Homage To Hollywood Heists- With A West Bank Twist

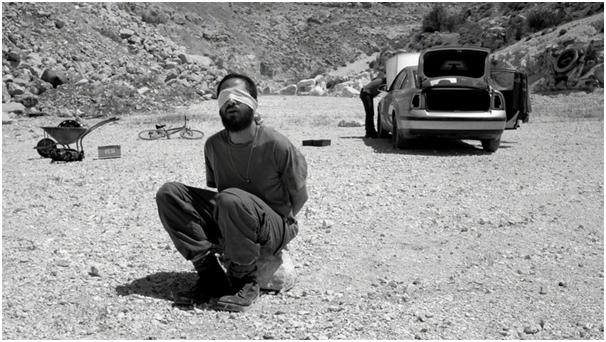

A scene from Love, Theft and Other Entanglements.

Love, Theft and Other Entanglements directed by Muayad Alayan, Palcine Productions

It sounds like the plot of a heist film from the golden age of Hollywood: a small-time thief steals a car, little knowing what’s in the trunk.

But instead of winding up pursued by the mob or a dogged private eye, Mousa — the protagonist in Love, Theft and Other Entanglements — finds himself with both the Israeli security services and a Palestinian militia group on his tail.

Mousa, played by Sami Metwasi, is a thief whose latest job is a vehicle which contains a gagged and bound Israeli soldier, something he finds out only after he has started selling off parts of the car. The resistance fighters need the soldier back so that they can force the Israelis into an exchange of prisoners. The Israelis, of course, will happily use violence and blackmail to stop the swap.

What follows is a deftly constructed, brilliantly acted chase through the chaos into which Mousa’s life descends. Brought up in a refugee camp, working for a bullying boss on an Israeli construction site and living with a (justifiably) angry father who wants him to pull his life together, Mousa just wants to get out of the occupiedWest Bank.

The stolen car was supposed to be his golden ticket, furnishing him with the cash to pay for forged papers to Europe.

To make things even more complex, there is also Manal, the love of Mousa’s life, played with tired, bruised emotion by Maya Abu al-Hayyat — also seen in Omar Robert Hamilton’s short movie Though I Know the River is Dry, but perhaps better known as an accomplished poet and novelist.

Manal lives a luxurious life with her rich husband, and not only is she an emotional entanglement to complicate Mousa’s plans, but as events become more tense and dangerous, she is another source of vulnerability for him.

To outline much more of the plot would give away too much for those who are lucky enough to see this film — and anyone with the opportunity should try.

Filmed on location in Bethlehem and Jerusalem, and with a small but dedicated cast and crew who worked on a shoestring budget, Love, Theft and Other Entanglements is nevertheless a tightly directed, intelligent, stylish piece of filmmaking.

The unusual decision to film in black and white was, according to director Muayad Alayan, who spoke at the film’s UK premiere during the Edinburgh International Film Festival, intended to create a sense of distance and unreality.

“Audiences are used to a certain feel,” Alayan suggested, as a result of the many documentaries and films about the occupation which have come out of Palestine in recent years. Instead, he wanted to highlight the absurdity of the situation, permitting his story some independence from its setting.

In addition, the monochrome aesthetic increases the film’s feel of an homage to classic Hollywood heist movies, with their snappy style and sense of teetering on the line between farce and stark violence.

In this film, we get a little of both, but not too much of either.

On the side of farce, Sami Metwasi reveals a comic ability with touches of Danny DeVito or Charlie Chaplin. As Mousa’s plans are more and more comprehensively wrecked by events, Metwasi becomes a jumpy, staccato ball of tension, leaping and yelling in frustration and impotent fury.

A trained dancer and musician as well as an actor, Metwasi brings a restrained physicality to the role which lightens what could become a forbiddingly dark plot.

Credit for helping to create the half-panicked, half-farcical atmosphere of chases and kidnappings also goes to the film’s score, particularly the atmospheric jazz tracks by Black Flower.

One of the most impressive aspects of the film, especially given that it is Muayad Alayan’s first feature-length movie, is that this comic side never outstays its welcome.

As Alayan and Metwasi reinforced at Edinburgh, Love, Theft and Other Entaglements is intended to be a film in which the occupation is the backdrop, not the story.

But it is the underlying cause of many of Mousa’s dilemmas — his poverty, his desire to escape and his predicament trapped between Israeli secret police and Palestinian militiamen.

But what comes out most strongly is that Mousa is one of the little guys, and he has no control over the greater forces which buffet him one way and another. He isn’t a hero, a villain or indeed entirely a victim.

In a moment of brutal self-knowledge, Mousa recognizes a nobody like himself in Avi, the kidnapped Israeli soldier. Avi is a jobnik — the soldier’s own description — rejected by Israeli army radio for his lack of talent and for “just doing his service” as a low-level conscript.

When Avi starts to sing tunelessly, Mousa comments that “this is why they didn’t send any tanks or planes to rescue you.” The cutting line could be delivered to himself, and he knows it.

But, as it turns out, he has reserves of strength and dignity within him which no one — least of all Mousa himself — might have expected. When he is finally forced to make choices, in the face of pain, violence and loss, he manages (at least sometimes) to speak truth to power and to put the needs of those he loves above his own.

As the director and lead actor have emphasized, this is not an “issue” film, even if both have also acknowledged that the occupation colors every element of the film’s environment. It is a subtle, pacey, entertaining and moving piece of cinema, far more confident than one might expect of such a young director and far more slick than one might expect of a film made with such a low budget.

I’d urge anyone who wants to experience what creative, mature Palestinian cinema can look like to see it.

(Sarah Irving is the author of a biography of Leila Khaled and of the Bradt Guide to Palestine and co-editor ofA Bird is not a Stone, a collection of contemporary Palestinian poetry in translation. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh.)

(ELECTRONIC INTIFADA)