A Centenary Tribute To Tapan Sinha

His telefilm ‘Didi’, is a must watch in current times

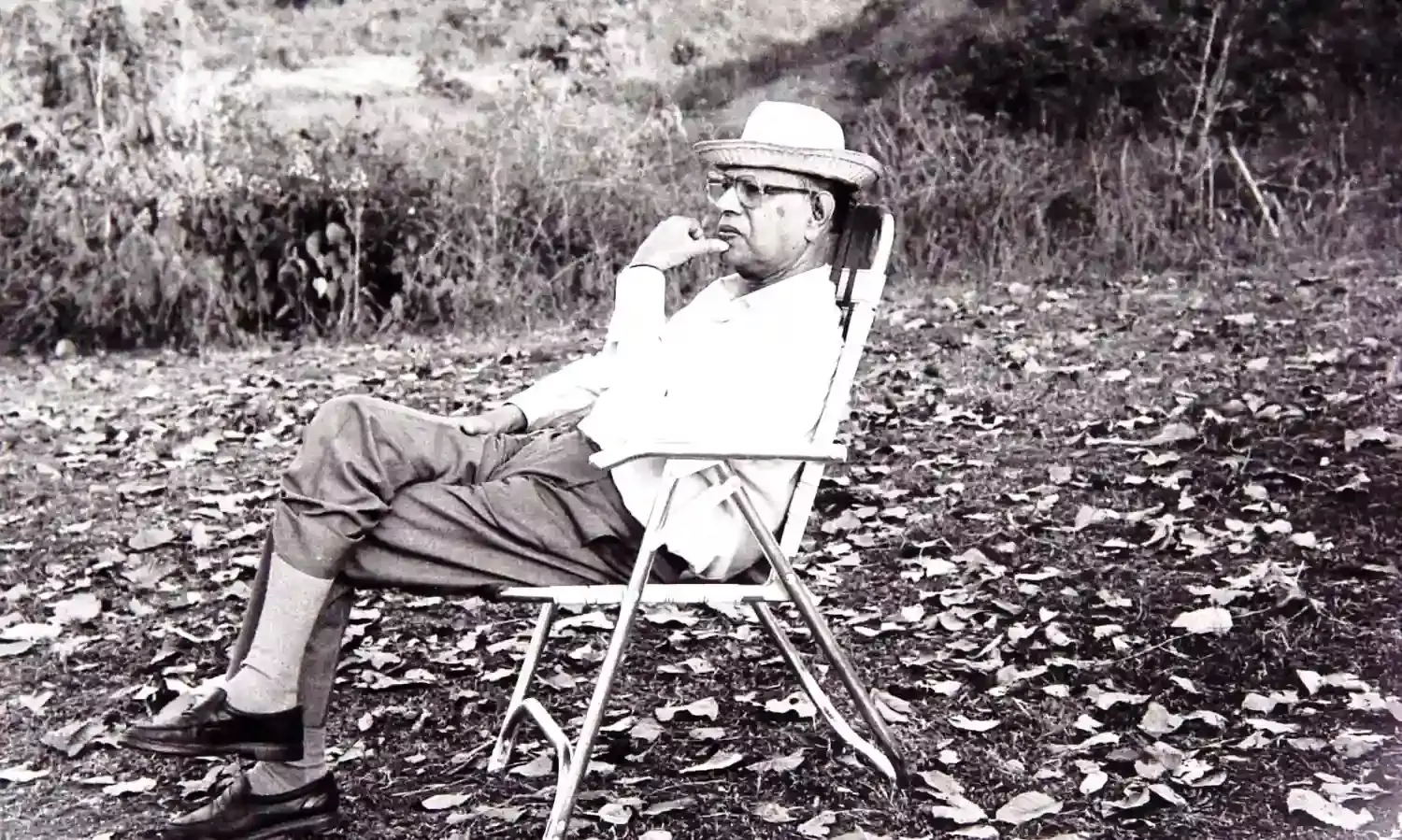

Tapan Sinha, one of the most memorable filmmakers in Bengal, can be justifiably considered to be the most commercially successful one. He, later in his career, also scored the music for his films. Sinha evolved from being a sound engineer trained in London, to a full-fledged filmmaker whose creativity spans around four decades in making meaningful and significant films.

Though he was dedicated to Bengal and to Bengali cinema, he often ventured into Hindi films, both for the big screen and for television. There too, he gave us sterling films for which he was bestowed the National Award.

These include ‘Ek Doctor Ki Maut’ and the telefilm ‘Admi Aur Aurat’. He also made ‘Aaj Ka Robinhood’ which is about preserving the environment, and ‘Safed Haathi’ for children which was a big hit.

His swan song was, ‘Shatabdi Ki Kanya’ which he could not finish. It was an anthology of ten short stories on the evolution of women over the past century. Shabana Azmi, Deepa Sahi and Jaya Bachchan played the lead in some of the short stories.

