college exams, adding, “It is quite an exhausting run. The absence of basic facilities, like washrooms at most bus terminals, particularly in the smaller towns, makes life really problematic for us.”

What’s the greatest challenge they have faced on duty till date? Says a female conductor from the Sikar zone, “Blowing the whistle! In the feudal set-up of Rajasthan, imagine a woman blowing the whistle to start and stop the bus in the presence of the village elders. It will take time for people to get adjusted to our new role.”

From steering the bus to saving lives, women like Sita Khatik and her other bold and fearless female colleagues in the fire service are inspiring more women to follow in their footsteps. “Dousing the hungry flames is certainly not an easy task. It’s a test of one’s physical strength as well as courage and agility. But if one is determined, one can overcome any risks,” remarks Sita.

Most of Sita’s female colleagues hail from the small towns and villages. For them, it was not easy to opt for a profession that is traditionally seen as a male bastion. The selection process was certainly no cakewalk either. Out of over 1,000 applicants, just 155 managed to clear the Fireman Elementary Course training programme.

Nirma, who hails from a village in Sikar, shares, “It is essential to keep oneself fighting fit. We have been intensively trained to use the water hoses, carry the scale ladder and rescue and evacuate people to safety from buildings under fire.” Sunita Devi, who joined the Jaipur fire station along with Sita, signs off, “It gives us a sense of great satisfaction if we are able to save lives and people’s homes and belongings.”

- Text by Abha Sharma

***

They Saved Lives In Food-Hit Srinagar

On the morning of September 6, 2014, when Kashmir woke up to the biggest flood of the century, Dr Shahnaaz Teing, who heads the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at Lal Ded, found herself stuck with hundreds of patients at the 700 bed facility. The water level was already 15 feet high, submerging the ground floor and leaving the canteen, electricity supply room and blood bank defunct. With the entire hospital plunged in darkness, there was mayhem everywhere.

Eighteen staff members and 300 patients and 400 attendants were trapped together. While the adults were hungry, the infants on ventilators and incubators, which run on electricity, were freezing in the cold and gasping for oxygen. Even as Dr Teing performed surgeries by candlelight, she came up with some out-of-the-box solutions to keep everyone alive. Dextrose saline water used to treat dehydration was distributed for drinking among patients and their attendants. A few doctors put themselves on IV drip to remain active. “Can you imagine a doctor using her own handkerchief or patient’s headscarf for dressing? I did it that night,” she states. Six healthy babies were born – four normal and two Lower Segment Caesareans.

Meanwhile, at the GB Pant Children’s Hospital in the Valley, Dr Iram Ali, a senior resident, provided much-needed assurance and succour. When the incubators stopped functioning, she taught mothers of the sick neonates the technique of Kangaroo Mother Care and demonstrated how they could keep their infants warm by holding them tightly to their bodies. “We simply had to find alternatives,” she recalls.

Dr Nazeera Farooq, too, single-handedly operated upon 75 pregnant women that landed up in her private hospital in Srinagar in those trying days. Her Safa Marwa Hospital gave free medical service to patients and provided food and shelter to their attendants. “As there was no power, I used my diesel generator to conduct surgeries. When the diesel ran out, I operated in torchlight,” she shares.

Surely, when the times get tough, tough women like this extraordinary trio, get going.

- Text by Shazia Yousuf

****

Mumbra’s Muslim Girls Play Ball

They started off as a secret sports club. What brought them together was their shared love for football, a game they couldn’t dream of playing. After all, how could young girls, who weren’t even allowed to step out without the ‘hijab’ (veil), run around kicking ball in an open field? But they did it all for their passion for the sport. Three years back, Sabah Khan, Salma Ansari, Sabah Parveen, Aquila, Saadia and 40 other girls got out of their homes in Mumbra, a small town 40 kilometres from Mumbai, Maharashtra, to play football. Today, this group that calls itself Parcham, inspired by Asrar ul Haq Majaz, an Urdu poet, who saw women as crusaders with an inherent quality to revolt against exploitation and injustice, has truly lived up to its name.

