Taare Zameen Par Broke New Ground For Children In Indian Cinema

Taare Zameen Par: Finally a real depiction of children in cinema

Unlike the cinema of Turkey and Iran, Indian cinema pays scant respect to children as an audience, as central to the narrative or even as a significant character within the film. The dilemma of how to represent issues that directly influence or affect children in different ways does not appear on the as a strong agenda for Indian filmmakers. The Children’s Film Society founded by the government of India hardly bothers about promoting and marketing its films. Can one really believe that the Children’s Film Society has a meagre collection of around 450 films in its more than five-decade-old history?

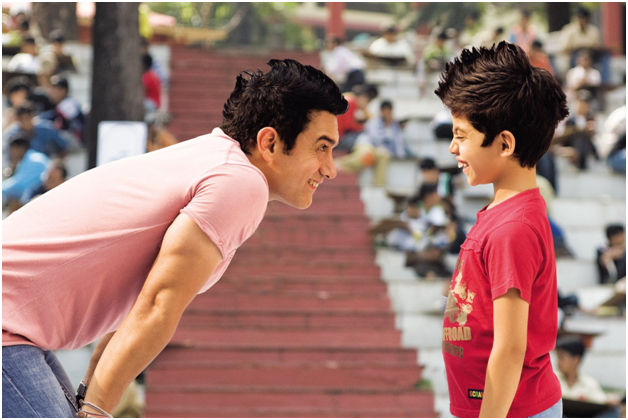

Till Yash Chopra’s box office hit Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, the child character was everything but a child. It talked and behaved like an adult and often became agency for the romantic pair in love. The child in film irritated more than entertained. The characterisation was loud, crude and they mouthed precocious lines that were more ‘adult’ than adult. So, when did the situation change to present the child as a child and not as an adult-in-miniature? One might perhaps point out Taare Zameen Par, an eye-opener packaged in entertainment format. It marked a turning point in the evolution of the character of the child in Hindi cinema.

Setting a rare example, Taare Zameen Par turned out to be a strong socio-political statement on ignorance among parents, teachers and educators about little-known disabilities their children suffer from such as dyslexia. Yet, the film was a blatant commercial film designed to tug at the heartstrings of the audience and rake in the big bucks. There is no backing out from the fact that the film introduced the Indian masses to a new term a learning disability called – dyslexia. The nation woke up.

In a nation with a population of around 1.2 billion people that produces around 1000 films per annum, there are very few films targeted at a child audience. According to the 2011 Census figures, children between the ages of 0 – 14 form 29.5 of the total population. Yet, there are hardly films being made for our children. According to Jenkins in his essay in Handbook of Children, Culture, and Violence (edited by Nancy E. Dowd, Dorothy G. Singer, Robin Fretwell Wilson, SAGE Publications, 2005),the conception of childhood innocence is constructed through child performance in film and this construction presumes that “children exist in space beyond, above, outside the political.” (p.331). But is this feasible or necessary in relation to the presentation and portrayal of children in Indian cinema?

Yet, one cannot afford to skirt the lack of celluloid reflections of reality of Indian children and childhood. There have been few explorations into childhood violence where children find themselves helplessly trapped both as consumers as well as perpetrators of violence besides being victims of violence.

Boot Polish and Taare Zameen Par stand out as classic examples of children as victims of violence. Boot Polish (1954), treated the plight of children as social problems. The two orphaned kids are forced to confront the harsh realities of poverty within the slum environment in a merciless city like Bombay. The film closes on a note of empathy and a positive resolution for the two orphans. Violence is inflicted on them because they are very poor and unlettered orphans with no one to take care of them. In Taare Zameen Par, Ishaan Awasthi lives within a close-knit nuclear family with an older brother who is brilliant. His parents are educated and affluent and want the best for their sons but they are not aware of what exactly is wrong with Ishaan nor do they try to find out. They seek to escape by putting him in a boarding school where his situation becomes more precarious.

Sheila Ki Jawani directed by Zoya Akhtar in Bombay Talkies comes across as a sharp indictment on parents who seek vicarious satisfaction through their children by forcing them to pick things that are against the children’s nature and desires. The little boy loves to dance. His dream is to perform Sheila Ki Jawani while his dominating father wants him to excel in team sports.

What we need are films that show the director and the script treating children naturally, teaching them to act with spontaneity and presenting them as children. Films centered on children targeted at a universal audience where parents could also take a tip or two has now come into being.

Contrary to Macaulay Culkin, the highest earning child star in the history of Hollywood after Home Alone (1990), child actors in India have limited power over the formation and circulation of their identity in a wider context. This has worked out more as a liability for Indian child actors. In the past r, when child stars were in great demand, parents of child actors like Baby Naaz, Daisy Irani, Master Romi and Honey Irani were constantly dictated to by their parents who shaped and exploited the star personas of their children while the going was good. Often, these child stars either lost out when they became adults, no longer in demand, or were relegated to marginal roles in feature films. In a documentary on child actors by Dilip Ghosh entitled Children Of The Silver Screen . one hears at first hand, how Naaz was exploited by her own parents and how Daisy Irani hardly ever went to school and was pinched on the sets for a crying scene if she failed to bring out the tears and fed with chocolates to give a good shot.

In 2010, Sudipto Chattopadhyay, inspired by Ghosh’s film, made Pankh. The film is reportedly based on the true story of child actor Ahsaas Channa who was really a girl forced by her mother to portray a boy in films like Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna and Vaastu Shastra. When this child, in the film grows up and tries to make it as an adult actor in films as a female star, she fails to make it and becomes a drug abuser who has never been to school and is compelled to remain trapped within the four walls of her home. In real life, she has become an actress in television serials. Says director Chattopadhyay who has also written the story and the script of Pankh, “With parents taking up the dictators' role, the kids tend to shrink. And as a result of cross dressing, their public persona becomes an agenda. Their real self is hidden.”

The scenario is not as grim as it appears. Many good children’s films in recent times have either walked away with National Awards in different departments of filmmaking or have made it to international film festivals. I am Kalam, Chillar Party, Gattu and Stanley Ka Dabba are examples. Others are Anurag Kashyap’s Hanuman, Vishal Bharadwaj’s Makdee and The Blue Umbrella, based on a story by Ruskin Bond, and Priyadarshan’s Bumm Bumm Bole, the authorized adaptation of the Iranian film Children of Heaven. India is not a nation where the image and performance of children can be used to depoliticize their narratives. Yet, through films like Taare Zamin Par or the old Boot Polish, the films and the children within them, as actors or as real children resurrect and recreate issues and problems while reminding us of truths we try to brush away from our cultural memory.