The Original Diva Of Indian Cinema

Kanan Devi’s name may not ring a bell with the Gen X and Y but she has the distinction of being the first female super star of the over-100-years-old Hindi film industry. Working as a domestic help at the age of six to pay for her meals and staying in a notorious neighbourhood known for its brothels, she had no lineage, no godfather and no resources to draw up on. And yet, beginning her career as a child artiste at 10 she rose to become one of the biggest screen divas of her time, commanding a fee of Rs 100,000 for a song and Rs 500,000 for a film!

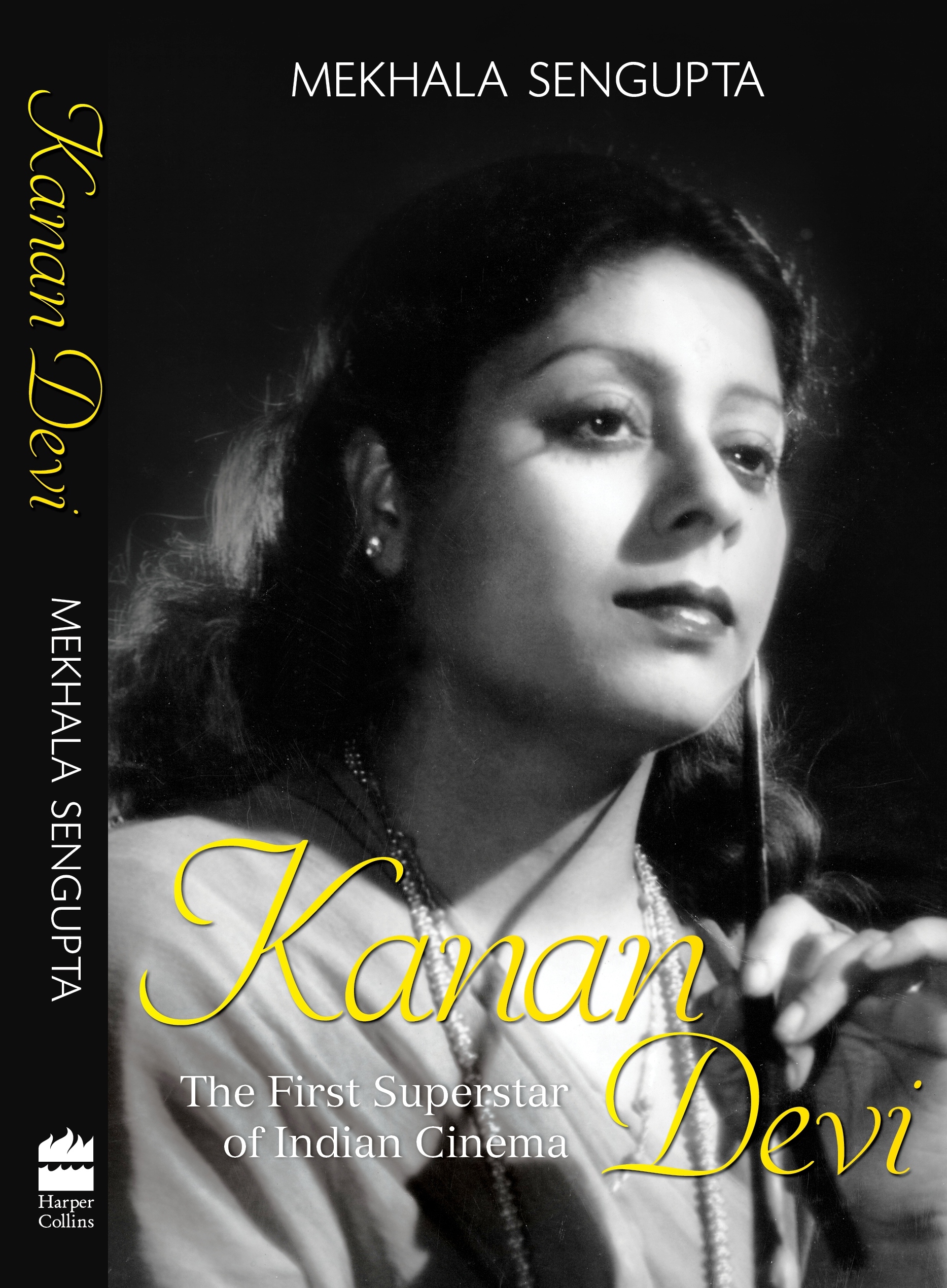

‘Kanan Devi: The First Superstar of Indian Cinema’, written by Mekhala Sengupta and published by Harper Collins, shares the incredible story of a fearless woman who fought stereotypes to live life on her own terms and rule an industry that is largely male-dominated now. An excerpt.

…Kanan had a brief personal meeting with Mahatma Gandhi. She had previously seen him from afar, when he had led the funeral procession for Chittaranjan Das in 1925. This time, Kanan came to the evening prayer meetings organized at Sodepur near Calcutta, over which he presided. She was eager to meet the Mahatma, so one of his associates, Satish Dasgupta, introduced her to the great leader with the words, ‘This is Kanan Devi, a well-known film star who wants to meet you and pay her respects.’ The Mahatma greeted Kanan with his characteristic smile and his famous line, ‘Sabko sammati de bhagawan.’ This tune kept ringing in her ears thereafter. On the same occasion, Kanan also met Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan or the Frontier Gandhi.

