‘Jai Bangla’ Drowns ‘Jai Shri Ram’ in West Bengal

Polls 2024

Chants of ‘Jai Bangla’ have thwarted the Hindutva war cry of ‘Jai Shri Ram’ in West Bengal, even as figures from one round after another of vote counting kept adding to the Trinamool Congress (TMC) Lok Sabha tally.

By 8 PM on Tuesday, after 12 hours of counting, Mamata Banerjee’s party (TMC) had won, or was leading in 29 of the state’s 42 seats. It won all 29. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), its main challenger, won 12.

The BJP has now lost a third of its 2019 Lok Sabha tally, its best showing ever in the eastern state. The saffron party has been eyeing West Bengal for a decade now. The Indian National Congress managed to hold on to only one of its two seats. The Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPM) failed to score yet again.

All the seats that the others lost went to the Trinamool. The party received nearly 46% of the votes polled while the BJP garnered about 38%, which is more impressive than its national tally and close to its vote share in the 2021 Assembly elections, but below the 40.7% it received in 2019. The TMC had bagged 43.3% and 48% respectively in 2019 and 2022.

The CPM’s vote share inched up marginally from 2021 levels to 5.6%, still a percentage point below what it got in 2019. Similarly, Congress’s 4.7% was better than the abysmal 2.9% of 2021 but nearly a percentage point below 2019.

The state Congress, under Adhir Chowdhury, had teamed up with the CPM-led Left Front as part of the I.N.D.I.A bloc. Both he and Md Salim, the CPM state secretary, lost (from Baharampur and Murshidabad respectively).

However, Congress’s Isha Khan Choudhury has managed to protect his family bastion Malda Dakshin. The CPM’s much talked-about youth brigade also mostly bit the dust.

Trinamool supporters had started the revelry early, throwing the party’s customary green abeer (coloured powder) and bringing out the ceremonial conch shells and kansar ghanta (bronze percussion bells), in the sweltering Tuesday afternoon itself. As the tally moved closer to what TMC General Secretary Abhishek Banerjee predicted, their decibel level climbed up joyously.

Their reaction was coming after a long, seven-phase polling process, all through which the BJP central leadership had peppered the state with visits by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah. The big guns had not stopped shy of claiming around 30 seats from the state.

A party sympathiser from north Bengal had told this correspondent that “BJP was sure of winning 28-30 seats, after which they will move against the CM and her nephew Abhishek to ensure they are put behind bars”.

Abhishek, considered the second-in-command in the party, had claimed that the party would win 23 of the 33 seats that had polled in the first six phases. He missed the mark by a mere three seats. The nine seats in the last phase, in the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Area and the Sundarbans, are considered to be a TMC bastion and remained so.

Abhishek won from Diamond Harbour seat for the third time, this time by over 7.1 lakh votes. It would have been a national record, but for the even larger 10 lakh-plus margin that Congress’ Rakibul Hussain scored from Dhubri in neighbouring Assam.

In the evening, CM Banerjee lamented that her party lost a few seats due to votes split by the CPM-Congress candidates. She was quick to add that the Congress central leadership was not to be blamed for this. Trinamool candidate Krishna Kalyani lost to BJP’s Kartick Paul from Raiganj by 68,197 votes even as Congress’ Ali Imran Ramz aka Victor secured over 2.6 lakh votes.

In Purulia, TMC’s Shantiram Mahato trailed BJP’s Jyotirmay Mahato by a little over 17,000 votes while Congress veteran Nepal Mahato secured about 1.3 lakh votes and Independent candidate Ajit Mahato was inching to a lakh votes.

In Bishnupur, Sujata Mondal was trailing her estranged husband and BJP candidate Saumitra Khan by 6,670 votes while CPM’s Sital Kaibartya had bagged over a lakh votes. Banerjee, however, overlooked the fact that such third-place candidates were not necessarily eating into her votes but could as well be anti-incumbency votes against her government.

In fact, through much of the campaigning process, it seemed that it was the state government that was to do all the answering and not those in power in the Centre for a decade. Not only Modi’s BJP, but also the CPM and the state Congress contributed to this narrative in varying degrees.

There were instances when the tallest of Trinamool leaders would proclaim from their campaign stages that the onus of providing answers was on Modi, and not on them.

But the curveballs from the Opposition kept coming. Be it cases registered by central agencies like the Enforcement Directorate (ED), Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI); allegations of corruptions and scams; the Sandeshkhali episode that started with charges of land-grabbing but escalated to sexual abuse before being debunked by a series of sting videos; a communal rhetoric, the attack was relentless and concerted.

