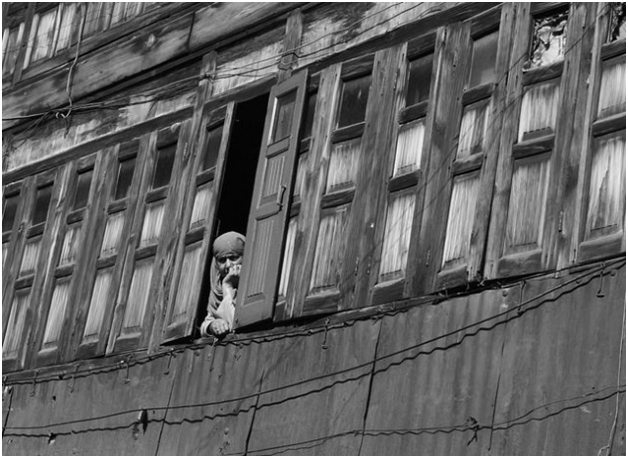

Dumped, Abandoned, Abused

Women in India's mental health institutions often face systematic abuse that includes detention,

MUMBAI (IPS) :Following the birth of her third child, Delhi-based entrepreneur Smita* found herself feeling “disconnected and depressed”, often for days at a stretch. “Much later I was told it was severe post-partum depression but at the time it wasn’t properly diagnosed,” she told IPS.

“My marriage was in trouble and after my symptoms showed no signs of going away, my husband was keen on a divorce, which I was resisting.”

After a therapy session, Smita was diagnosed as bi-polar, a mental disorder characterised by periods of elevated highs and lows. “No one suggested seeking a second opinion and my parents and husband stuck to that label.”

One day after she suffered a particularly severe panic attack, Smita found 10 policemen outside her door. “I was taken to a prominent mental hospital in Delhi where doctors sedated me without examination. When I surfaced after a week I found that my wallet and phone had been taken away.”

All pleas to speak to her husband and parents went unheeded.

It was the beginning of a nightmare that lasted nearly two months, much of it spent in solitary confinement. “The nurses were unkind and cruel. I remember one time when my entire body was hurting the nurse jabbed me with an injection without even checking what the problem was.”

On one occasion, when she stopped eating in protest after she was refused a phone call, she was dragged around the ward. “There were women there who told me they had been abused and molested by the staff.”

Not all the women languishing in these institutions even qualified as having mental health problems; some had simply been put there because they were having affairs, or were embroiled in property disputes with their families.

Days after she was discharged her husband filed for a divorce on the grounds that Smita was mentally unstable.

“I realised then that my husband was building up his case so he would get custody of the kids.”

Isolated and afraid, Smita did not find the strength or support to fight back. Her husband won full custody and left India with the children soon after. “My doctor says I am fine and I am not on any medication but I still carry the stigma. I have no access to my kids and I no longer trust my parents,” she told IPS.

Smita’s story points to the extent of violence women face inside mental health institutions in India. The scale was highlighted in a recent Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, ‘Treated Worse than Animals’, which said women often face systematic abuse that includes detention, neglect and violence.

Ratnaboli Ray, who has been active in the field of mental health rights in the state of West Bengal for nearly 20 years, says on average one in three women are admitted into such institutions for no reason at all. Ray is the founder of Anjali, a group that is active in three mental institutions in the state.

“Under the law all you need is a psychiatrist who is willing to certify someone as mentally ill for the person to be institutionalised,” Ray told IPS. “Many families use this as a ploy to deprive women of money, property or family life. Once they are inside those walls they become citizen-less, they lose their rights.“

Ray points to the story of Neeti who was in her early 20s when she was admitted because she said she heard voices. “When we met her she was close to 40 and fully recovered, but her family did not want her back because there were property interests involved.”

With the help of the NGO Anjali, Neeti fought for and won access to her share of family property and was able to leave the institution.

Those on the inside endure conditions that are inhumane.

“There is hardly any air or light. Unlike the male patients who are allowed some mobility within the premises, women are herded together like cattle,” says Ray. In many hospitals women are not given underclothes or sanitary pads.

Sexual abuse is rampant. “Because it is away from public space and there is an assumed lack of legitimacy in what they say, such complaints are nullified as they are ‘mad’,” adds Ray.

Unwanted pregnancies and forced abortions impact their mental or physical health. They languish for years, uncared for and unattended.

“One can’t help but notice the stark contrast between the male and female wards,” points out Vaishnavi Jaikumar, founder of The Banyan, an NGO that offers support services to the mentally ill in Chennai, capital of the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

“You will find wives and mothers coming to visit male patients with food and fresh sets of clothes, while the women’s wards are empty.” Experts also say discharge rates are much lower when it comes to women.

The indifference towards patients is evident not just in institutions, but also at the policy level, with mental health occupying a low rung on the ladder of India’s public health system.

According to a WHO report the government spends just 0.06 percent of its health budget on mental health. Health ministry figures claim that six to seven percent of Indians suffer from psychosocial disabilities, but there is just one psychiatrist for every 343,000 people.

That ratio falls even further for psychologists, with just one trained professional for every million people in India.

Furthermore, the country has just 43 state-run mental hospitals, representing a massive deficit for a population of 1.2 billion people. With the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) present in just 123 of India’s 650 districts, according to HRW, the forecast for those living with mental conditions is bleak.

“Behind that lack of priority is the story of how policymakers themselves stigmatise,” contends Ray. “The government itself thinks [the cause] is not worthy enough to invest money in. Unless mental health is mainstreamed with the public health system it will remain in a ghetto.”

Depression is twice as common in woman as compared to men and experts say that factors like poverty, gender discrimination and sexual violence make women far more vulnerable to mental health issues and subsequent ill-treatment in poorly run institutions.

Gopikumar of The Banyan advocates for creative solutions that are scientific and humane like Housing First in Canada, which reaches out to both the homeless and mentally ill. The Banyan is presently experimenting with community-based care models funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Canadian government.

“Our model looks at housing and inclusivity as a tool for community integration,” says Gopikumar. “The poorest in the world are people with disabilities and most of them are women. They are victims of poverty on account of both caste and gender discrimination and its time we open our eyes to the problem.”

*Name changed upon request

(INTER PRESS SERVICE)