The Big Orange Word Machine

‘People do not see the politics behind it and take it as a sort of entertainment’

Hindutva last week added a new word to its lexicon when its cradle of Gujarat was introduced to the term ‘Literary Naxal’. The state often remembered as the first Hindutva laboratory saw the term introduced in the editorial of a publication supervised by the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi.

It was used to criticise the viral poem Shav Vahini Ganga composed by Amreli poet Parul Khakhar, which has the refrain, ‘Saheb the Ganga carries corpses in your Ramraj.’ Akademi chairperson Vishnu Pandya, appointed in 2017 confirmed to the media that he had penned the editorial attacking it.

In what is perpetrated as a matter of routine to anyone critical of the ruling dispensation, the poet was trolled and hounded online to the extent that she has reportedly gone incommunicado. But her poem was translated into several languages and well circulated by liberal voices.

The episode is only the latest in the long journey of the Hindutva lexicon, which has undergone many changes in the 35 years or so since modern Hindutva took off with the movement to build a Ram temple on top of the Babri mosque.

The term in currency then was ‘pseudo secular’, made popular by leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party like Lal Krishna Advani. The so called Ram Janmabhoomi movement was then targeting Muslims by raking up persecution by Mughal kings, as well as the Supreme Court’s award of alimony to Shah Bano, overturned by the Rajiv Gandhi government to appease the Muslim right wing.

But Muslims or Christians alone would not serve the purpose, as the secular forces had to be targeted alongside them. Having demolished the mosque in a big blow to secular forces, the Hindu right continued to cry ‘pseudo secular’ as its foot soldiers started tasting electoral success over the next decade.

This reporter was witness to some Hindutva leaders trying to establish the difference between ‘Nehruvian secularism’ and the ‘secularism of the west’ as they deposed before the Liberhan Commission probing the demolition of the Babri monument.

By the time the next major event in the communal history of India took place in the form of the Gujarat riots in 2002, the term pseudo secular had been replaced simply by ‘secular’ or ‘secularist’ - to be precise ‘bin sampradayik’ in Gujarati, in a state that is also known for giving the modern world its thinker of non-violence in Mahatma Gandhi.

In the days after the anti-Muslim pogrom that followed the burning of 58 Karsevaks in the Sabarmati Express at Godhra, this reporter frequently heard the Hindutva foot soldiers threatening that the next round of violence would target the secularists.

They also went around claiming with pride that Gujarat had come out of Gandhi’s shadow.

There was a further attempt to popularise the term ‘secular fundamentalist’ but this did not take off, perhaps because opposing fundamentalism was seen as counterproductive, or the footsoldiers did not understand it.

The terms ‘anti national’ and ‘anti Hindu’ too have lived on right from the beginning.

But now, alongside the secular forces it was the NGOs that needed to be targeted. The term frequently used for NGO workers and social activists was ‘jholachaap five star activists’, implying moneyed hypocrisy.

As the internet era drew on, Hindutva trolls coined ‘sickular’ to describe secularism as a disease, and ‘libtard’ for liberals or ‘AAPtard’ for followers of the Aam Aadmi Party, which had started catching people’s fancy, to suggest that they were unintelligent.

As Hindutva gained political power the process of coining new phrases gathered steam, and to the wordsmiths’ list were added intellectuals, students, artists, writers and poets, for that matter anyone who did not agree with them.

Particularly after the agitation upon the Jawaharlal Nehru University, even senior ministers were making reference to the ‘tukde tukde gang’ that would balkanise the country, or the ‘Khan market gang’ rooted to central Delhi, or yet again to ‘Maoists’ and ‘Urban Naxals’ , leaving many to wonder if they knew what Maoism or the Naxalbari movement were all about?

Academics and keen political observers in Gujarat say the entire effort has been a potent weapon to achieve political goals.

For sociologist and political observer Gaurang Jani, “The coining of such terminology is done keeping in mind the typical educated middle class which is both casteist and communal in outlook.

“This process is called labelling and it has intensified over the years since the people, particularly the youth, have to be kept away from alternative thought and views. It works very well with people who subscribe to biased reportage in the media, have no analytical power, no sense of history and are gullible to what is fed.”

Jani told The Citizen that a lot of effort has gone into ushering in their pawns in every institution, including universities where even the topics of seminars are handed out to teachers beforehand.

“But it also shows that the right wing too has to grapple with several issues and it is not just about religion alone. That is why they are coining terms in every sphere. They have to invent new strategies to marginalise people who question their intent.”