One telefilm not talked or written about much is ‘Didi’, featuring Deepti Naval in the title role. It was a film adaptation of a Bengali short story titled ‘Mahanagar’ authored by Premendra Mitra. This marks 25 years of the film’s primary telecast way back in 1989.

Sinha’s films always had a social agenda running like an undercurrent in the film and not designedly underlined like it was in ‘Ek Doctor Ki Maut’ which was inspired from a true story.

‘Didi’, a telefilm with a running time of 59 minutes, is important because it looks back on how young girls were summarily discarded by their families, if they were victims of rape or molestation. They were deemed ‘ into outcasts, leaving them to their own fate which could also lead to their untimely and tragic death.

Chapala (Deepti Naval) lives with her kid brother Ratan and fisherman father (Jnanesh Mukherjee) in a small village near Calcutta. She shares a close bond with her father and little brother, and takes care of the motherless family.

In course of time, Chapala’s father gets her married to another young boatman and the two settle down to a happy married life. But Ratan, the young brother, misses his elder sister terribly. He lands up at her home without notice, all the way in a neighbouring village.

The film opens in the present showing Ratan sailing with his father to Calcutta. His father does not know that Ratan plans to look up his “Didi” who, he has heard, lives in Calcutta’s Boubazaar.

He has no clue about where his sister has disappeared to and his father brushes away his questions with a scolding saying that she will not be allowed to return even if she wants to. When he runs to her husband to enquire about his Didi, his response is as angry as that of his father. The small boy is intrigued about where his sister went missing and why his father and her husband are not looking for her.

As the boat reaches Calcutta, Ratan scoots out of the boat and goes looking for his Didi in Boubazaar. But it is his first visit to the city and he has no idea where Boubazaar is.

A child-lifter tries to talk him into going with him but Ratan runs away. He finally lands in a shady place and meets her Didi who looks very sad, but looks different and speaks differently too.

She lives in a room more comfortable and better furnished than the home he lives in but he insists that he will take her back with him to their village home. She is dressed in shimmering clothes with lots of make-up. The innocent Ratan does not understand that his Didi has become a prostitute.

Ratan does not know and will never know that Chapala, when married to her husband, was abducted by a couple of young men, taken to a boat and gang-raped. The police those days were committed, honest and dutiful and when their old father and Chapala’s husband came looking for her, they were helpful. But the minute she was found and they learnt that she had been gang-raped, both the father and the husband turned their backs and threw her out of their lives.

Chapala then finds solace in the company of the sadhu who saved her from the boat she was sailing in, unconscious and alone. But the sadhu sold her off for Rs. 1,000 to a brothel owner.

This is an interesting pointer that tells us that the police in those days were more empathetic to women in danger, while the saffron-clad, bearded sadhu turned out to be a trafficker of young women.

The film ends on a tragic note when Ratan, angry because Chapala refuses to go back with him to the village, tells her that he will never ever come back to see her again. The camera closes in on Chapala’s large eyes and sad face sporting a shimmering bindi, considered to be an ‘identity card’ for sex workers in those days.

Music, which was Tapan Sinha’s forte, is beautiful, lyrical, soft and flowing along with the river waters. One hears the lapping of the waters where Ratan and Chapala’s old father spends most of his day, sailing and catching fish.

The sound design sticks to the village sounds of chirping birds, the lapping of the river waters and the brother and sister enjoying their growing up years together. There is no harping on their poverty though one can see that they are basically surviving on the minimum.

Though this is a story narrated quite simply, with a few time leaps to the past, Sinha stays away from any kind of melodrama and this adds to the richness of the narrative.

Deepti Naval gives a marvellous performance as Chapala. It is a layered role – a young girl playing around with her small brother when she is not busy cooking or doing household chores, then a contented bride of a young man who adores her and finally, as the prostitute who has been forced into the profession because neither her father, nor her husband are ready to take her back as she is now a ‘tainted’ woman.

She is not to blame for her abduction and her gang rape and finally, her being trafficked into prostitution but it is she who becomes a sad victim incidentally, ending up Ratan as a victim too, stripped forever of the company of the Didi he loved so much and missed so dearly.

Not once does Chapala strike out at those who reduced her life to one of a sex worker. Nor does she bear any anger against her husband and her father who have socially boycotted her forever.

She accepts all this quietly as her destiny which cannot be changed. So, Sinha as director, did not resort to any exaggerated melodrama to show Chapala as the victim of society.

Sadly, not a single good print of the film remains and the one available on YouTube is a bad one. One wishes that ‘Didi’, the original film on celluloid, as a tribute to Tapan Sinha, is resurrected from whatever state it now is.

Is a gang-raped woman shunned by her family today too? Probably yes, because the culprits are never punished and the character of the police force has changed for the worse. But parents are more empathetic than they were before.