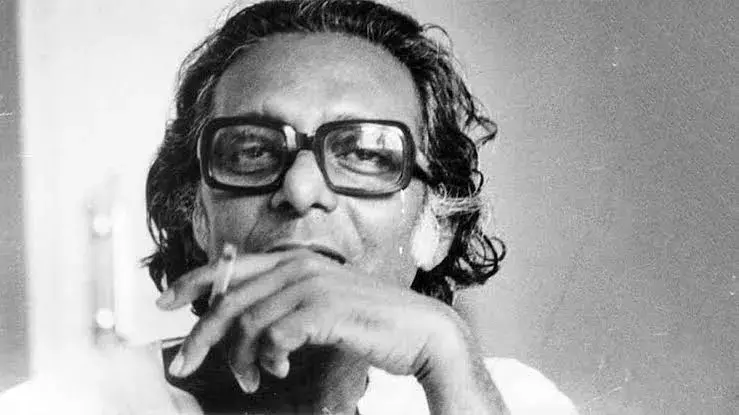

Calcutta – The City, In Five Films Of Mrinal Sen

A birthday tribute at 101

Calcutta – The City, In Five Films Of Mrinal SenMrinal Sen represents an era that survives and reflects itself through him, the lone ranger in a track now filled with other people, other cinemas. His alacrity and his nervous energy took everyone by surprise. He spiked his answers with the right dose of barbed smiles and caustic one-liners and filled them with wonderful anecdotes.

He recalled how, when he went to Bangladesh to prepare for his last film ‘Amar Bhubon’. Sen visited his home town and the place where one of his little sisters, who died, was buried. “It was a trip back to nostalgia. The tragedy had happened a long time ago. But when I reached the place, I broke down,” he reminisced.

One strong element in late Chidananda Dasgupta’s documentary on Mrinal Sen lies in capturing the ambience of Calcutta. “Whenever one tries to recall the ‘voice’ of middle-class Calcutta as captured on film, the first name that comes to mind is of Mrinal Sen. His films offer a microcosm of middle-class Bengali life in Calcutta, their problems, their hypocrisies, their pain and sorrow, their class struggle.

“So I, my chief assistant Aniruddha Dhar and my cinematographer Shirsa Ray wandered around the streets of Calcutta, took interior shots of the Town Hall, and some shots from inside a tramcar, traversing through streets frequented in the past by Mrinal himself who led many an adda with his friends of yore” informed the late Dasgupta. The film carries archival clips from some of Sen’s films.

Mrinal Sen first came to the city from his home in Faridpur in Bangladesh in 1940. He was just 17 at the time and in a documented interview he said, “I fell in love with the city the minute I came here. In Faridpur, I grew up in a closed community where everyone knew everyone else. In Calcutta, it was as if I was thrown into a huge mass of unending crowds which practically swallowed me up and I became an anonymous entity in that mass where no one knew me and yet I felt a strange thrill in belonging to that crowd.”

His films shot in Calcutta either in a house or a small flat or right across the city are memorable because singly or together, they build up a city and its surroundings in a way that raises socio-political questions on class, caste and gender with great subtlety. Among the films shot in Calcutta and located within Calcutta include, ‘Interview, Ekdin Pratidin, Kharij, Calcutta ’71, Ek Din Achanak, Padatik, Antareen, Akash Kusum’, and more.

‘Interview’ (1971) can be described as a political satire on the colonial compulsions the British regime left behind even in independent India. The film is rooted in a ramshackle, dilapidated little flat in the heart of Kolkata where the hero, Ranjit Mullick (which is also the name of the actor) lives with his widowed mother and separated sister who works in the milk booth when milk, in bottles, was not delivered at home.

The setting of the home spells out the extremely wanting situation of this family though they are together through a bond of love burdened however, by the financial pressures. The young man is desperately looking for a job though he is educated.

Finally, he is called for an interview but the condition is that he must wear a three-piece suit. Why? No one knows. The camera follows Ranjit Mullick through the wide roads, narrow lanes, tram cars, narrow staircases of Calcutta as it was in 1971, searching for a suit when he has no clue how to wear a tie!

Sen takes a long time as mother, son and sister go through wads and wads of receipts looking for the right receipt to fetch the suit sent for washing to the laundry. He does this deliberately to offer us a close glimpse into how life is lived among the less-than-affluent class of cultured Bengalis forced to toe the line.

‘Ekdin Pratidin’, based on a story by Amalendu Chakravarty entitled Abirata Chenamukh (Known faces, endlessly) describes the happenings of a day and night in a low-middle-class complex of flats where everyone knows everyone else and there is hardly any privacy. In one of these flats, Chinu, a daughter who also happens to be the sole earning member of the family, fails to return home.

Sen places his characters within a definite architectural and situational setting that establishes their socio-economic status at once. The film opens on a shot of a rickshaw moving into the scene from one end of a narrow lane, as the camera pans to show a festoon of saris hung up to dry in the courtyard, with young boys playing football within the narrow lane.

One of the boys, Poltu, is badly hurt at play and is taken to the local clinic for medicines and a dressing. Later, we learn that Poltu is Chinu's youngest brother.