What then did work for Team Mamata? While analysts will keep working the numbers, here are a few quick out-takes:

Welfare schemes: Corruption charges were levelled thick and fast against the Trinamool party and the state government. But the universal nature of Mamata’s schemes (rather than being targeted at some people) struck a chord.

Nobody could say that they were deliberately being kept away from accessing Lakshmir Bhandar, a monthly payday for women cutting across social groups. The same can be said for the health insurance scheme Swasthya Saathi.

While Kolkata-based activists were busy tying themselves in knots to claim that such a scheme was not desirable over a more robust public healthcare system, citizens were eager to get hold of their cards (in line with similar schemes by the Centre and some other states).

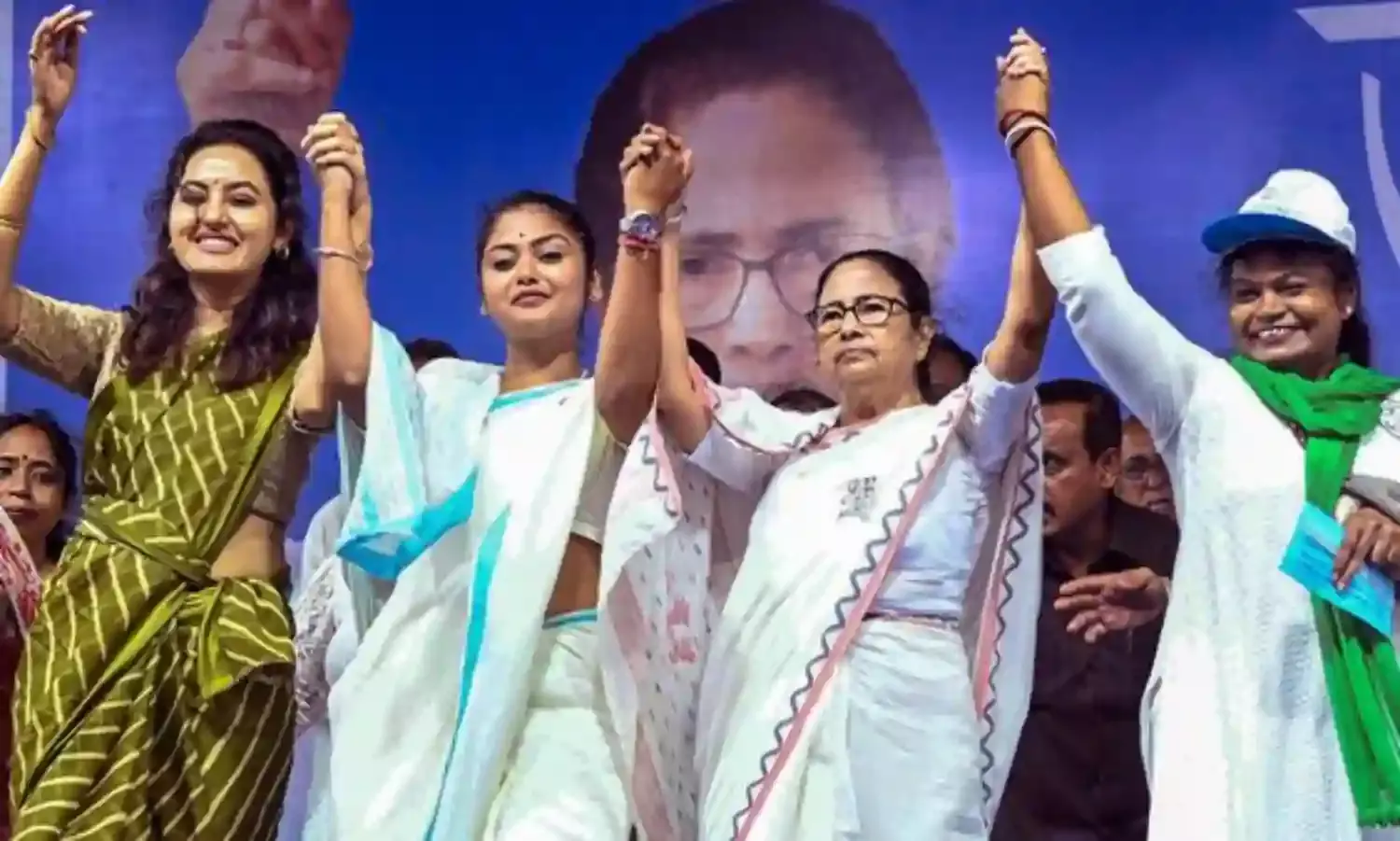

Women of Bengal: Banerjee has always shied away from being identified as a woman leader or a Chief Minister, at times to the annoyance of gender activists. But she has been steadfast in putting the focus on women: Trinamool’s slogan of Maa, Maati, Manush (the Mother, the Land, the People) also is a popular reminder of that.

