Does India Care About Her Refugees?

AMIT SINGH

India is a home of millions of refugees and asylum seekers such as Tibetans, Afghani, Burmese, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankans and Africans. In the past, Antonio Guterres, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees(UNHCR) has applauded India’s refugees policy. In fact, Indian hospitality of welcoming foreigners is rooted in the ancient Indian tradition of ‘Athithi Devo Bhav’-- meaning ‘Guest is (our) God.’

However, the recent threat by the Indian government to deport 40000 Rohingya, including UNHCR recognised refugees, is not only a major breach of its international human rights obligation --- particularly the principle of non-refoulement --- but also, violates the old tradition of providing shelter to those seeking refuge on Indian shores.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, in his speech at the UN Human Rights Council’s 36th session in Geneva, had deplored the Indian decision to “carry out collective expulsions” and “return people to a place where they face persecution.” Indian response to the UN Commissioner has been typical and traditional. India -- just like its neighbours Thailand and Bangladesh (who are also not signatory of 1951 Refugee Convention) -- invoked its concern for “national security” to justify Rohingyas deportation. This has raised questions about India’s intention/willingness to protect human rights of its refugee populations within its jurisdiction.

This article is an attempt to analyse vulnerable situation of refugees against the backdrop of the ongoing Rohingya refugee crisis in India.

India has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention (which is legally binding principles for refugee protection) and, there is no specific domestic legal framework to protect the rights of refugees and asylum seekers in India. This has led to legal insecurity of refugees’ status and difficulty to access in terms of refugee rights. Due to the absence of specific laws related to refugees and asylum seekers, they are regulated under the Foreigners Act, 1946. However, the problem with this act is that it does not take special situation of refugees and refugees’ rights and treats refugees and asylum seekers with tourist, illegal immigrants, and economic immigrants alike.

The Indian legal framework has no uniform law to deal with its huge refugee population, and as such, it chooses to treat incoming refugees based on their national origin and political considerations, questioning the uniformity of rights and privileges granted to refugee communities as per the international human rights conventions and UN treaties. This results in unequal treatment towards refugee groups. This treatment is reflected in how refugees from China are well received compared to refugees from Myanmar in India.

Though recently, Indian Citizenship laws have been amended to accommodate specifically Hindu refugees from Pakistan and Bangladesh, ignoring other groups of refugees in need of protection. This step of the Indian government seems motivated by nationalist politics rather than humanitarian concern as many have pointed out.

Refugees from Myanmar and Somalia are often ignored by Indian policy makers, since these nationals do not serve a geo-political purpose, as refugees from China, nor do they share an ethnic or religious similarity as is the case of Hindu refugees from Pakistan and Bangladesh that serve ethno-nationalist purposes. There is hardly any concrete legal protection measures for Rohingya refugees in India even though they have been declared genuine refugees by the United Nations.

In the absence of a specific refugee policy, the Indian government takes administrative decisions on ad hoc basis keeping the national security in mind. However, ad hoc decision is more guided by the rhetoric of national security and foreign affairs -- as observed in Rohingya case where coinciding with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Myanmar, a threat of deportation has been issued to 40000 Rohingya refugees staying in India, in order to appease political leaders of Myanmar.

However, India is a signatory to various international treaties and conventions relating to universal human rights that applies to refugees such the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights. Thus, for India, it is imperative to exercise consistency in the application of refugee law and regional politics should be avoided in doing so. The current ad hoc arrangement dealing with refugees based on administrative, political and economic calculations, do not meet international standards of refugee protection. The principle relating to refugees in international law needs to be recognised in the Indian law — that of non-refoulement, which means non-expulsion or non-extradition to the place from which the refugee has fled as long as the compelling circumstances for fleeing persist.

States do not subscribe to an adaptive approach towards the sensitive human rights issues like refugees and minorities may find themselves increasingly isolated by the world community. Failing to adopt any asylum legislations does not free a country from its human rights obligations under treaties to which it is party or, indeed, under customary International law. States can not use national legislation to reduce their human rights obligation. Protection of refugees and asylum seekers shall be guided by the humanitarian concerns rather than matter of foreign affairs, national security and narrow politics of vote bank opportunism. If India is serious to claim is permanent position in the United Nations Security Council and wants to provide able leadership to the world, then it must set a good example in South Asia by providing a secure legal protection to its refugees and asylum seekers -- particularly to Rohingya refugees who are in dire need of protection.

