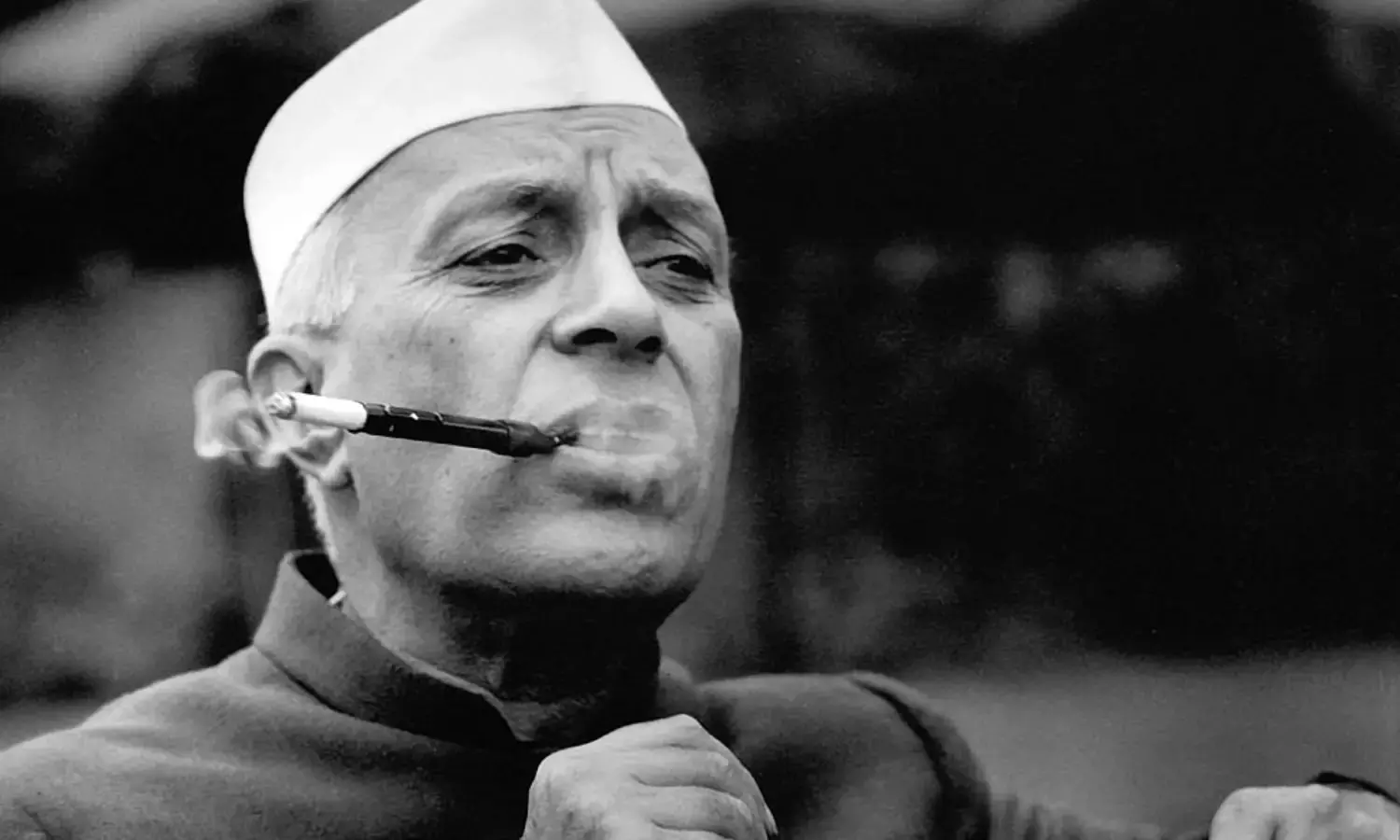

'Nehru Made a Great Speech, With Only Four Grammatical Errors'

Nehru and the literary giants of Allahabad

Allahabad, where Jawaharlal Nehru was born 129 years ago and with which he remained associated all his life, is much changed today, even in name.

Nehru’s association with the city remained life long. It was in its vicinity that, as a young party worker, he was ‘thrown into contact with India’s peasantry’, and so writes of it in his Autobiography: ‘A new picture of India seemed to rise before me, naked, starving, crushed, and utterly miserable. And their faith in us, casual visitors from the distant city, embarrassed me and filled me with a new responsibility that frightened me.’ After independence, he was the member of parliament from Phulpur nearby.

But this story is about Nehru’s literary association with Allahabad. It was in 1960 that Nehru decided to meet Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’, a poet who was a legend in his own lifetime. Nirala lived in Allahabad, as did his contemporaries Mahadevi Verma and Sumitranandan Pant, pillars all of the Chhayavad school of Hindi literature.