Unlike many other parties, the TMC visibly plays up the involvement of women in its rank and file, especially those from lower middle-class families. Even among Tuesday’s pack of 29 probable members of Parliament, 11 are women. That’s more than a third — a rate any party would find hard to match.

Women’s participation in Indian elections have steadily increased to the point where women voters outnumbering men is no more uncommon. Many astute politicians, including Bihar CM Nitish Kumar and Odisha CM Naveen Patnaik, have carefully nurtured women as a constituency and reaped rich electoral dividends.

While it is debatable whether adequate political representation has yet become a hot topic, Banerjee has put women in the centre of many of her government’s plans of action — in line with recommendations by global development agencies.

Be it Lakshmir Bhandar or Kanyashree, a United Nations-recognised conditional cash transfer scheme to prevent dropouts and early marriages, which is widely prevalent in Bengal, such schemes widely thought to have ensured her popularity among 50% of the voters continue unabated.

Social cohesion: Banerjee has been careful of protecting her secular credentials even after exiting Congress and forming Trinamool a quarter century ago. Even when she participated in BJP stalwart Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s Union government, she took care to distance herself from the post-Godhra carnage.

Following a rout in the 2006 Assembly elections, she started paying even more attention to the minorities, especially the Muslim community who form more than a quarter of West Bengal’s population: Even the BJP has tried to woo the community here, on and off.

Relentless charges of ‘appeasement’ and ‘vote bank politics’ from the BJP have failed to budge Trinamool from this stand. Even amid the poll process, the party showed spunk in the face of a Calcutta High Court decision to cancel a series of ‘Other Backward Classes’ reservations in its tenure extended to a gamut of Muslim populations.

“It is true that the state government doesn’t take out many vacancies now, but it is also true that whatever little it did take out, has ensured better representation,” said a Muslim activist who works with a leading non-profit. Consequently, the CPM and Congress have been playing catch-up.

At the same time, the Trinamool hasn’t shied away from making its presence felt among the ever-increasing Hindi-speaking migrants from Bihar, Jharkhand and eastern Uttar Pradesh.

In the last five years, it has also sharpened its outreach among Scheduled Tribe communities, especially in the south-western ‘Jangal Mahal’ region. Tuesday’s results are proof; it has succeeded in snatching away the Tribal-dominated Jhargram seat from the BJP.

Religion vs Culture: The BJP has brandished an aggressive brand of Hindutva politics, resplendent with armed Ram Navami processions and ‘Angry Hanuman’ iconography, in the last decade or so to register handsome gains in members, supporters and voters.

Despite all such efforts, however, it has failed to increase its vote share to the point of being Party No.1. In that respect, West Bengal has held out and not followed all other north Indian states.

Its effort to paint Mamata as a Muslim sympathiser and anti-Hindu also did not work beyond a point, what with Banerjee being a Brahmin surname and the CM being unabashed about demonstrating her Chandipaath (recital of hymns to Kali) skills or her government patronage to local clubs during Durga Puja.

The more BJP has tried to throw Hindutva at the TMC, the more the latter has brought to the fore several local deities and their festivals. Banerjee and her party members have relished any opportunity to celebrate, repeatedly underscoring faith is personal and festivals are for the people.

Last seen, the right-wing system has been busy trying to bring as many local Hindu religious orders as they can under their umbrella. But the jury on that is still out.

Bengal vs Outsider: ‘Jonogoner Gorjon, Bangla Birodhider Bisorjon’ (Roars of the people, Sink those against Bengal) was paraded out as a war cry by Trinamool General Secretary Abhishek Banerjee at the beginning of the campaigns.

Ever since, in every single rally and public meeting, he and his aunt and every party leader worth their salt have not missed a chance in painting Modi and the BJP as anti-Bengal. They have been likened to ‘Delhi-based zamindars’, a word that is politically loaded even now, generations after land reforms. The forced ouster of Mahua Maitra from Parliament provided the TMC with another weapon in their arsenal.