According to academic and observer Prakash Shah, “The whole strategy is to give a bad name: call it a bad dog and then kill it. People at large do not see the politics behind it and rather take it as a sort of entertainment.”

Shah too expressed concern at the way the right wing has been eating into various institutions.

With its disastrous handling of the pandemic and crucial state elections in the offing in Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat, surely many new terms will be coined in the months to come.

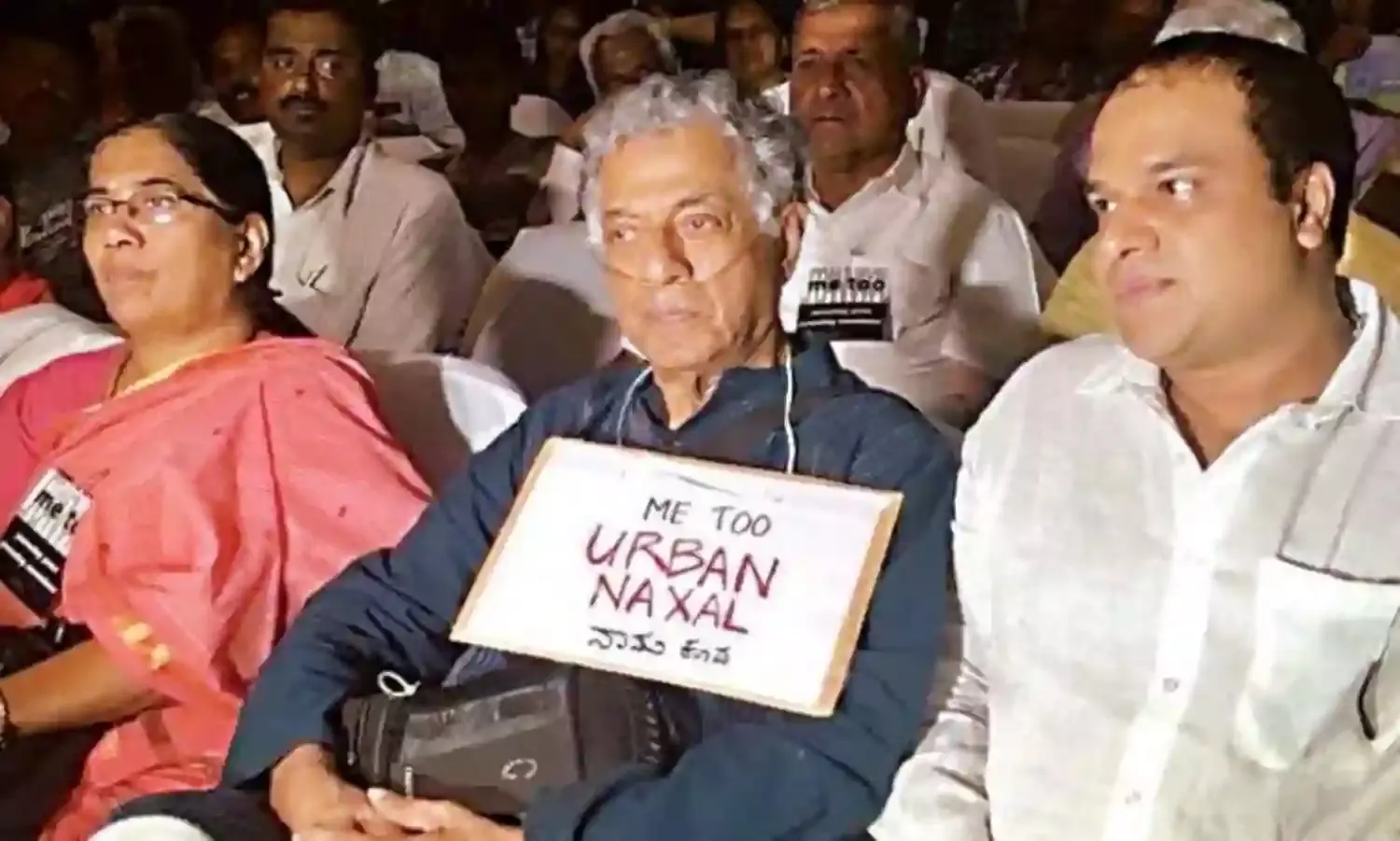

Cover Photograph: Late filmmaker Girish Karnad at a demonstration protesting against the organised attack on ‘‘urban naxals” in Bengaluru. File Photograph