Media and People's Struggles, Then and Now

1789 and 1857 ' and Shaheen Bagh 2019

“In India one is always sitting on a volcano.”

—Lord Dalhousie, Governor-General of India, 1848

Shaheen Bagh now is a political idea. As ideas never die, it too has rolled into history. Shaheen Bagh of Delhi is perhaps the first recorded expression of public wrath in its continuity since the promulgation of the Citizenship Amendment Act.

This raises our inquisitiveness: how was public wrath reported in the media decades ago, particularly during the French Revolution of 1789 and the Sepoy Mutiny in Delhi’s theatre in 1857?

Both years 1789 and 1857 have become concepts in themselves. Shaheen Bagh 2019 too is a concept, a social-political approach. And ideas can never enter into the cold mortuary of history as they keep on evolving, like a live organism.

The media has always played the most dominant role in disseminating news of people’s wrath to inform and mobilise the masses and shape their opinions.

The year 1789 was the Age of Reason. The year 1857 was the Age of Nationalism. And the year 2019 – Shaheen Bagh – is perhaps the year of threats to citizenship.

Coming back to our quest of how Paris’s French Revolution and Delhi’s Sepoy Mutiny were reported in those days when there were no internet, fax, teleprinter or even telegram, we are amazed to find that the basic pattern of reporting did not much differ.

When Shaheen Bagh’s wrath exploded, the media had everything: video shooting or live telecast, sound recording, modern vehicles to transport the reporters and internet.

But in 1789, newspapers depended only on human couriers (journalists coming to the media office from the scenes of killings, riots on horseback and reporting almost from memory), letters and pamphlets.

1780 – cartoon by James Gillray showing greed of Warren Hastings, the governor of Bengal. (Source: British Library)

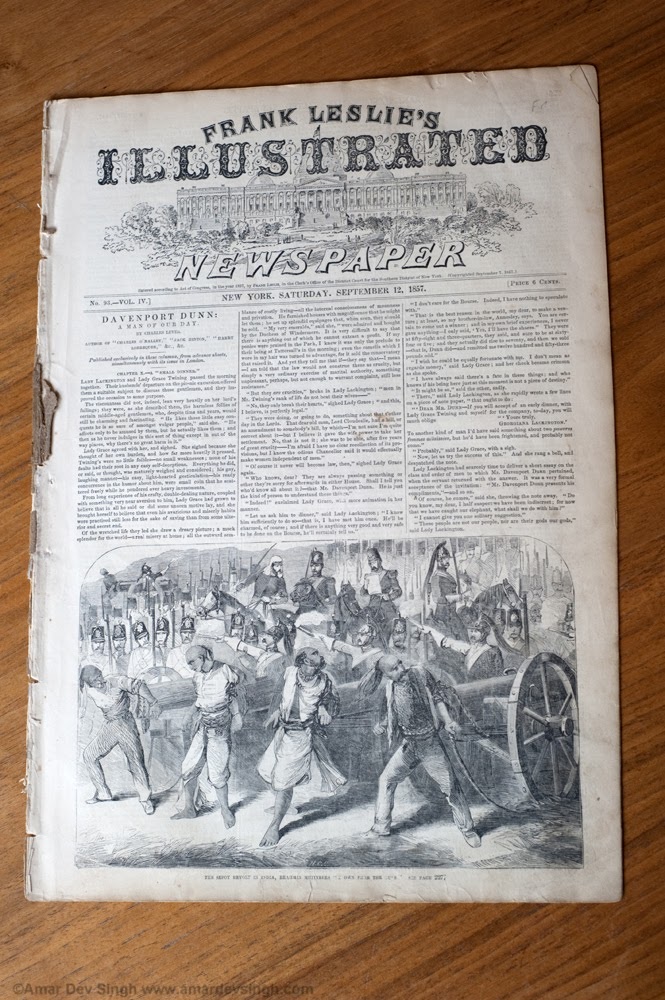

During 1857-58, newspapers in London depended totally on “handwritten despatches” that would take nearly a month to reach them from Delhi.

Reporters reporting Shaheen Bagh were lucky they could send their news immediately. Yet what is most surprising is that the contents, flavour and tone of reporting all three cases was more or less the same.

With the violence taking place in Paris in 1789 and Delhi of 1857, both these events saw a flurry of “opinion journalism.”

Shaheen Bagh, however, did not reflect it in its real perspective as the larger section of media did not opt for it. They simply reported, or ignored it entirely!