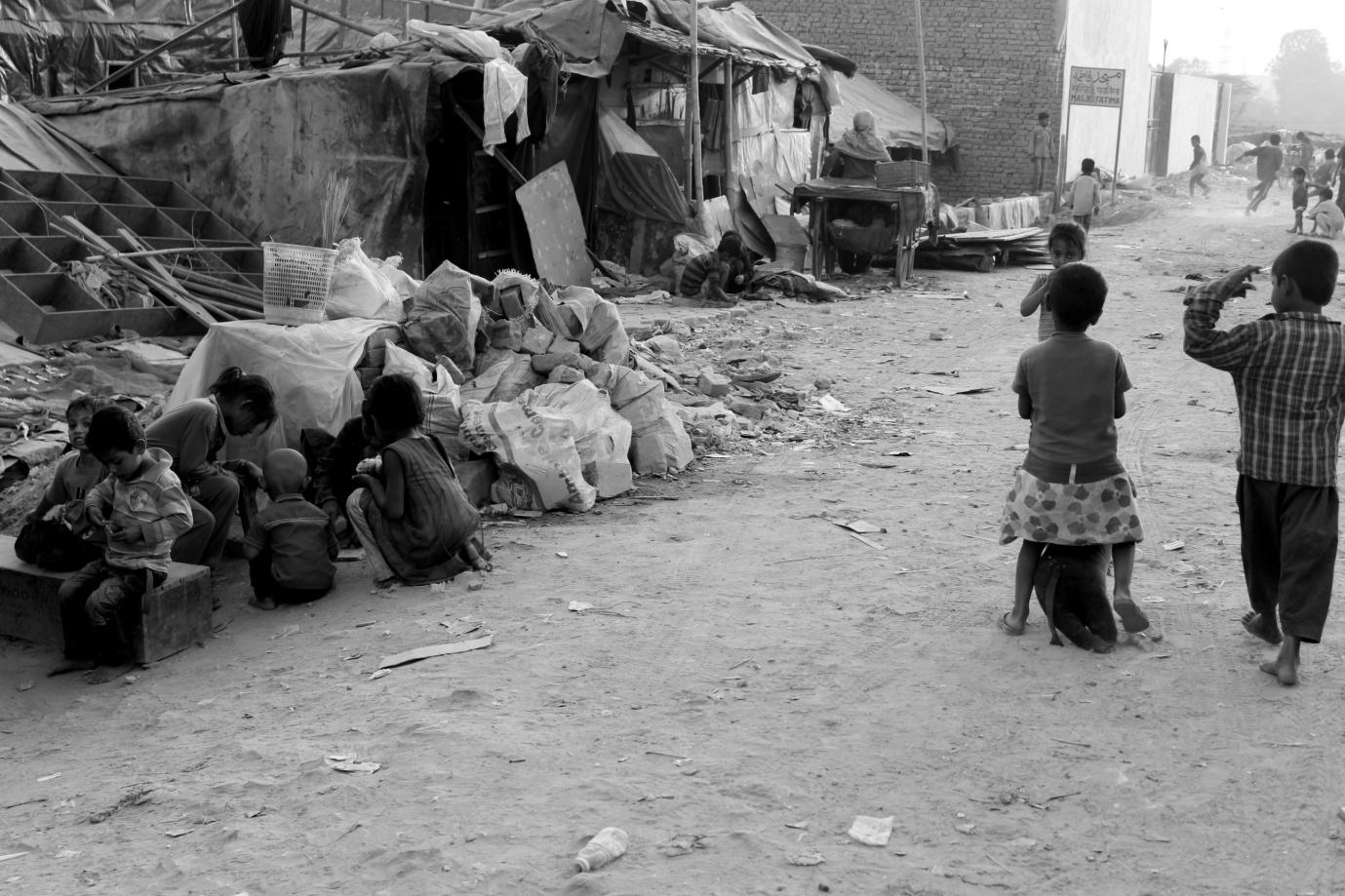

(Cover Photo: A Rohingya refugee camp in New Delhi. Photo by NAWAL ALI WATALI)