In 1960 Shreedhar Agnihotri (who retired in 2005 as director in the central government’s department of personnel and training) was a student of science at Allahabad University. Deeply interested in literature, he was also the publishing secretary of the Allahabad University Students’ Union. In this capacity he was often in touch with Nirala, and other literary figures in the city.

According to Agnihotri, Nirala, then in his sixties, lived frugally in a modest and ill kept house in Daraganj, with very few basic possessions and not much money. Whatever little he had, he was prone to give away to the people in need he came across. Says Agnihotri, ‘Nirala Ji hardly cared about his physical existence. As students, we would often visit him and try to do our bit, like arranging groceries, as he cooked for himself.’

Then the news spread: Nehru Ji was going to come to Allahabad and meet Nirala.

As Agnihotri recalls, this was big news and it was clear to him and other students that Nirala Ji was not in any position to receive Nehru. His house was not fit to receive any guest, let alone the prime minister of India. So, the students set about improving things. ‘We collected a few chairs, a rug for the charpai (string cot) where Nehru Ji would sit and some sweets (jalebi, burfi and ladoos) from a sweet shop in Daraganj.’

And this, according to Agnihotri who witnessed the whole scene, is what followed.

Nehru Ji arrived with accoutrements, including a battery of local Congressmen. This clearly displeased Nirala, for when Nehru entered the room Nirala Ji did not even get up to receive him. Nehru was duly seated upon the charpai but Nirala didn’t once look at him. He quite simply avoided all eye contact with Nehru, nor did he once address him.

What was worse, instead of looking Nehru in the eye, Nirala kept glancing at the rose adorning Nehru’s coat. And then he did something even more improbable.

You see, Nirala had written a collection of poems titled Kukurmutta, meaning mushrooms. He compared mushrooms with the working poor and wrote the rose, a much celebrated and decorative flower, as a symbol of the rich capitalist.

Nirala’s undue attention to the rose on Nehru’s coat was in this context. To prove it, he recited loudly a few lines from his poem, addressing the rose on Nehru’s coat. They went like this:

Ab, sun be, gulab / Bhool mat jo payi khushboo, rang o aab / Khoon chusa khaad ka tuney ashisht / Daal par itra raha hai capitalist!

Now, listen rose / Don’t forget the scent, colour and water you obtained / You sucked the blood of the manure coarsely / On the branch struts the capitalist!

Upon hearing these lines, Nehru got up and left. No words were exchanged between the two. ‘The fact that Nehru paid a personal visit to a poet’s home speaks volumes about Nehru, and about Nirala too. The way Nirala treated Nehru and the way Nehru tolerated Nirala was something that could have happened only in that age, between people of great stature.’

Another literary stalwart, a poet in Urdu who lived and taught English literature at Allahabad University was Raghupati Sahay, popularly known as Firaq Gorakhpuri. Firaq was known for his acid humour, cutting wit, uncompromising attitude and extremely high sense of self-worth. It is said that Nehru and Firaq were quite close and shared substantial mutual respect between themselves.

Firaq is famously reported to have said that only two and a half men in India knew English: one, Firaq and two, Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, with the remaining half represented by Nehru.

In another incident less well known, Nehru once addressed the students and faculty of Allahabad University in English. It was a rousing speech that earned much applause. Firaq rose immediately after Nehru to bring a motion of thanks. He began by saying, ‘Nehru made a great speech, and that too with only four grammatical errors.’

Well, such were the times. When we had individuals of Firaq’s stature who could point out mistakes in the prime minister’s speech and in his presence. When we had a prime minister who not only permitted criticism but appreciated and encouraged it.

Yet another anecdote from the Nehru and Firaq fable. It was narrated by Gauhar Raza, the well known contemporary poet, who has it from reliable sources that once, when Nehru was visiting Allahabad University, the students decided to throw a dinner in his honour. For this, a money collecting drive was duly launched. But Firaq, known to be a miser, refused to contribute. The dinner was still arranged, but Firaq did not attend. When Nehru reached the dining hall, the first thing he did was to start looking for Firaq. Unable to find him Nehru promptly enquired about him.

The organisers rushed people to find Firaq, who was found resting in his residential quarters. He was fervidly requested to come to the dining hall. Finally he relented. But the moment he entered the dining hall he addressed Nehru straight away, saying, ‘What is this? Now one has to pay for dinner in order to meet you.’

Nehru got the message and immediately announced that the dinner bill would be paid from his own pocket.

Now, things have changed much in Allahabad. The city’s celebrated literary spirit is long dead. And of course, it is no longer known as Allahabad but Prayagraj. It may be no more than mere coincidence that just a day after Nirala’s 57th death anniversary, on October 15, 2018, the name of Allahabad was changed to Prayagraj.