As they have been likened with invaders from Delhi who withhold Bengal’s dues (read MGNREGA payments), the BJP’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh-tinted state leadership has repeatedly failed to read between the lines that they are being likened to the Delhi Sultanate of yore extorting taxes from the Bengal rulers. The irony: Modi and Shah have been overeager to paint the Mughals and other Sultans as tyrants.

Attacks Boomerang On BJP: More often than not, the BJP tried to blow up an issue but blew up on its own face. The Modi government lined up a posse of central agencies to dig out dirt on TMC and send its leaders behind bars; it ended up being charged with high-handedness, political manipulation and vindictiveness.

The Centre stopped funds alleging irregularities in schemes like MGNREGA; Banerjee happily proclaimed from every available stage that the Centre was refusing to let go of Bengal’s rightful dues.

The saffron party raised a stink on teachers’ recruitments and celebrated a HC order scrapping the process; the state moved the Supreme Court, continued to pay salaries to the teachers and sent out the message that the BJP was stealing jobs from the people. The playbook had changed.

BJP vs BJP: Gossipmongers in Delhi have often chucked at Amit Shah’s drive to woo Congressmen away claiming it has ‘Congressised’ the BJP; Now the Bengal BJP has to seriously think whether the induction of Suvendu Adhikari from Trinamool has Trinamoolised state BJP.

As if the exit of high-value leaders like former Union Minister Babul Supriyo, was not enough, this time a large section of the state BJP was dismayed at former party state boss Dilip Ghosh being made to change his seat from Midnapore (his backyard) to Bardhaman-Durgapur.

Ghosh, who had single-handedly built the second-generation of the party in Bengal after the earlier leadership had either retired or stopped trying, fought the battle nonchalantly. And the RSS pracharak remained nonchalant even after a near-1.4-lakh defeat. But that won’t be enough to stop tongues from wagging in state BJP.

‘Senapati’ Abhishek: He had it all ready in front of him as the nephew of the party chief. He landed in Parliament at 26. From the word go, there have been accusations of high-handedness and corruption in the grapevine.

But slowly and steadily, Abhishek Banerjee has cemented his place in a party that would earlier swear by only one name: Mamata Banerjee.

True that he never had to face sibling rivalry like Tejasvi or Stalin have had to, but Abhishek’s actions have often drawn the ire of party veterans and given rise to a senior vs junior rift; or, for that matter, consternations over his fondness for election maverick Prashant Kishor.

At one point, before the elections, it seemed that he would sit this one out and not focus much outside his own constituency. But Mamata made sure he was in the thick of things, commandeering battalions of eager party workers, formulating attack strategies, deploying resources and even sitting in for her at INDIA coalition meets.

On his part, he made a public display of an undying allegiance to the CM. His tactical manoeuvres were exemplified when soon before the third and fourth phase a series of sting operations sought to disprove charges of sexual violence in Sandeshkali.

Abhishek went from meeting to meeting, playing them on stage before large gatherings. “Abhishek’s calculations were surely a large factor in the victory”, said Satabdi Roy on Tuesday, en route to her fourth victory from Birbhum.

Brand Mamata: Former United States President Ronald Raegan used to be called the ‘Teflon President’ as no lapses seemed to make a dent on his image, Many years later, a columnist repeated the moniker for Bengal’s longest-serving CM Jyoti Basu. That doesn’t even sum it up for Mamata Banerjee.

The more she comes under attack, the more seems to be her penetration in the current Bengali society. The more her detractors make a beeline for the BJP, the bigger it seems to be TMC’s electoral gain.

The more she seems to age, the more unwavering seems her drive to hit the campaign trail. This time, she started out by camping for a couple of weeks in north Bengal. Earlier too, she has spent time at the secretariat there without hardly drawing political gains but never complaining much or giving up.

This time, while in the middle of a cyclone relief work there, she spread herself as thin as she could. On the face of it, it didn’t yield much, but Nishith Pramanik, one of the deputies in Shah’s home ministry, lost the race unceremoniously. In Alipurduar and Darjeeling, BJP’s victory margin is a third of what it was in 2019 and in Jalpaiguri it has been halved.

That was just the beginning. In the end, Banerjee, who will turn 70 in six months, crisscrossed the length and breadth of the state, throwing a direct challenge to Modi’s repeated visits, took to the stage even in unscheduled stopovers.

She finally brought out her trump card of hitting the streets rather than taking the chopper in this day and age of fitbits and social media connect. The result speaks for itself.