Kanan was aware of the Mahatma and other leaders encouraging people from all walks of life to join the freedom movement. She was especially aware of the importance he gave to women participating in the struggle. As more women became recording artistes and sang on the radio, they were initially encouraged by the Mahatma to sing for azadi and to join the movement. His call to women to get involved in the freedom struggle had far-reaching effects on their outlook.

Many women shed age-old prejudices. They showed no hesitation in leaving the boundaries of their protected homes and going to jail. They even broke their glass bangles, a sign of ill omen for married women, when they were told the bangles were made of Czechoslovakian glass. Women’s participation in the freedom struggle feminized nationalism and the nationalist struggle helped them try and liberate themselves from age-old traditions. Though Gandhi never challenged the traditional setup, he inspired women to carve out their own destinies within it, thereby changing its very essence. He encouraged them to be strong, even if seemingly weak, to protest against injustice. Along the way, they realized that they did not have to accept the norms of male-dominated politics. They evolved their own perspectives and formulated their own methods. Kanan came to know with some distress of the retraction of the Mahatma’s position and his later deposition on what he considered suitable for modern ladies in demeanour and apparel.

With the Indian subcontinent riven by political and religious turmoil, civil unrest had become rife in Calcutta. The Calcutta Riots of 1946, followed by the Partition of the country in 1947 led to a mass exodus from the city. Many prominent Calcutta minorities, which included the British, Europeans, Muslim Bengalis and Anglo-Indians, chose to leave the city they had made their home, some for generations.

All film work remained suspended during the period of communal turmoil and curfew between August 1946 and August 1947 and almost all studio owners, including Muralidhar of MP Productions, sustained huge losses. Kanan noticed with some alarm that Muralidhar had started consulting astrologers for their predictions on auspicious times for new projects. But none of this helped, and MP Productions was left with no option but to close down. Finally, with Partition, the East Bengal (which became East Pakistan and subsequently Bangladesh) market for Bengali films was practically destroyed.

The studio system prevalent in Calcutta was also breaking down, and was replaced by a much looser, distributor-oriented system, where there was greater reliance on the independent producer and more importance given to stars. With Calcutta losing a large segment of its commerce, industry, population and consumer demand, the film industry was affected. The Bombay studios were marching steadily ahead. With the studio system coming to an end, new independent production companies were being set up.

In the summer of 1947, Kanan made a trip overseas, to Europe and the US, and was in London when she heard Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘Tryst With Destiny’ speech. Kanan was honoured with the request to sing at the Indian High Commission in London on 15 August 1947 in the presence of the High Commissioner V.K. Krishna Menon. She sang the very appropriate ‘Amader jatra holo shuru’ (Our journey has now begun), a composition of the poet laureate Rabindranath Tagore.

Kanan paid a memorable visit to the Gramophone Company Limited at a reception hosted by them in London. While felicitating her, the managing director said it was their pleasure to honour their artiste Kanan Devi, the Indian melody queen. Kanan remembered vividly the many photo sessions, and the cakes and chocolates presented by Gramophone Company to ‘the Queen of Melody from India’.

On this trip, Kanan met with Hollywood legends such as Vivien Leigh, Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. Kanan was delighted to find that Vivien Leigh, whom she met for a long lunch, was an Indophile. Born in Darjeeling in Bengal, she had studied at the Loreto Covent there, before going to the Convent at Roehampton, then the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. When Kanan praised the English fruit pudding, made with delectable English summer peaches and also the strawberries and cream at the end of their lunch, Vivien quipped that it could not be compared with the excellence of Indian sweets and spoke at length about the taste and fragrance of the rice puddings, kheer, kulfi and ras malai that she had eaten when she lived in India.

With both Vivien and Kanan being talented, surreally beautiful women, both having reached the pinnacle of success in cinema, there was much they had in common. They talked about whether beauty could be considered an impediment to being taken seriously as an actress. Vivien Leigh, considered one of the world’s most beautiful women, said, ‘I only care about acting, I think beauty can be a great handicap, if you really want to look like the part you’re playing, which isn’t necessarily like you.’ Vivien explained that she played ‘as many different parts as possible’ in an attempt to learn her craft and to dispel prejudice about her abilities. She believed that comedy was more difficult to play because it required more precise timing and observed, ‘It’s easier to make people cry than to make them laugh.’

When Vivien asked her about the Indian film industry, replied that Indian cinema was still in its infancy compared to what she had seen so far in Europe and the US. Vivien Leigh then touched her hand and said, ‘You don’t have to be apologetic about this. India is ahead of everyone in its heritage in art, poetry and music. And where artistes are born with such a heritage, they cannot be suppressed by obstacles for long.’

As they exchanged pleasantries and technical notes, there seemed little evidence in their interaction then and later to suggest that Vivien suffered from the bipolar disorder she was diagnosed with in later years. Vivien Leigh remained special to Kanan because of her Indian connection.

(Excerpted from ‘Kanan Devi: The First Superstar of Indian Cinema’ by Mekhala Sengupta; Published by Harper Collins; Pp: 200; Price: Rs 350)

(Women's Feature Service)