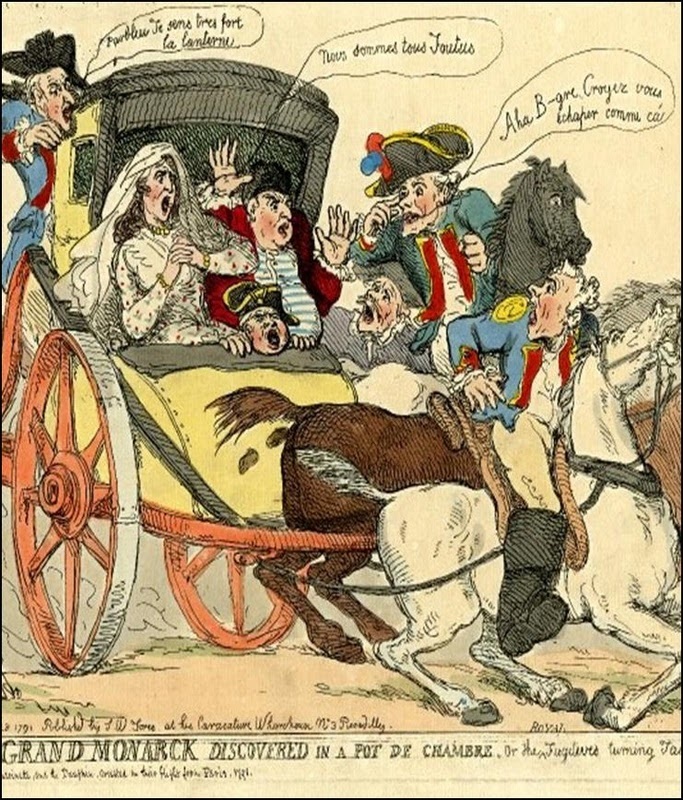

As the era of political cartoons has practically vanished in modern-day Indian journalism, Shaheen Bagh could not manifest itself in this graphic way. But 1789 and 1857-58 were known for portraying mass anger in brain-twisting ways: through cartoons.

Are the good old days of cartoon journalism relating to political upheavals and mass wrath gone? Are the days of cartoons depicting ideas over? Can anybody answer please?

Sepoy Mutiny’s reporting

1789: Reporting a Revolution

The French Revolution always remains journalism-focused as it charted new waters in reporting socio-political upheavals.

Periodicals like L’Ami Du Peuple [Friend of the People], La Feuille Villageoise [The Village Leaf/Sheet] and Le Moniteur Patriote [The Patriot Monitor] played most vital roles in shaping public opinions against kingship, dictatorship and aristocracy.

The year 1789 would be known for innovative headlines such as “Like Paris, Liberty takes France by Storm…General Revolution.” This was the headline when Bastille fell on July 14. It appeared in the Politisches Journal published from Hamburg, Germany.

The German media would often translate the French dailies, letters or pamphlets and print. Germans living in France also wrote letters describing day-to-day developments after the fall of Bastille to their relatives and such letters would be later given to the German newspapers as “source materials” for news.

On July 18, 1789 the London Gazette reported:

“A general Consternation prevailed throughout the Town. All the Shops were shut; all public and private Employments at a Stand, and scarcely a Person to be seen in the Streets.”

The language of Shaheen Bagh reporters is also of similar nature.

A copy of L’Ami du peuple stained with the blood of Jean-Paul Marat

In 1789 the Paris newspaper L’Ami Du Peuple was literally soaked in human blood: the blood of its editor, Jean-Paul Marat.

Marat, a staunch supporter of the Revolution, was murdered while taking a medicinal bath in his printing press. His blood spilled into a copy of L’Ami Du Peuple lying nearby. This copy is still preserved in Paris.

First report of French Revolution

Human blood has no religion, caste, creed or community. It simply has a colour: red. And in all protests, be it against the citizenship law, absolute monarchy like in France or against Kampani Rule in 1857-58, the blood of innocents is always shed.

Readers, you may differ with me, dissent is the very essence of democracy! Please feel free to condemn me if you disagree.

A cartoon of French Revolution

Russell Reporting from Delhi in 1857

Let us turn the pages of the history of news reporting to 1857-58 as it concerned Delhi. Today’s media history knows much about Delhi’s bloody battles of Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-58 through the reporting of William Howard Russell, the war correspondent of the Times of London.

The year 1857 was an “idea” as it made the fact crystal clear that a commercial profit making company like East India Company could not rule a nation: India.

Shaheen Bagh’s reporting was done by the click of computer’s mouse and people knew developments within moments.

When Russell came to Delhi to report in June, 1858, his telegrams would take about a month to reach London.

On arriving in Delhi, he found the town had totally surrendered itself to political chaos, killings, arsons and loot.

Russell’s reports were mostly verbatim of what he saw, emotive, dramatic and used highly visual language. So did many Shaheen Bagh reporters.

The Indian media has many colours and political hues. Naturally, reporters have to toe the line of their newspapers while reporting political chaos. Interestingly, Russell too went on record to ask his editor in a letter: “Am I to tell these things or to hold my tongue?”

Russell’s editor asked him not to hold his tongue, and his reports appearing in the Times created such flutter that the East India Company was ordered by Queen Victoria’s office to stop the executions of Hindustanis in Delhi and Cawnpore.

This is the power of the press, an independent press!

Delhi witnessed bloody scenarios as the East India Company had unleashed a reign of terror in the city’s streets. One of the headlines of Russell’s stories was: “Here… We had a war of religion, a war of race and a war of revenge…”

Do we need to prolong our story? In my opinion, no!

1789: Original Symbol of French Revolution

(Cover Photo: Sepoy Mutiny reporting)