Sabah Khan, the captain of this unique all-girls team, says, “Most of us hail from families that struggle to make ends meet. We can never really spare time for fun and games. We study, chip in at home or work.” Though they play every Sunday, many have to lie to their families even now. Says Saadia Bano (name changed), “There are many like me who cannot yet be completely honest with all their family members. We don’t want to make them unhappy nor do we want our freedom curtailed. This way we all get what we want.”

Through sports, Parcham strives to build a just and equal society that is respectful of diversity and celebrates difference and interdependence. Simran, 15, the youngest member of the team, is a Sikh. “We have so many misconceptions about other religions. But perceptions change when we meet and interact. Being in Parcham, I am learning about gender, equality, justice… Watch out, I am a feminist in the making!” she says.

- Text by Kamayani Bali-Mahabal

****

The Silence On Child Sexual Abuse

Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) is shrouded in deafening silence in our society and the widespread notion that such abuse can be perpetrated only through touch hampers even a basic understanding of CSA. A central characteristic of any abuse is the dominant position of an adult that allows him or her to force or coerce a child into sexual activity.

Abuse brings with it a lot of fear, hurt and baggage; it alters forever a person’s sense of self and the way they deal with the world. I am 30 years old. I have worked as a full-time journalist for five years and continue to freelance. People who ask me about my profession are taken by surprise. With raised eyebrows, they ask: “How did you become a journalist? Doesn’t the profession require one to talk loudly and boldly? Do they take people like you too?” Termed as ‘meek’, ‘docile’, ‘inactive’, ‘silent’, ‘withdrawn’ and ‘non-social’, I have been haunted by these remarks, and have been questioned as to why I am such a misfit.

Probably, I would have dealt with this much earlier if only I had understood that I was a victim of CSA. It took me 15 years to come to terms with the suffering I had experienced and which I had completely buried within me. I was a victim of non-touch sexual abuse. I am not the first person to suffer from it, and I will not be the last.

However, I strongly feel that parents, teachers, friends, colleagues at the workplace and even legal and educational institutions need to be sensitive to the issue in order to create a space that would help such children identify theirs and others’ boundaries. This, in turn, would help them understand the violation of their boundaries. CSA should be rooted out of society before it devastates more lives. Children have the natural right to enjoy the wonderful things the world has to offer.

- Text by Senthalir S.

***

The real Star of the Pulse Polio Programme

Though UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador Amitabh Bachchan is the more celebrated face of the Pulse Polio Immunisation programme, it is women health workers like Sadaf Parveen, 27, from Malitola village, in Basti district of Uttar Pradesh, who have overcome barriers of illiteracy, religion and extreme weather to convince mothers to get their children ‘do boond zindagi ki’ (two drops of life), which have enabled India achieve polio-free status.

Parveen’s routine for the last seven years has revolved around going door-to-door educating expectant women and new mothers about the benefits of immunisation. The diligent young woman, who was forced to drop out of school due to a financial crisis in the family, says, “I am the youngest of nine siblings. I was only five when I lost my father in 1993. When it came to supporting my education my mother was helpless as it was a question of choosing between paying my fee and feeding us. In 2007, I noticed health workers on their usual round in my area. As I watched them something struck within me. I remembered my friend Shama who had polio. When all the children used to play she would sit quietly and watch us. She is now in Mumbai and is really proud of the work I am doing.”

For Parveen, her job as an immunisation worker has been a valuable learning experience, “Initially, people would slam the door on my face but I did not give up. They feared that polio drops would make their boys impotent. Nowadays, 98 per cent children are brought in on the very first day of the immunisation round.”

Thanks to the untiring efforts of the 25 lakh immunisation workers like Parveen, India is finally polio free.

Text by Tripti Nath

(Women's Feature Service)