To Dharavi, With Love

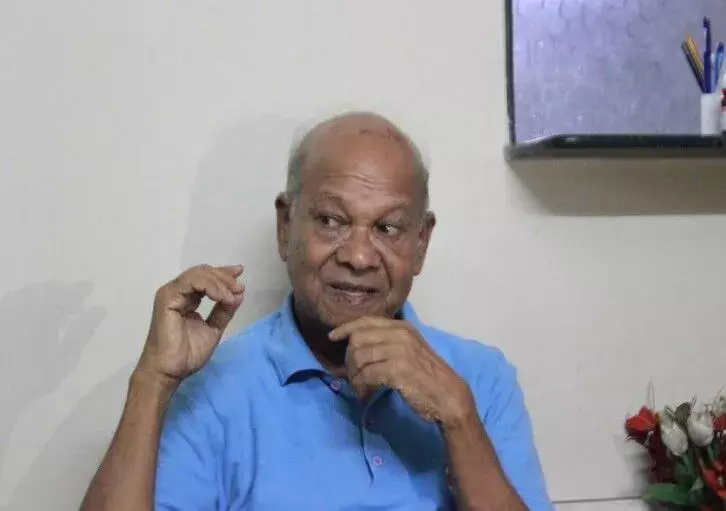

Celebrating the extraordinary life of Bhau Korde

Bhau Korde is almost 85 years old. I first met him in 2019, on an extremely rainy evening in the heart of Mumbai’s Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum. My first meeting with this energetic, talkative and warm father-figure left an indelible impression. Bhau Korde, Dharavi’s own powerhouse of social service, has had an enviable over 50 years’ track record of social activism.

Most people might think of Dharavi as a huge slum, best to be avoided. However, once you spend some time here, you will realise that, if Mumbai is the financial capital of India, Dharavi is the engine that runs Mumbai.

According to Bhau Korde, “Dharavi was a large expanse of open, barren land. The original inhabitants of Dharavi were the Koli fishing community. Around 1867, the first migrants arrived: Tamil Muslim traders. They were given land for a mosque by the Kolis.

The Muslim traders later brought with them Dalits leather workers from Tamil Nadu. These Dalits, who were traditionally banned entry into Hindu temples, got land for their Ganesh temple from Shelu Seth, and erected their own temple in Dharavi, almost two centuries ago.

Gradually, Dharavi began to attract workers and entrepreneurs from all over India. It became the abode and refuge for thousands of homeless and landless migrant employees and labourers, who came to Mumbai in search of livelihood.

It is a mini-India; almost every religion, race, caste, language and culture of India is to be found in Dharavi. The people of Dharavi are hard-working, peace-loving, compassionate, progressive and united, despite all the challenges they face as the have-nots of Mumbai, despite being labelled as illegal and illiterate intruders.”

Bhau Korde’s father, a small businessman, migrated to Mumbai in 1924, from one of central Maharashtra’s remote rural regions. He lived on the outskirts of Dharavi. Growing up in a family of six siblings, Korde had a very humble upbringing and could not afford to study beyond the 10th standard.

Young Korde secured a job as a non-teaching staff member in Dharavi’s only government school then, an aided school at Sion. This paved the way for him to not only educate himself further, but also to open the doors of education to others.

He made it a point to ensure that the Dalit or untouchable children, who were not allowed entry into educational institutions, were admitted into the school he worked for. He went out of his way to develop cordial relations with the parents of these children and to bring them into the social mainstream.

He did the same for children from nomadic tribes and other marginalised communities, who were not given access to education, by making their parents aware of the need to enroll their kids in the school.

This involvement with the ‘untouchables’ and tribals resulted in Bhau Korde’s interactions with the nomadic tribes of Maharashtra, especially the Pardhis, who were unjustly categorised as a ‘criminal’ tribe by the British, due to their anti-British stance. The people of this tribe were not allowed to stay permanently in any village and were denied access to education and employment.

Bhau Korde, together with Indian and foreign social workers, dedicated 10 years of his life to uplifting such marginalised nomadic tribes. He was involved in fighting in court for their rights, ensuring punishment for those who discriminated against or exploited them, and opening the doors of education and employment for them.

He and his associates succeeded in getting court orders de-criminalising the Pardhi tribe and restoring their social status and dignity.

The next phase of Bhau Korde’s life was spent in doing social work projects with the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai. He also worked with the TISS Unit for Media and Communications, now the School of Media and Cultural Studies, on making socially relevant documentary films. He then got involved in intensive relief and rehabilitation work in Maharashtra’s Latur district, following the deadly earthquake of September 1993.

However, the turning point in Bhau Korde’s social service mission came with the devastating Hindu-Muslim riots in Mumbai, following the Babri Mosque demolition, in 1992-1993. As Bhau puts it, “I had thought that having lived in Dharavi since my birth, I knew all about Dharavi and its people.

“But I was shocked and shattered, when Hindu and Muslim communities, who had lived together peacefully for close to a century, started attacking, looting, burning and killing each other! I could not enter certain areas of Dharavi due to the burning and violence.

“I contacted other social activists in the area and decided that we had to do something about this. We could not allow our beloved Dharavi to burn like this. We decided we had to immediately open the doors to dialogue and reconciliation.

“We started visiting Hindu and Muslim families, talking to them, asking them why and how the violence had started, how long they had been in Dharavi, and what had changed their attitudes towards each other.”