Sen's command over cinema as a social comment and cinema as an art form comes across well because in ‘Ek Din Pratidin’, he crafts and styles his statement by keeping the protagonist, Chinu, absent from the cinematographic space of the screen. In fact, her very absence makes the statement more intense and stronger than it would have been with her presence.

‘Akash Kusum’ is the story of an irrepressible, incorrigible dreamer who does not bother about checking out whether his dreams are capable of being transformed to reality but goes on dreaming endlessly. Ajoy Sarkar is the protagonist who keeps building castles in the air which leads him to create a completely fake life without realising that the consequences will hit in the most, but by then, it is too late.

Like most films by Mrinal Sen, ‘Akaash Kusum’ (Up in the Clouds) which roughly translates as “castles in the air” this 1965 film also reflects the changing socio-political scenario of the city where next to the unambitious, irresponsible, handsome young Ajoy we also meet the handsome, college friend (Subhendu Chatterjee) who holds an upmarket job, lives in a spacious apartment in a multi-storIed block and even has a man-servant who takes care of his basic needs.

Sen fleshes out the city of Calcutta beautifully as the couple in love, Ajoy and Monica, wander across the Victoria Memorial, the Calcutta Dockyard with the ships sailing by, as Monika clicks pictures of Ajoy on her expensive Canon and Ajoy does the same.

Ajoy pretending to have missed carrying his wallet at a store after promising to buy Monika a sari, or, telling Monika that his friend has ‘borrowed’ his car, or offering to make tea for the friend when he drops in at Ajoy’s office but says that there is no sugar are lovely touches to flesh out the fakery he has built up around him and finds impossible to shake off when it tends to destroy the very edifice he has unwittingly and selfishly created for himself.

‘Padatik’ shows a face of Calcutta that is the violent spirit of the Seventies, now somewhat subdued like the lull after the storm. The hero of the story, effectively realised by Dhritiman Chatterjee, is an extremist who is hiding out in an apartment of an elite lady who belongs to the glamour world of advertising.

The introspection during this space that he now has makes him realise that no leadership, no matter how radical and bold, can stand the test of time and efficacy unless questioned. Padatik means “foot soldier” a metaphorical title that suggests the unstable life of the runaway political rebel forced to hide to escape being grabbed by the police.

But what kind of “foot soldier” is he? Is he forced to keep running? Or has he chosen to keep running? The answer to this is suggested towards the end of the film which leaves the question open for the audience to draw conclusions from.

Other than the political angle, the home angle of Sumit (Dhritiman Chatterjee) reveals the slow and steady metamorphosis in the relationship between father and son. The father, a brilliant performance by the late Bijon Bhattacharya, a playwright, director and actor who was never given his due, shows how the father is disgusted with an irresponsible son who ignores his family responsibilities without any touch of guilt and involves himself in political rebellion which might land him in jail.

But in the end, he comes to terms with this son and says that he refused to sign the document that included his son’s name among the missing rebels.

The film ‘Kharij’ (The Case is Closed) opens up the possibilities of a Marxist reading even within a middle-class household in Kolkata which is so casual and careless about the welfare of a boy servant they have just hired, that their neglect leads to the death of the servant boy soon after he is placed in their employment. It throws up a classic example of the powerful exploiting the weak and the deprived, completely negligent about the health issues that might have a shocking impact on the servant boy directly as a result of their criminal negligence.

Sen draws from a Ramapada Choudhury story centred on a young, middle-class, upwardly mobile Bengali couple with a small son. ‘Kharij’ tells the story of Anjan Sen (Anjan Dutt) and Mamata Sen (Mamata Shankar), a Calcutta couple who lives with their son, Pupai (Indranil Moitra).

They hire a servant, Palan, who accidentally dies of carbon monoxide poisoning while sleeping in a windowless kitchen on an extremely cold night. The moral values of the couple and their neighbours are unveiled gradually as they worry about guilt, a police investigation and a public scandal.

The strangest and the most incredible irony of the death is that everyone in the apartment building is more concerned about the social and legal consequences of the death and not shocked as much by the death itself. The couple is trapped in a silent game of trying to place the blame on each other so much that sometimes, one begins to feel that the relationship might break under the psychological and emotional tension. But these upwardly mobile middle class families are in a class of their own who are as exploitative as the richer social strata that look down on them.

In one strange sequence, Mrinal Sen shows how Anjan is scared of the local boys, both young and unemployed, on the street about being confronted by them. Anjan, a clever man, realises the tension that grows with the interaction and invites these boys home to share a cup of tea with him.

Why? Is it because he feels guilty about Palan’s death? Or, is it because he is a bit scared of these boys who might raise questions about the death and point fingers at him and his wife?

‘Kharij’ is perhaps the most scathing comment by Mrinal Sen, the filmmaker with very clearly defined Leftist inclinations who takes up an apparently simple story and turns it, through sound – excellently handled in the film, camera and most importantly, the characters to show an equally indifferent and guilty audience how easy it is for the upwardly mobile Bengali middle class of Calcutta to shrug off all feelings of guilt.

When the father and older brother of Palan take the body to the crematorium for the final rites, the camera shows them in mid shots huddled over the body not as if they are setting fire to it but as if they are warming themselves around a campfire.