Bhau Korde’s initiative to reach out to and make friends with the minority Muslim community resulted in perhaps the greatest friendship and partnership of his life. He met late Waqar Khan, a small garment trader turned social activist having his roots in Uttar Pradesh.

Waqar Khan, a man of great eloquence, charisma and wisdom was a true prophet of inter-religious unity and understanding. Bhau Korde played a major role in Waqar Khan’s videos, posters, songs and speeches calling for an end to violence and uniting people of all faiths. Waqar Khan’s ‘Hum Sab Ek Hain’ (We are all one) poster saved Dharavi from burning further.

It was a picture of four children dressed in Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Sikh religious dresses. No child was ready to shave his head to look like a Hindu Brahmin priest. Waqar Khan then made his son Gulzar play the part. Korde and Khan together worked in the “Hum Sab Ek Hain Foundation”, engaging in every possible activity to restore the broken social fabric.

A pamphlet with ‘The Hum Sab Ek Hain Poster’, was prepared by the women of Dharavi, to foster communal harmony through Iftar gatherings.

One of the first things that Korde and Khan did was to take an initiative to break down a wall that had come up overnight in Dharavi, separating the Hindu and Muslim areas. Korde succeeded in convincing the people themselves to break down this dangerous wall and to defeat the dangerous political games being played in Dharavi by outsiders.

Bhau Korde and Waqar Khan involved Muslims in the organisation of the Ganesh festival. It became a secular festival, with Hindus, Muslims and Christians participating in the various competitions and Muslims arranging for the prize distribution.

At the same time, during Ramadan, Korde involved Hindus and Christians in arranging Iftar dinners for the fasting Muslim community. Korde made it a point to distribute the Quran in various languages and encourage non-Muslims to read and discuss the Quran. “I was surprised to know that, in Dharavi, there were Hindu families, who fasted during the entire Ramadan month, along with their Muslim neighbours!” recalls Korde.

Bhau Korde and Waqar Khan accomplished many remarkable things in their beloved Dharavi. Korde recalls how both of them would step in to ensure that there was peace and progress, and never an incident of violence.

This involved stopping rumours, immediate intervention and holding talks with all stakeholders and the police whenever there were tensions between Hindus and Muslims. Korde and Khan even achieved miracles like the happy marriage of a Hindu boy and a Muslim girl, overcoming stiff opposition from both communities, by holding peaceful talks with local RSS and Muslim leaders, while protecting the young lovers.

“I am very proud of the people of Dharavi, who accepted and understood our message of unity, and who are living proof of the great unity in diversity of our country. I am proud of my cosmopolitan Dharavi… good work is always done by the ordinary people, the masses, who are never recognised.

“We have a lot of things to teach the country and the world, though we are poor and less educated. We do not give a lot of speeches, but we believe in walking the talk. We don’t do things to make a show but live for each other.

“I cannot forget how the third and fourth generations of our young boys and girls are carrying our legacy forward. And of course, the women of Dharavi, Hindu, Muslim and Christian women, have worked selflessly for peace and progress.

“I remember how they used to organise women’s Iftars during Ramzan, in the local churches, for women of all communities. Women refused to be ghettoised and separated; they were ashamed of the riots and led the resistance against rioters.

“They never preached but came up with so many ingenious ways to maintain communal harmony, so many common multi-cultural activities and trained the younger generation as well. I recall how we all worked together in the local Mohalla peace communities, with great police officers like Julio Ribeiro and Satish Sahney, women leaders like Sushobha Barwe, Amina, Bilquis, Sister Reena, actors like Farooq Shaikh, with writers and professors, fantastic social workers like Baba Amte, Medha Patkar and others from all over India.

“Dharavi has a centuries old tradition of inter-faith harmony; I know of Muslims and Hindus paying respects at and celebrating each other’s religious festivals; Dharavi is a very safe area for women; it has the largest number of businesses in Mumbai. There is so much to be proud of about Dharavi.

“I have met the Nobel prize winning author Orhan Pamuk here. I was invited to share my experiences at the University of Columbia and later to Brazil, though I am not fluent in English. People everywhere are inspired by the story of Dharavi. All this happiness I got because of my Dharavi,” said Korde.

He has his grievances against people, who use Dharavi as a temporary showpiece, and later forget about continually supporting the people of Dharavi or highlighting their positive contributions to society.

He remembers being shocked at certain events showing blatant discrimination: “My friend and coworker Waqar Khan could not go to the UK despite an invitation from the London School of Economics because he was refused a visa, and hence the London School of Economics cancelled the event where both of us were to speak.” These are the things that disappoint Bhau Korde.

However, Bhau Korde’s mission is much larger than his personal grievances. During the two waves of the Covid-19 pandemic, Korde continued to contribute to relief missions in and around Dharavi. With Bhau’s active support and guidance, Gulzar Waqar Khan (son of the late Waqar Khan) led a host of NGOs and youth activists in distributing essential supplies to jobless families on the brink of starvation and in successfully conducting vaccination and sanitation drives.

Korde and his associates also helped educate children, especially young girls, who had missed school/college or had no money for tuition, during the pandemic. Dharavi emerged as a shining example for the country, with its exceptional handling of the Covid-19 crisis.

As Korde puts it, “Our stories need to be heard globally because all the big work is done by the small people who are never recognised... We hate it when the big people encash our poverty, make a business out of communal harmony, and turn refugee camps into an NGO tourism initiative.”

Dr. Rosita Joseph Valiyamattam is a visiting professor in English literature. Views expressed are the writer’s own.